Ignatius Sancho: Writer & early Black voter

Ignatius Sancho was an 18th-century writer, composer and abolitionist. His eventful life took him from an enslaver’s ship to being one of the first Black men to vote in Britain.

Blackheath & Westminster

Around 1729–1780

Breaking down barriers

Ignatius Sancho’s extraordinary life is one of firsts. He was one of the first Black writers to have his work published. He was the first Black person to have an obituary published in a British newspaper. And he is one of the first Black people known to have voted in Britain.

Born on an enslaver’s ship carrying Africans to the Caribbean, Sancho was brought to London as a young child. When he got the chance, he escaped to freedom, educated himself and worked for the wealthy Montagu family.

Sancho’s life was not the typical experience of a Black man in London in the 18th century. He wrote, composed music, argued for the abolition of slavery, ran his own business and became part of London’s elite cultural circle.

Two years after his death, a collection of Sancho’s letters was published, making him famous.

Sancho was born into an enslaved family

Ignatius Sancho was born in the Atlantic ocean, on a ship carrying enslaved Africans to the Caribbean. He lost both of his parents before he was two.

Sancho’s enslaver took him to England. Aged two, Sancho was given to three sisters who lived in Greenwich, south London.

He was named Ignatius by a bishop in the Caribbean. The sisters added Sancho, naming him after the sidekick in the novel Don Quixote.

Working for the Montagus

Sancho was enslaved by the sisters throughout his childhood and teenage years. The sisters refused to teach Sancho to read, believing that his “ignorance” would ensure his “obedience”.

They didn’t succeed. Sancho taught himself to read and write. At some point he met John, Duke of Montagu, who lived nearby in Blackheath. The duke encouraged Sancho’s education and gave him books to read.

The duke died in 1749, when Sancho was around 20 years old. Sancho decided to escape from the three sisters. He went to the duke’s widow, Mary, for help. She hired him as her butler – a respected position.

After Mary died, Sancho was hired in another prestigious position as valet, the personal servant to George, the next Duke of Montagu.

The actor David Garrick, shown here playing Richard III, was a friend of Sancho's.

Moving up in the world

During the time he spent with the Montagu family, Sancho took advantage of his new surroundings to educate himself even more. He used the Montagus’ library and mixed with an aristocratic group.

Sancho became well known for his talents. He loved the theatre, wrote plays and tried his hand at acting – becoming friends with the famous actor David Garrick. He composed and published musical pieces. And he wrote letters and essays, some of which were published in newspapers, occasionally under the name “Africanus”. In 1768 the artist Thomas Gainsborough painted Sancho’s portrait.

Financial independence

In 1758, while still working for the duke, Sancho married Ann Osbourne, a Black woman born in the Caribbean. They had seven children together.

In his forties, illness eventually forced Sancho to retire from his job as a valet. With financial help from the duke, in 1774 Sancho and his wife opened a grocery store close to the Houses of Parliament in Westminster.

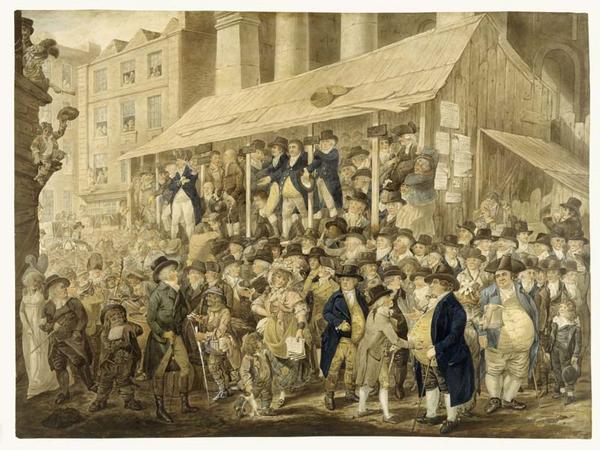

In the 18th century, men who owned their own shops were some of the few people who could vote in elections. Sancho exercised his new rights, becoming one of the first Black men known to have voted in a British parliamentary election.

“Consider slavery… how bitter a draught and how many millions are made to drink it!”

Ignatius Sancho, 1766

Sancho’s letters

Sancho died of natural causes in 1780. By that time he was fairly famous. This was helped by his friendship with Laurence Sterne, writer of the wildly successful novel Tristram Shandy.

In his life and letters, Sancho argued for the abolition of slavery. He successfully encouraged Sterne to support the cause too, writing to him in 1766: “Consider slavery – what it is – how bitter a draught and how many millions are made to drink it!”

In another letter he wrote that England's "conduct has been uniformly wicked in the East-West Indies – and even on the coast Guinea. The grand object of all English navigators, indeed of all Christian navigators, is money, money, money."

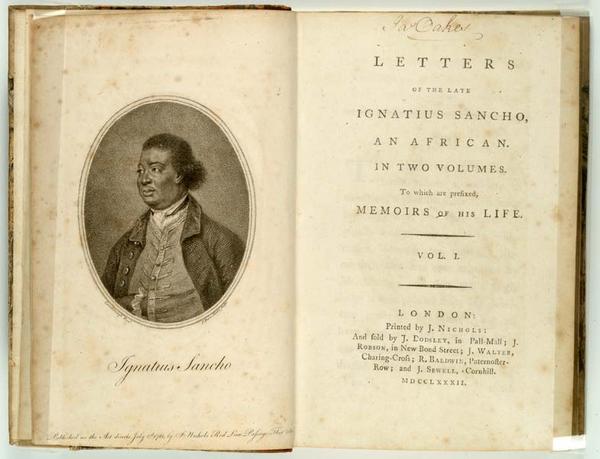

His letters were collected and published two years after his death as Letters of the Late Ignatius Sancho, an African. The book sold out in its first edition and has been republished many times. There’s a copy in our collection from 1782, complete with a portrait of Sancho on the inside cover.

How was Sancho viewed in society?

Sancho’s letters cover many subjects. But they are perhaps most unique for the insight they give us into Black people’s experience of London at this time.

By the 1780s, about 15,000 people of African heritage were living in Britain, mostly in London. There were free men and women, servants and enslaved people. But only a handful – like Mary Prince and Olaudah Equiano – wrote about their experience.

Sancho’s experience was rare. He grew up in England, became well-educated, made famous friends, and had the backing of a rich and well-connected family. Yet he still faced discrimination and harassment, which he describes in his letters.

The publisher of his letters hoped the book would show people that “an untutored African may possess abilities equal to an European”. Sancho seems to have been less hopeful. At one point in his letters, he says that “to the English… we are either foolish – or mulish – all – all without exception”.