How the Peasants’ Revolt rocked medieval London

In 1381, London was shaken by the Peasants’ Revolt. Led by Wat Tyler, rebels burned buildings, killed nobles and won an audience with the king in a famous, yet unsuccessful bid for better rights.

Blackheath, Mile End & Smithfield

11–15 June 1381

Violent rebellion comes to London

The Peasants’ Revolt began in the spring of 1381 when people in the county of Essex refused to pay a new poll tax. As spring turned to summer, the uprising against the ruling elite grew. Thousands of rebels headed for the centre of power: London.

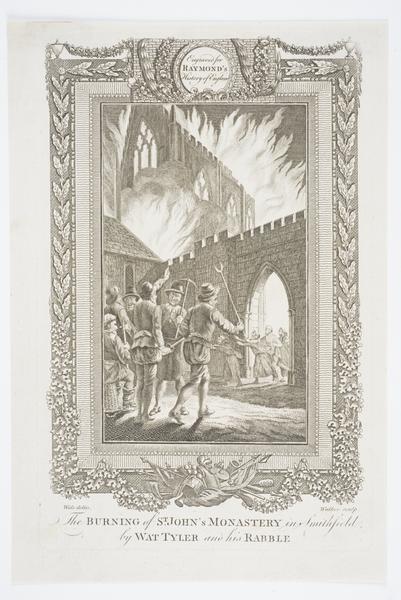

Joined by sympathetic Londoners, they rampaged through the city, destroying buildings, storming the Tower of London and killing those they blamed for the injustices of society.

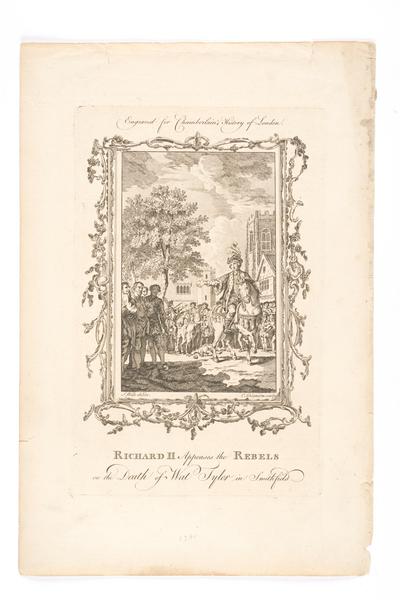

Facing a serious crisis, the 14-year-old King Richard II went to Smithfield to meet the rebel leader Wat Tyler. Tyler demanded more rights for common people, but was stabbed during the meeting and executed shortly afterwards.

The remaining rebels dispersed. They were never given the rights they were promised.

“When Adam delved and Eve span, Who was then a gentleman?”

John Ball to the rebels at Blackheath

Who were the peasants?

Despite the name, this revolt actually involved tradesmen, townspeople and ex-soldiers, as well as peasants. At the time, it was known as the Great Rising.

The vast majority of people in medieval England lived and worked on agricultural land owned by the powerful ruling elite: nobles, knights and the church. Today, these rural people are usually called ‘peasants’.

In the 1300s, some were still ‘serfs’ who were essentially owned by their lord. But others were ‘freemen’, who might instead pay rent to live on the land and could move around seeking work.

London, meanwhile, was home to roughly 40,000 people. Much of its population was made up of skilled craftspeople.

Why did peasants revolt in 1381?

By the 1380s, peasants and the other common people felt more than ever that the country was being run in an unfair way.

Wages had actually gone up after the Great Pestilence, a deadly plague which spread between 1348 and 1349. So many people died that workers could charge more for their labour.

However, this left the ruling classes unhappy. A 1351 law tried to reverse the increase in wages.

In 1377, another poll tax was introduced to fund a war in France. The poll taxes were disliked because a poor person paid the same as a rich person.

Many also believed that the government of 14-year-old King Richard II was corrupt.

A seal showing Richard II, used to stamp business and legal documents.

How did the Peasants’ Revolt start?

In 1381, people in Essex refused to pay the poll tax and attacked authorities who enforced it. This triggered violent protests that spread to Kent and beyond. Rebels executed people and destroyed buildings, legal records and the tally sticks used to record people’s debts, like the one in our collection.

Who were the leaders of the Peasants’ Revolt?

The person most associated with the Peasants’ Revolt is Wat Tyler. Little is known about his life before 1381, but he emerged as the main leader of the Kentish rebels. Starting from Canterbury, he marched to Blackheath, in south London.

Other prominent rebels included Thomas Baker, Abel Ker, Johanna Ferrour and John Ball, a preacher who used the Bible to argue that everybody was created equal. Ball is famous for summing up this idea in a speech at Blackheath by saying: “When Adam delved and Eve span, Who was then a gentleman?”

What did the rebels do when they got to London?

Tyler and his rebels arrived at Blackheath, south London, on 11 June 1381. Meanwhile, a group from Essex arrived in Mile End, east London, where they also set up camp.

On 13 June, the king, who’d been sheltering in the Tower of London, went by boat to meet the peasants at Greenwich. Seeing the rebels gathered there, he decided it was unsafe and turned back.

Angry that the king refused to meet them, the rebels rampaged through Southwark, attacking Lambeth Palace. They crossed London Bridge – probably with the support of Londoners – and entered the city.

Over the next few days, the rebels freed prisoners from Marshalsea, Fleet and Newgate prisons. They killed lawyers, government ministers and 140 Flemish merchants. A chopping block was placed at Cheapside for executions.

Among the buildings they destroyed was the Savoy Palace, which stood between the Strand and the River Thames. This was the home of John of Gaunt. He was King Richard’s uncle and the effective ruler of the country, given the king was still a teenager. Gaunt had become a much-hated figure and a symbol of government corruption.

The peasants stormed the Tower of London

On 14 June, the king met the rebels who’d gathered at Mile End. He gave in to their demands, offering them more rights.

But while the king was away from the Tower of London, rebels led by Johanna Ferrour stormed the formidable fortress. They found the Archbishop of Canterbury and treasurer Robert Hales inside. Both were beheaded.

“Brother, be of good comfort and joyful, for you shall have… forty thousand more commons than you have at present, and we shall be good comrades”

Wat Tyler to Richard II

How did the Peasants’ Revolt end?

A day later, on 15 June, the king met with Wat Tyler at Smithfield, north-west of the city. The king was joined by the mayor of London, William Walworth.

The king broadly accepted Tyler’s demands, which included an end to serfdom. But during the meeting, a fight broke out and Tyler was stabbed with a dagger similar to one in our collection. The king appealed to the rebels to leave, which they finally did.

A medieval baselard, the same type of dagger the mayor of London used to stab Wat Tyler.

How did Wat Tyler die?

After being stabbed during the meeting with the king at Smithfield, Tyler was taken to the nearby St Bartholomew’s Hospital.

He was soon captured there, and the mayor had Tyler brought back to Smithfield and executed. Go to Smithfield today and you’ll find a plaque commemorating Wat Tyler.

What was the result of the Peasants’ Revolt?

The disorder wasn’t limited to London. The revolt spread across the country, as far away as Somerset and Yorkshire.

Despite being so widespread, the revolt was unsuccessful in forcing change. Many of the rebels were executed and their bodies displayed as a warning to others.

The king didn’t keep his promises of improved rights. In November 1381, he drew a line under the event by pardoning those still accused of taking part.

There wasn’t another poll tax for 600 years, until Margaret Thatcher’s government tried it in the 1980s. That tax proved to be similarly unpopular.