How London’s alternative currencies made change

Cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin aren’t alone in sidestepping the norm. In London, a range of alternative currencies have been used over the last 500 years, often to drive economic and social change.

Since 1600

Making change

The everyday act of spending and earning money is so entwined with our lives that changing what we use as currency can reshape the way we think and act.

Londoners throughout history have used alternative currencies to try to change the city, and the world.

Some kept business flowing through a currency crisis. Others encouraged people to spend locally, as with the modern Brixton Pound. They’ve spread the word and raised funds for social crusades, like the abolition of slavery and the votes for women campaign.

They’ve even tried to change the fundamentals of finance by using time as the new unit of exchange.

Trading in trust

These tiny copper tokens – almost all less than two centimetres across – are some of the millions of trade tokens that became the currency of ordinary Londoners in the mid-17th century.

Between about 1648 and 1673, almost no small-value coins were minted by the government.

While the wealthy could use credit, everybody else needed a way to do business. So traders pressed their own farthing or half-penny tokens to give as change.

“Each token includes the names and symbols of business people”

Tokens could be spent locally, not just in the business of the person that issued them. Businesses accepted tokens issued by people they knew and trusted to honour its value.

These tokens in our collection are from Barbican Street, now Beech Street tunnel. Each token includes the names and symbols of business people – including bodice-maker James Leech, grain-seller William Milton, and chandler Thomas Cooper.

Robert Hayes cleverly used his token to advertise the new address of his Turk's Head coffee shop, after the 1666 Great Fire of London forced him to move.

The Crown produced farthings again in 1672, and banned the trade tokens. But the repeated calls to stop their use suggests they continued to circulate in the years afterwards. Locally made, reputation-backed currency served a valuable purpose in London's economy.

The Brixton Pound

A more recent example of a local currency comes from south London – the Brixton Pound. The Brixton Pound (B£) was the first urban "complementary currency" in the UK. It was meant to be used alongside pounds sterling, just as trade tokens were used alongside official currency.

The Brixton Pound was designed to encourage local spending as it could only be used with and by local businesses. Its notes featured inspirational Brixtonians past and present, including David Bowie and basketball player Luol Deng, as well as the Barrier Block on Coldharbour Lane.

A similar local currency is the Kingston pound, a digital alternative currency for the south-west London borough.

“goods were exchanged based on the number of labour hours that went into producing them”

Time is money

Some London alternative currencies chose not to copy the standard units of the financial establishment.

Instead, they create a different unit of exchange – time.

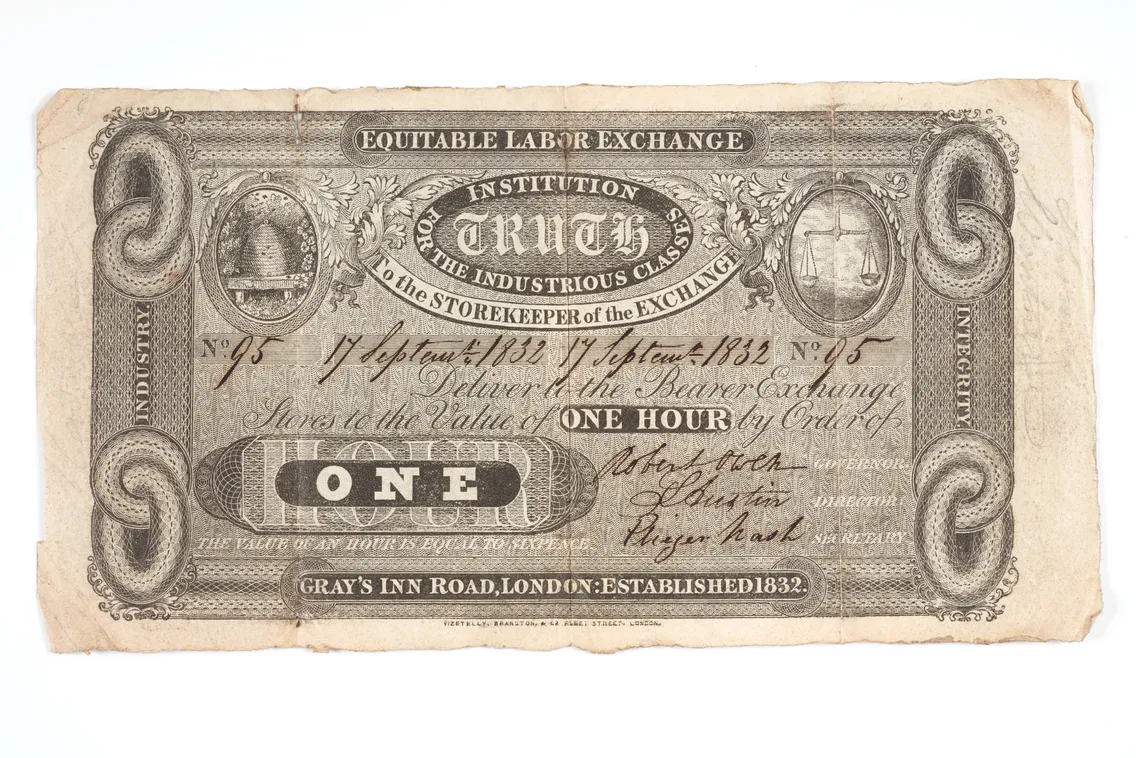

This rare note is worth one hour of somebody’s work. It came from the first Equitable Labour Exchange, set up by the socialist Robert Owen, just off Gray’s Inn Road in central London on 17 September 1832.

The principle was that goods were exchanged based on the number of labour hours that went into producing them, rather than their resale value. The exchanges proved short-lived however, as the quality of goods fell.

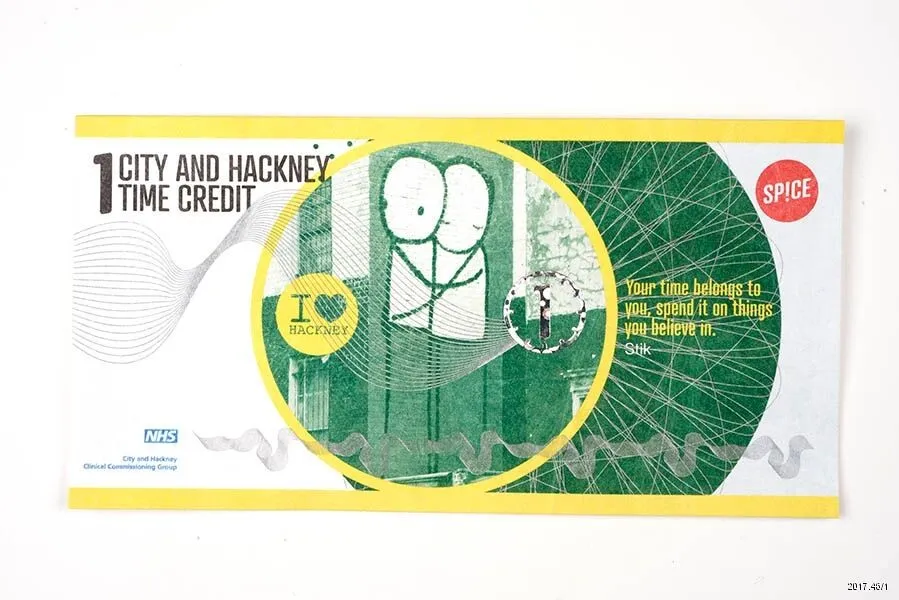

A City and Hackney Time Credit, produce by the charity Tempo.

City and Hackney Time Credit

These modern Time Credit notes come from London-based volunteering schemes, run by the charity Spice, which later changed its name to Tempo.

The idea is simple: those who volunteer for a local good cause earn credits to spend at local businesses, leisure centres, cinemas and tourist attractions.

The notes are also given away as gifts for others to spend – creating a currency that can circulate. Homeless people in Hackney and recovering addicts from Haringey are some of the many people who benefitted from this scheme.

Political currency

People seeking radical social change have embraced alternative currencies, both as a way to spread their message and to fund their movement.

There was another shortage of British coins in the 1790s. This came at a time when the French Revolution was exciting London's radicals, and many political movements produced collectible coins and tokens to spread their message of change.

The half-penny token above uses Josiah Wedgwood’s image of an enslaved African kneeling in chains and was made to raise funds for the campaign to abolish slavery.

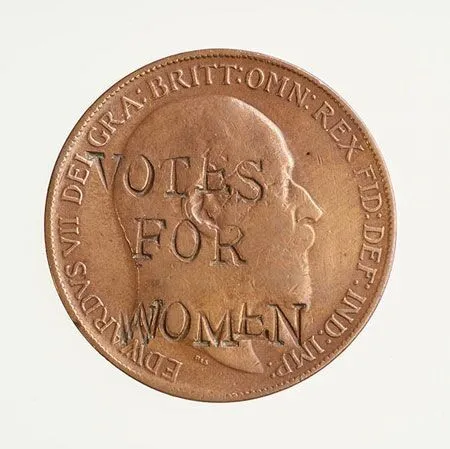

One penny coin stamped with "Votes for Women" across the profile of King Edward VII.

Other movements changed official currency rather than making their own. This 1910 one-penny coin has “Votes for Women” stamped on King Edward VII’s head.

At this time women were denied the vote. Defacing a coin was a serious criminal offence, but low value pennies were rarely recalled by the bank.

This coin could end up in the hands of any man or woman in the country – circulating its message widely. It was just one tactic used by Suffragettes to campaign for the vote.