How London shaped The Clash

Spearheading the capital’s punk rock scene in the mid-1970s, The Clash shaped their sound, style and worldview around life in their hometown of London.

1976–1986

London Calling

The Clash were one of the most iconic and influential bands to come out of London in the mid to late 1970s.

The band reflected what was going on around them in their songs. Their music drew on a broad spectrum of the sounds of the capital, including reggae, dub, jazz, rhythm and blues, rockabilly and pop. And their lyrics honed in on the political and social landscape in London and across Britain, commenting on racism, heavy-handed policing and the struggling economy.

In much of their discography, London was the lens through which they explored their musical world.

The story begins in west London squats

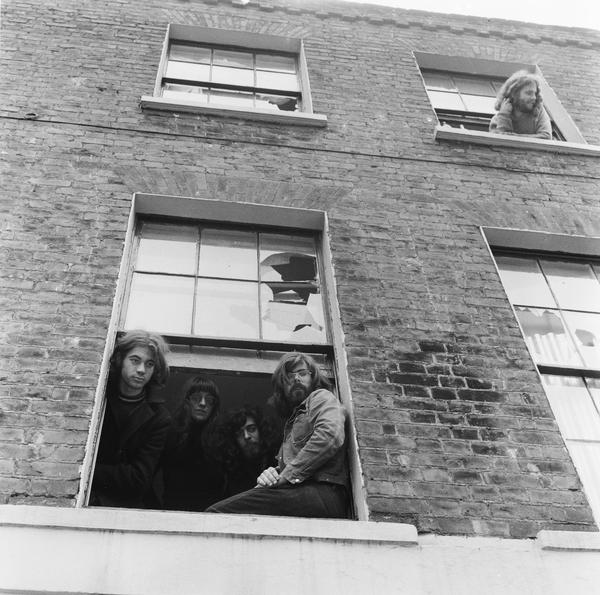

By the end of the 1970s, an estimated 30,000 people were living in reclaimed, empty properties across the city, risking being evicted and arrested.

For young Londoners like Brixton-born guitarist Mick Jones and bassist Paul Simonon, this rent-free living gave them the time and financial freedom to get stuck into music. John Graham Mellor, later known as Joe Strummer, even named his first pub rock band, the 101ers, after the squat he lived in on 101 Walterton Road, Maida Vale.

Family of squatters in Notting Hill, 1973.

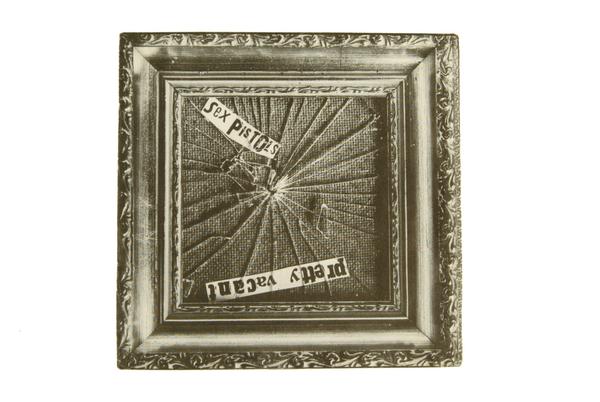

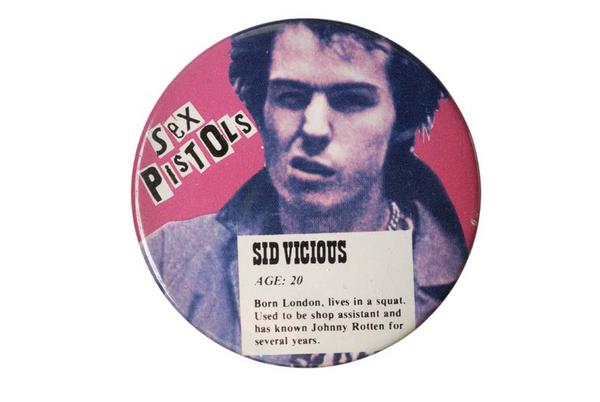

In 1976, Jones and Simonon started rehearsing a new band in a small squat near Shepherd’s Bush Green. They’d seen the Sex Pistols supporting Strummer’s 101ers at the Nashville Rooms in West Kensington in the spring of that year. In June, they asked Strummer to join their band and the foundations of The Clash were laid. Drummer Nicky ‘Topper’ Headon joined in March 1977.

“The Clash gigs were the stuff of legend”

Early punk rock pioneers

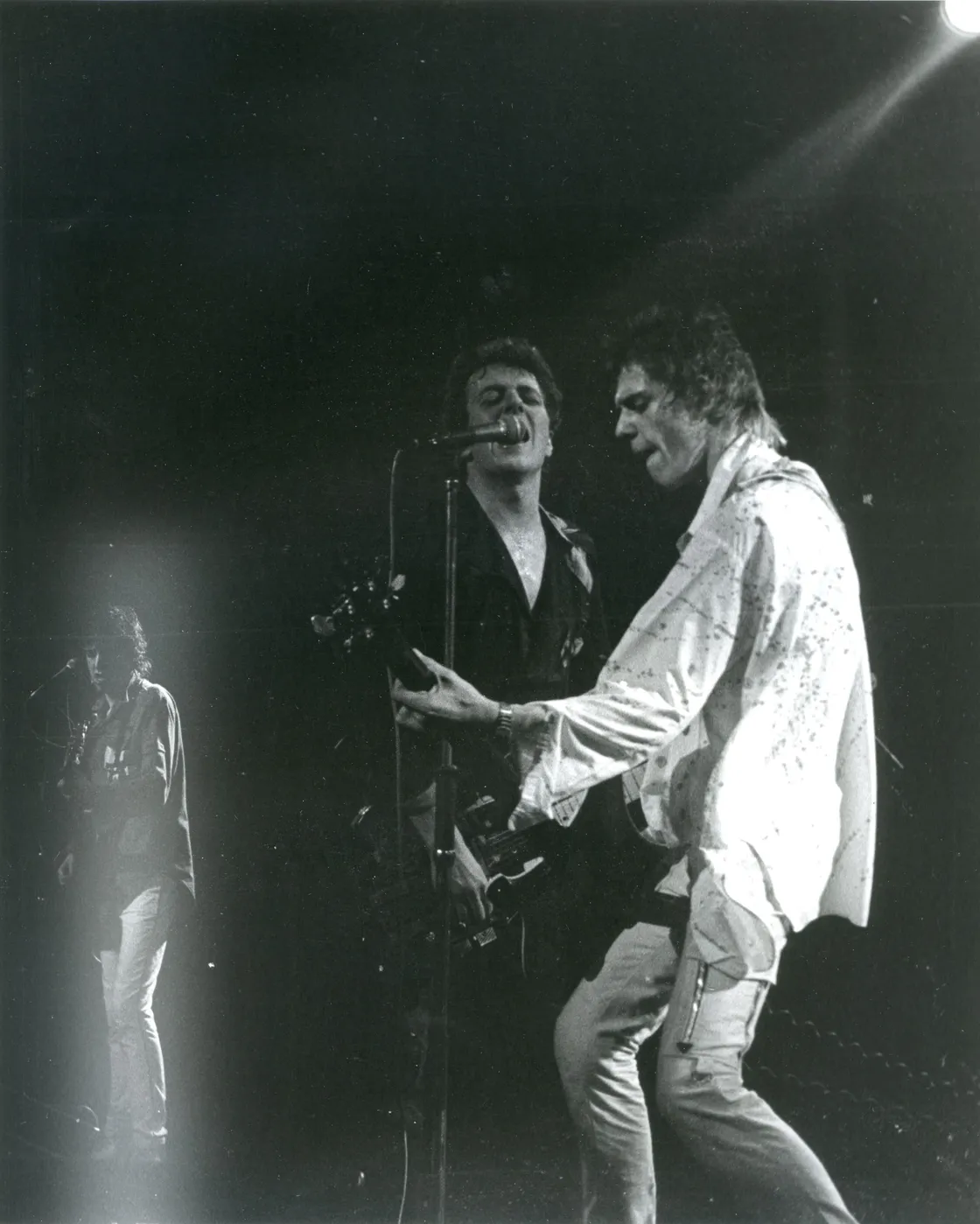

Punk’s unpolished, urgent sound and sharp, often political, messages defined the band's early music. They played at London’s key punk venues and events, pushing the genre from the unruly fringes into the mainstream. The Clash gigs were the stuff of legend, fiery and raw.

Performing at the Rainbow, north London.

In September 1976, The Clash were on the bill at Oxford Street’s 100 Club Punk Special festival. And they played the opening of the first dedicated punk venue, Covent Garden’s Roxy Club, on New Year’s Day 1977.

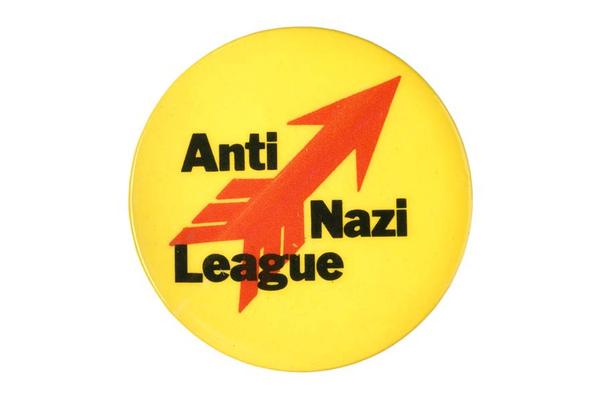

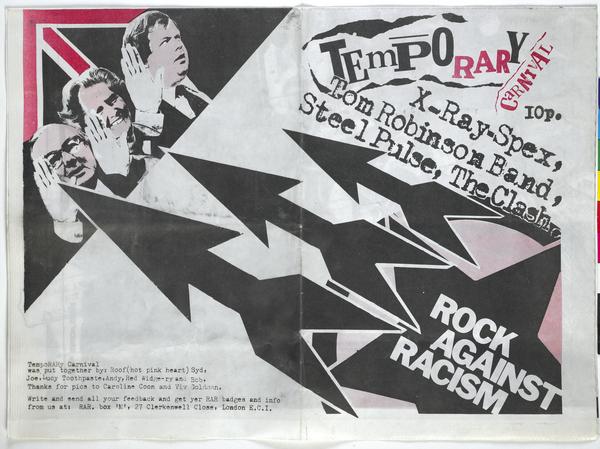

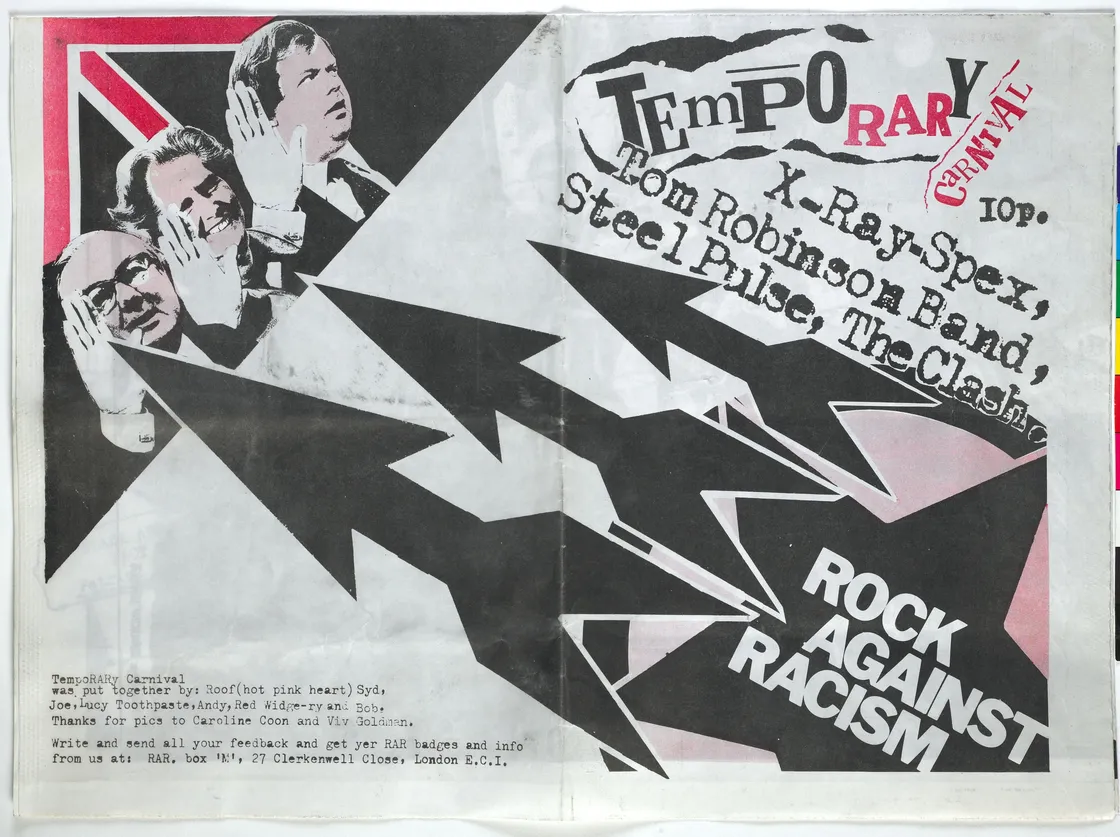

In 1978, The Clash played at a huge open-air concert in east London’s Victoria Park, organised by the Rock Against Racism movement. The ‘Temporary Carnival’ was a response to a rise in racist attacks and the resurgence of far right political party the National Front in Britain.

Programme for the Rock against Racism march and concert, sold for 10p.

Shaped by a broad spectrum of London sounds

By the end of the decade, The Clash had come to see punk as something of a musical straightjacket. They broadened their style with the music they heard live in venues and picked up in record stores across London.

They experimented with pop, jazz and the twangy guitars of 50s rockabilly and rhythm and blues, which were having a revival in the 70s.

They also looked to dub and reggae music, collaborating with Jamaican reggae legend Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry to create 1977 single Complete Control. Their 1978 track (White Man) In Hammersmith Palais also fused punk and reggae and recounts Stummer attending an all-night reggae concert at the west London music venue.

London Calling.

The influences behind ‘London Calling’

The band’s third album, London Calling, was recorded in Wessex Sound Studios in Islington in 1979 and released the same year. It’s the most explicit example of the capital’s influence on The Clash.

That year, the country stared down the barrel of a looming economic downturn. There were widespread strikes by lorry drivers, rail workers and public sector employees. And voters replaced Labour prime minister James Callaghan with the Conservative Margaret Thatcher. The album directly addresses the reality and struggles of life in London.

Over The Guns of Brixton’s rocksteady bassline, Simonon takes on lead vocals. In his lyrics, he describes the discontent in the south London area where he grew up, alluding to heavy policing and social and economic deprivation.

Clampdown, at the album’s midpoint, is a rallying cry to young people not to believe the empty promises of a failing capitalist society.

“It’s like London Calling is at the top and encompasses all the rest, like an umbrella, like the world in microcosm”

Mick Jones, 2003

And then there’s the album’s title track: the apocalyptic, anti-establishment London Calling. It uses the idea of the River Thames flooding as a way of exploring the city’s inequalities and impending sense of doom. Strummer, who lived at 31 Whistler Walk near the Thames at the time, sings: “Cause London is drowning, and I, I live by the river”.

“London Calling was the pivotal track on that album,” Jones said in 2003. “It’s like London Calling is at the top and encompasses all the rest, like an umbrella, like the world in microcosm.”