How London Pride began

Britain’s first official Pride march took place here in London in 1972. Powered by collective action and activism, Pride was one expression of a growing movement for the liberation of LGBTQ+ people in the 1970s in the UK.

Central London

1 July 1972

The power of protest

“We are gay and we are proud and we are going to enjoy ourselves.”

This statement was printed on the programme for Britain’s first Pride protest, which took place in London on 1 July 1972. A crowd of a few hundred travelled from Trafalgar Square to Hyde Park, setting the foundation for what’s now one of the biggest events of its kind worldwide.

Back in the 1970s in the UK, supporting LGBTQ+ rights would have been considered radical. Police violence, discrimination in the job market, legal injustices, bigotry and media hostility systematically oppressed LGBTQ+ people all around the country.

Pride has its roots in an international coalition of groups formed by LGBTQ+ people and their allies to demand rights and equality. The early years of Pride in the UK were linked to women’s and anti-racist liberation movements.

The Stonewall uprising

The origins of London Pride can be traced to New York, in the United States of America. On 28 June 1969, the police raided a popular gay venue called the Stonewall Inn. This sparked a week of protests against the harassment and brutality the community faced by the hands of racist police authorities. Lesbians and trans women of colour were some of the key people involved in the act of resistance which became known as the Stonewall uprising.

The Stonewall uprising wasn’t the first time that the community fought back against police brutality. But the media attention it gained changed the public discourse around LGBTQ+ activism, and it ignited widespread solidarity for LGBTQ+ rights in the US. It also led to the first ever Pride marches, which were held in New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco and Chicago on the first anniversary of the uprising.

The Gay Liberation Front

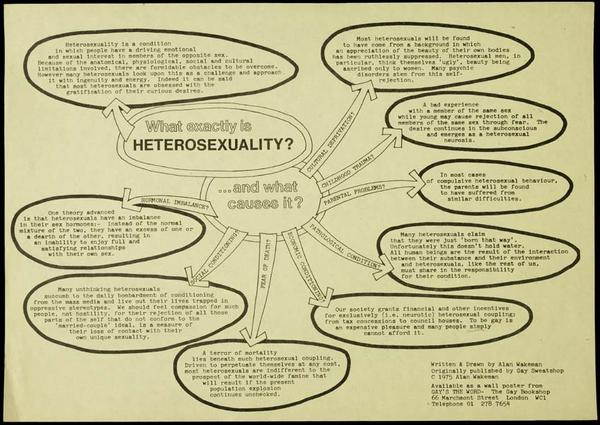

There were several groups that fought for the liberation of LGBTQ+ people in Britain in the 1970s. The Campaign for Homosexual Equality (CHE), founded in 1969, is the longest-running group campaigning for LGBTQ+ rights in the UK.

Others, such as the UK branch of the Gay Liberation Front (GLF), were founded in the aftermath of the Stonewall uprising.

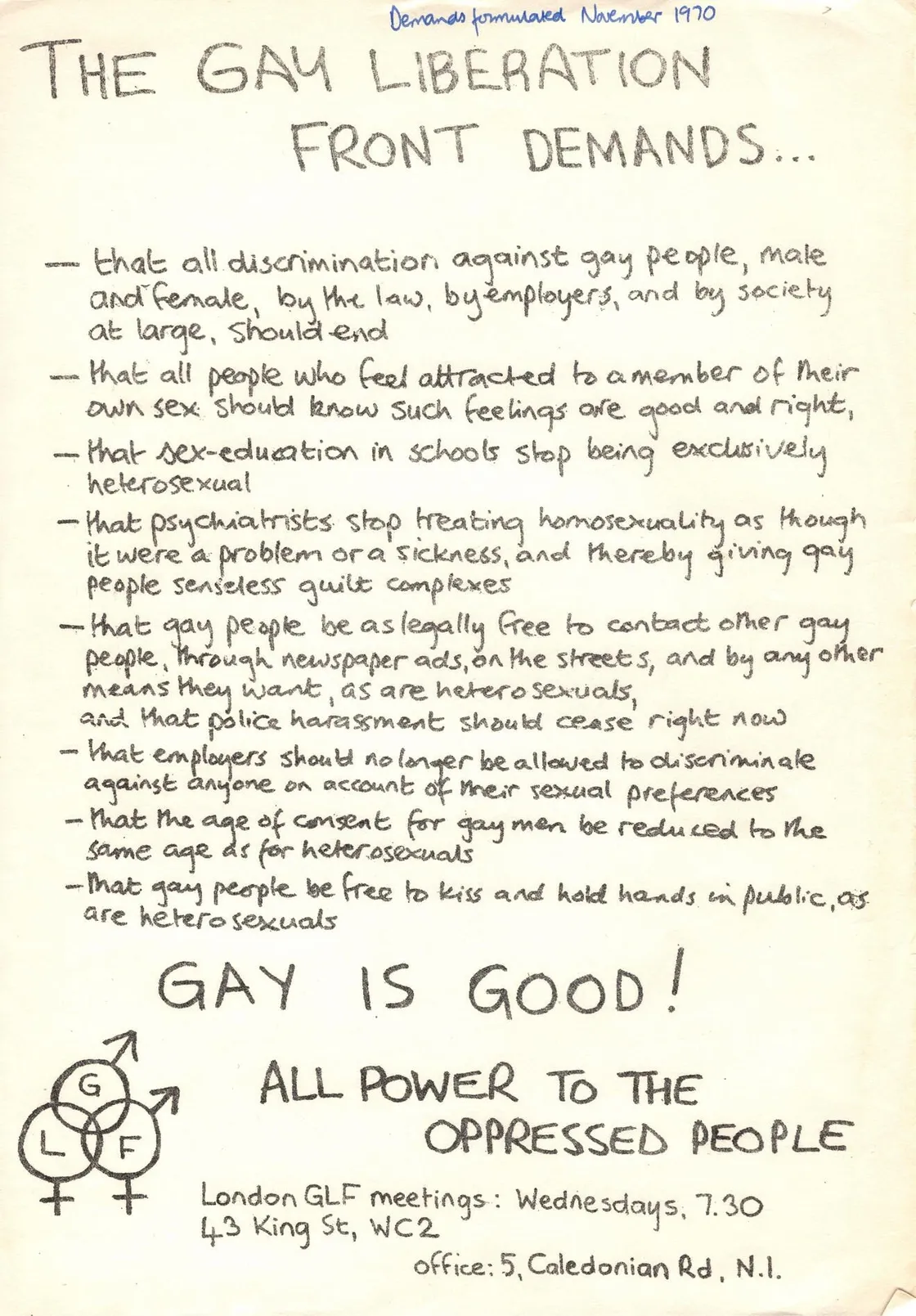

“GAY IS GOOD! ALL POWER TO THE OPPRESSED PEOPLE”

The Gay Liberation Front Demands, 1970

The British branch of the GLF was set up in 1970 at London School of Economics by Bob Mellors, a student there, and Aubrey Walter. They met at the Black Panthers’ Revolutionary Convention held the previous summer in the US. “GAY IS GOOD!” were the words that signed off the British GLF’s initial list of demands. “ALL POWER TO THE OPPRESSED PEOPLE”.

Gay Liberation Front list of demands, made in November 1970.

The GLF was only active until 1973 – but this radical organisation had a huge impact on the fight for liberation in Britain, and elsewhere in Europe.

It empowered LGBTQ+ people to be visible as political subjects calling for recognition of their rights, and to act in solidarity with other marginalised groups. A decade later, a similar approach was adopted by Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners (LGSM), which supported the National Union of Mineworkers during the year-long strike of 1984–1985.

Pride before Pride

The GLF set up meetings and workshops that brought people together to discuss key issues around LGBTQ+ oppression and activism. This time is sometimes referred to as the ‘pride before pride’.

It organised activities such as dances and ‘gay days’, gatherings held in London parks like Victoria Park and Finsbury Park that also featured games, sing-a-longs and picnics.

There were also ‘kiss-ins’, where people publicly kissed each other as a form of protest. This was a bold act. Some “homosexual acts” had been made legal in the passing of the Sexual Offences Act in 1967 – but only those done in strict privacy between adults over the age of 21. Police arrested those they saw as same-sex kissing in public for ‘breaching the peace’ or ‘gross indecency’.

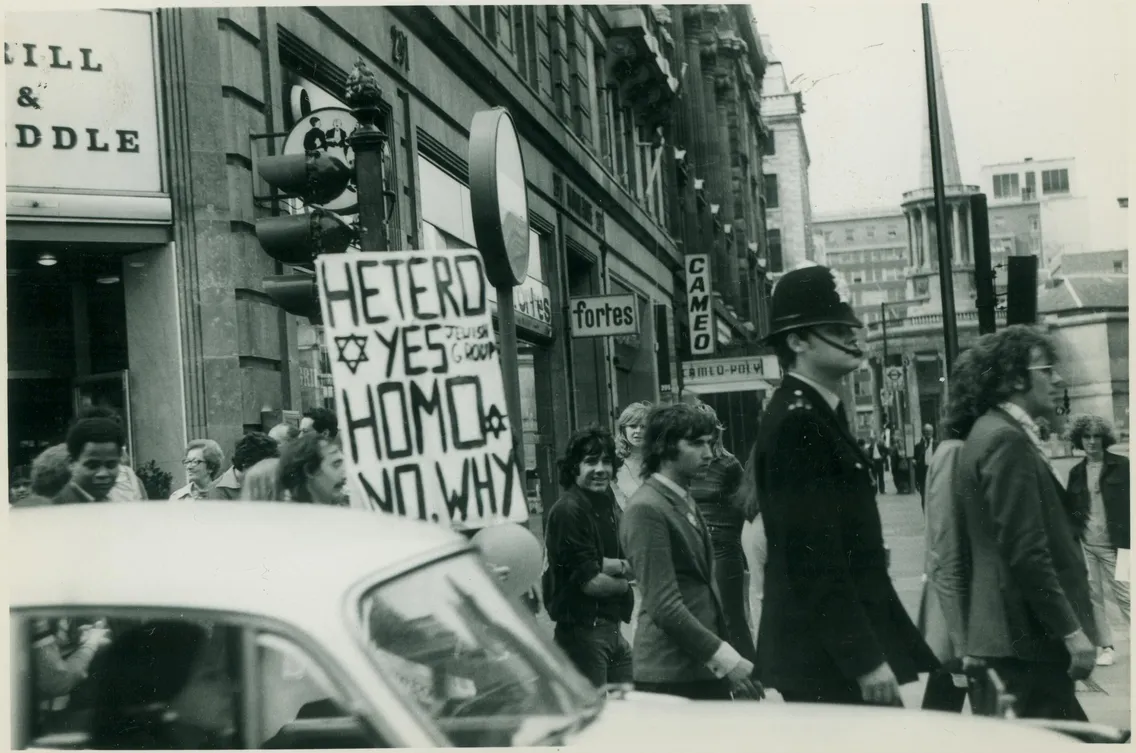

Members of the Gay Liberation Front at a demonstration in Trafalgar Square in 1972.

The GLF also organised some of the country’s first direct action events and protests. In November 1970, it held its first demonstration in Highbury Fields, Islington, against the arrest of activist Louis Eaks for ‘importuning’, behaviour police considered ‘flirtatious’.

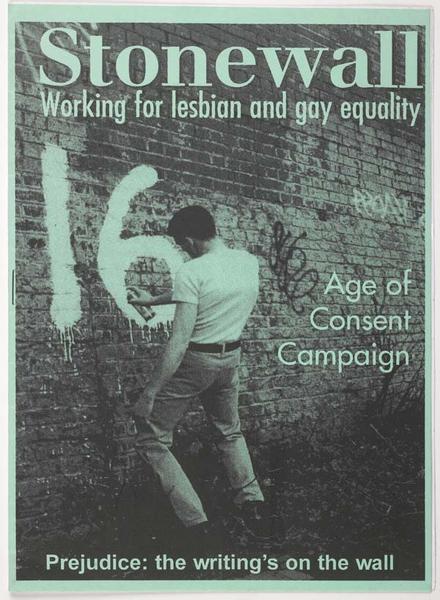

And in August 1971, the GLF Youth Group organised a march from Hyde Park to Trafalgar Square against the age of consent for gay men being set to 21. It was only in 2000 that the age of consent was lowered to 16 (same for heterosexuals) in Scotland, England and Wales. Northern Ireland had to wait until 2008.

London’s first Pride march, 1972

Britain’s first rally billed as “Gay Pride” was organised by the GLF and the CHE among others, taking place in London on 1 July 1972. This was the nearest Saturday to the anniversary of the Stonewall uprising.

An estimated 2,000 people took part in a ‘carnival parade’ of protest that snaked through central London from Trafalgar Square. Participants were encouraged to be visible and proud: “bring banners, tambourines, balloons, whistles, music, voices, and of course your best frocks,” the programme stated.

“it was a declaration of freedom, a declaration of rights”

Ted Brown

Protesters were met at Hyde Park by a heavy police presence. GLF member and activist Ted Brown remembers the defiance of the kiss-ins as an act of resistance against police violence: “it was a declaration of freedom, a declaration of rights, and we did that in front of the police almost as a challenge”.

The march was part of a week-long demonstration and ‘Gay Ins’ for London Pride, where a number of organisations fundraised and ran activities. These included talks from the Anti-Psychiatry Movement and the Gay Women Lib Group, and a concert organised by Friends of the Earth.

Pride in the 1970s and 1980s

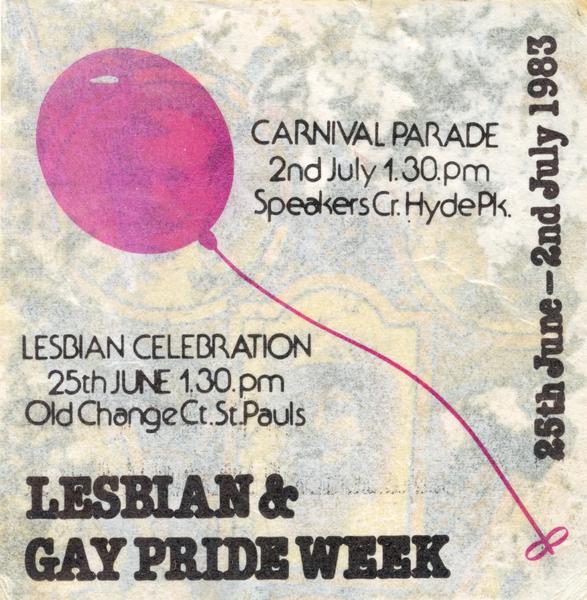

In the early years, London’s Pride was not organised by a single organisation, as it was inspired by the spirit of collective action. During the 1970s and 1980s, Pride was held on and off, with numbers attending fluctuating from one to two thousand. Since 2010, Pride marches are regularly held every year across UK largest cities.

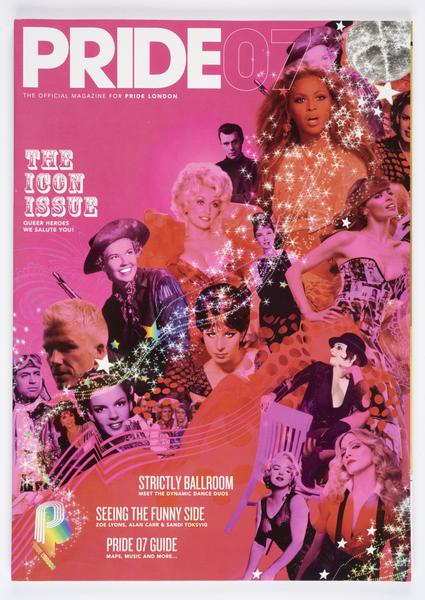

Pride events were part of a growing movement in LGBTQ+ Londoners’ fight for civil rights and recognition. Journals and magazines like Outrage and Glib were spaces for sharing ideas, events and forging a sense of community activism.

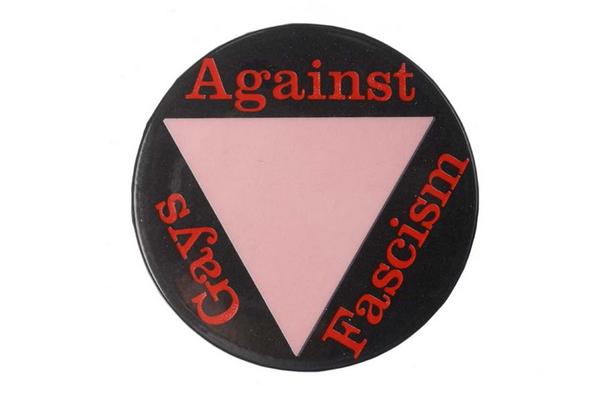

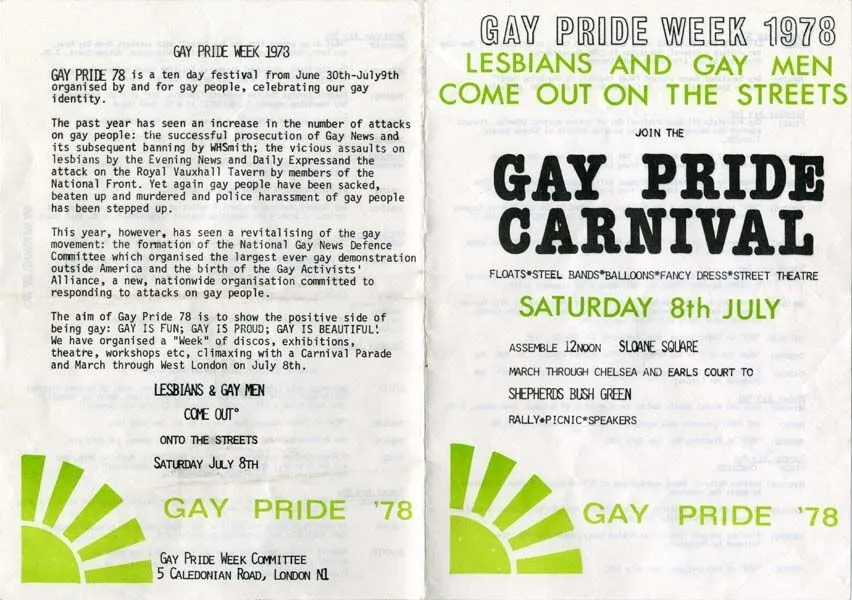

The programme for Gay Pride Week 1978 points to the “increase in the number of attacks on gay people'' over the past year. This includes the “vicious assaults on lesbians'' by the Evening News and Daily Express, and the raid on LGBTQ+ venue the Royal Vauxhall Tavern by the far-right group the National Front.

Flyer for Gay Pride Week 1978.

In its mission statement it set out to promote equality, visibility and dignity for LGBTQ+ people: “GAY IS FUN; GAY IS PROUD; GAY IS BEAUTIFUL”.

We have a number of campaign badges in our collection created in the 70s and 80s – when wearing them was a powerful statement, sometimes met with abuse or violence.

Pride in recent years

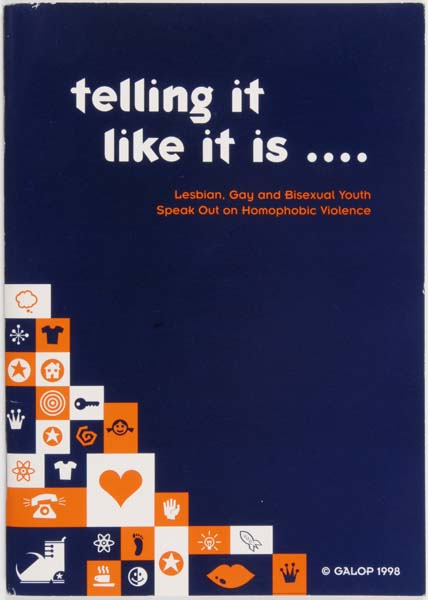

LGBTQ+ people in the UK, and trans people of colour in particular, still continue to face systemic violence, repression and hostility.

London Pride has grown to become the largest Pride event in Britain. But over the last decades, it has lost its radical platform, and many LGBTQ+ Londoners no longer feel represented by it.

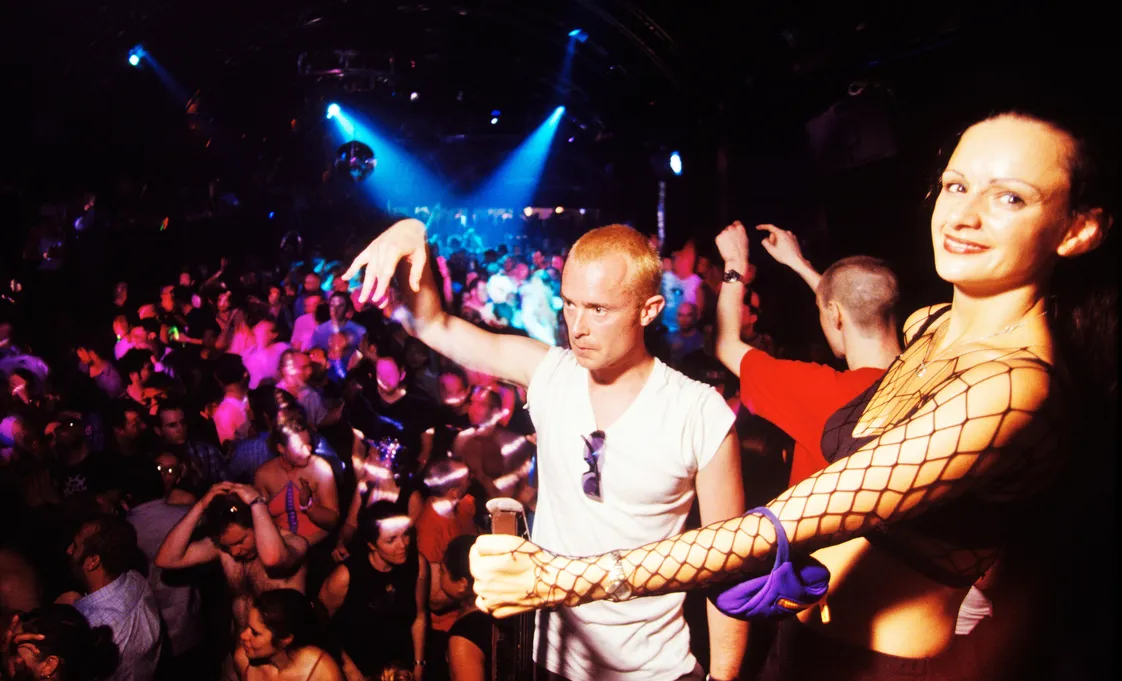

Crowds at London Pride 2022.

Pride in London, the community interest company which manages the event, has faced criticism. The LGBTQ+ charity Stonewall withdrew its support for Pride in London in 2018, citing lack of diversity. Organisers have also been criticised for corporate ‘pinkwashing’, when brands profit off their claims of LGBTQ+ allyship, but act differently in practice.

Pride in London has tried to tackle corporate pinkwashing by requiring companies sign up to a year-round LGBTQ+ inclusion programme. But in 2024, some LGBTQ+ groups have opted out of the Pride march, citing concerns over ties between some of the event sponsors and Israel’s occupation of Palestinian territory, as well as connections to arms companies supporting it.

To counter this trend, and to bring back Pride to its roots of intersectional solidarity, alternative pride events have increasingly gained momentum. In 2023, more than 25,000 people gathered in Trafalgar Square for the fifth London Trans+ Pride event. And a similar number met in Queen Elizabeth Olympic park for the 18th year of UK Black Pride.

LGBTQ+ - An acronym that refers to people who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer. The ‘+’ is to acknowledge that there are other genders and sexualities that people may identify with.

Gay – used to describe same sex relationships and sexuality, usually for men. Often used as an umbrella term for LGBTQ+ people in the past.

Intersex – an umbrella term for differences in sex traits or reproductive anatomy.

Lesbian – describes women emotionally and sexually attracted to other women.

Bisexual – describes a person emotionally and sexually attracted to both men and women.

Transgender – a person who lives (or identifies) as a member of a biological sex other than the one they were assigned at birth.

Queer – used to describe LGBTQ+ emotions, experience and sexuality. It is often used as an umbrella term for people and ideas. It was used as a term of abuse and some older LGBTQ+ people do not use it.