How Black Friday changed the Suffragette struggle

On 18 November 1910, the police responded aggressively as 300 Suffragettes tried to enter the House of Commons. Black Friday, as it became known, only made the votes for women campaign more radical.

Parliament Square, Westminster

18 November 1910

A Suffragette struggles with a police officer on Black Friday, 18 November 1910.

A dark day on the way to winning the vote

Suffragettes were the militant followers of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), a group who campaigned for women’s right to vote in elections between 1906 and 1914.

Their attempt to storm Parliament was a frustrated response to the government’s repeated refusals to grant women the vote.

The violence of the police and the crowd who gathered to watch on Black Friday sparked a change of approach. It pushed the Suffragettes towards more extreme protests, including smashing windows and burning property.

“There was not one of us who would not have gone to our death at that moment”

Annie Kenney

Why did Suffragettes march on Parliament in November 1910?

In November 1910, the votes for women campaign seemed to be on the verge of a breakthrough.

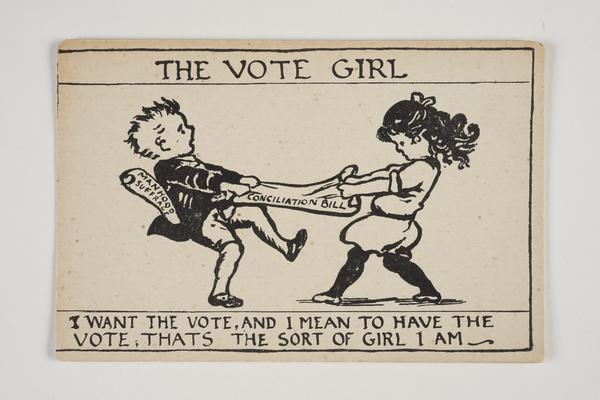

The British Parliament was considering legislation – the Conciliation Bill – that would give the vote to about a million women, mostly wealthy property-owners.

The WSPU’s leaders supported the bill, and paused their militant campaigning.

But the Liberal government had other priorities. Prime Minister Asquith called an election for December 1910, which wrecked the chances of the bill being considered.

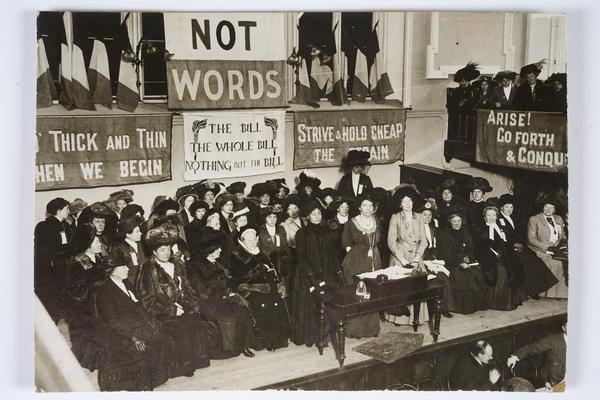

News of the election reached the WSPU as they gathered for a meeting in Westminster. Suffragette leaders, including Christabel and Emmeline Pankhurst, felt betrayed by the prime minister.

There were already plans for a peaceful march, but the 300 gathered Suffragettes now went to Parliament in a furious mood.

Suffragette Annie Kenney was on the scene: "There was a great storm-burst. All the clouds that had been gathering for weeks suddenly broke, and the downpour was terrific... There was not one of us who would not have gone to our death at that moment, had Christabel so willed it."

What happened to make it Black Friday?

After Prime Minister Asquith refused to meet members of the WSPU, the Suffragettes stayed in Parliament Square and tried to enter the House of Commons.

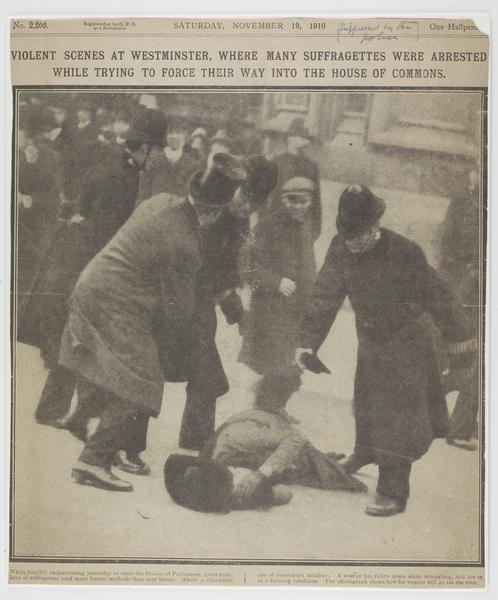

The police responded violently, physically attacking Suffragettes and throwing them into the hostile crowds of onlookers.

There were repeated sexual assaults. "Several times constables and plain-clothes men who were in the crowds passed their arms round me from the back and clutched hold of my breasts in as public a manner as possible, and men in the crowd followed their example,” described one Suffragette. “My skirt was lifted up as high as possible… [the constable] threw me into the crowd and incited the men to treat me as they wished".

May Billinghurst, a Suffragette who used a wheelchair, recalled how "... the police threw me out of the machine [wheelchair]… they took me down a side road… taking all the valves out of the wheels and pocketing them, so that I could not move".

The newspaper response

The violent scenes made the front pages of national newspapers, but the sexual assaults weren’t mentioned. Although in general journalists blamed the Suffragettes for causing the violence, the Daily Mirror noted that the police seemed to enjoy the fighting.

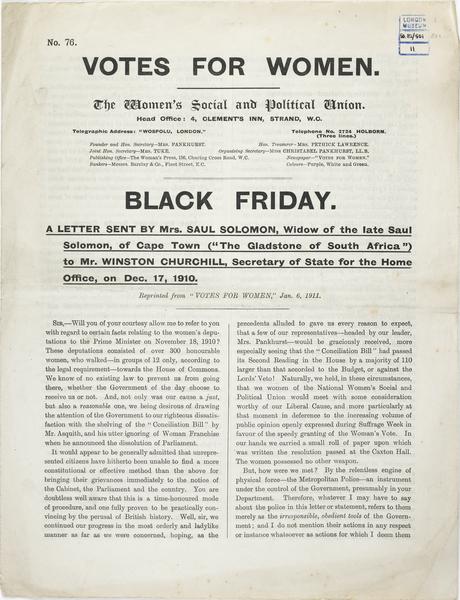

Home Secretary Winston Churchill was blamed for encouraging the police’s violent response. 119 protesters were arrested, but all were released without charge the next day, on Churchill's orders.

The police, journalists and Suffragettes all tell different stories about the violence and who caused it.

The Suffragette base at Caxton Hall in Westminster was turned into a makeshift hospital for Suffragettes with black eyes and bleeding noses. Suffragette propaganda immediately labelled this event as Black Friday, the darkest day of the campaign to date.

The front page of the Daily Mirror the day after Black Friday.

How Black Friday changed the Suffragette struggle

After Black Friday, many WSPU campaigners wouldn’t risk large marches. Instead, Suffragettes went underground to take more severe action against the government.

Many Suffragettes became bolder after their experiences. They felt betrayed by the government and were now ready to meet state violence with extreme militancy.

In November 1911, window-smashing was officially adopted as a tactic by the WSPU. Arson and attacks on public artwork were also embraced.

Suffragettes went to demonstrations armed with coshes, whips and toffee-hammers, for window-smashing and protection. A small group of WSPU militants – all trained in jujitsu – formed a bodyguard for Emmeline Pankhurst.

And Suffragette mass protests didn’t end with Black Friday. A march in November 1911 saw more confrontations with police and the smashing of many windows. 220 women were arrested.

Four Suffragettes photographed in the yard of Holloway Prison.

The long road to the vote

It was not until the Representation of the People Act of 1918 that some women over the age of 30 finally won the right to vote in British parliamentary elections.

By then, militancy had been suspended for four years, after Emmeline Pankhurst encouraged her followers to support the war effort during the First World War by taking on helpful work.

While Black Friday didn’t lead directly to women receiving the vote, their bravery on that day paved the way for women to take a more active role in society.

Edited version of blog by Alwyn Collinson, Digital Editor.