How Bazalgette built London's first super-sewer

Joseph Bazalgette is the 19th-century engineer who cleared the streets of poo by masterminding London's modern sewer system. We’re still benefiting from his genius every time we flush.

1875

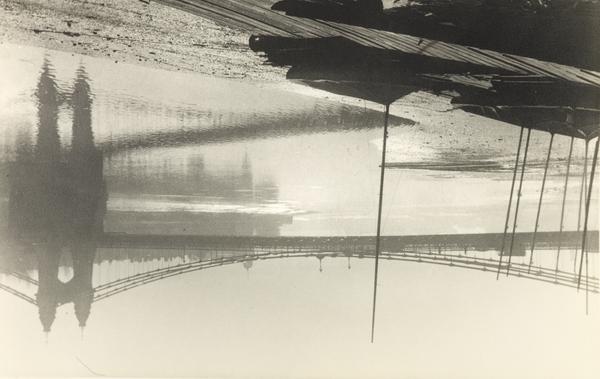

The Thames embankment being constructed between Waterloo and Blackfriars, 1865.

A filthy miracle beneath our feet

The Victorian period – when Queen Victoria sat on the throne – saw Britain become a global industrial power, with a huge empire to fund enormous engineering projects at home and abroad.

Along with the London Underground, the capital’s sewage system is undoubtedly one of the most impressive Victorian achievements.

After the Great Stink of 1858, Bazalgette was asked to solve the city’s disease-spreading sewage issues. His solution, completed in 1875, was a network of brick-lined tunnels and pumping stations so future-proof that much of it’s still used today.

Why was the sewer needed?

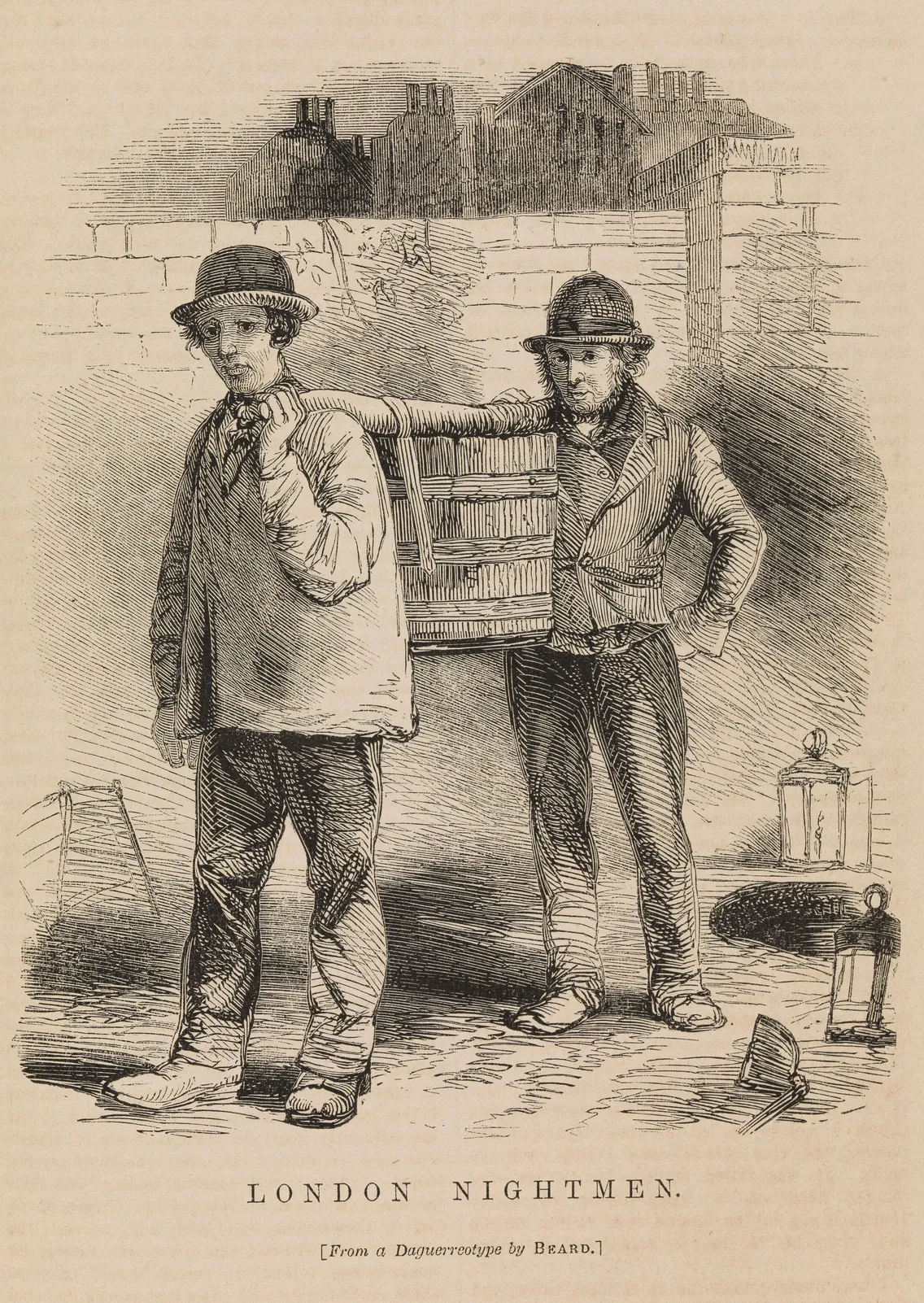

By the middle of the 19th century, the streets of London ran with human filth.

For centuries, the city depended on night-soil collectors to empty local cesspits, while waste was often thrown into the street or streams.

Old rivers like the Fleet and the Tyburn became open sewers. And most poo and wee eventually ended up in the Thames – also a source of water for drinking and washing.

The summer of 1858 saw the Great Stink overwhelm London. The hot weather exposed then baked the human and industrial waste in the Thames, creating an appalling stench which smothered the city and invaded the riverside Houses of Parliament. Water-borne diseases like cholera and typhoid fever swept through the population.

MPs reeled from the undiluted power of the stink, rushing a bill through Parliament which provided the money to construct a massive new sewer system.

What was the solution?

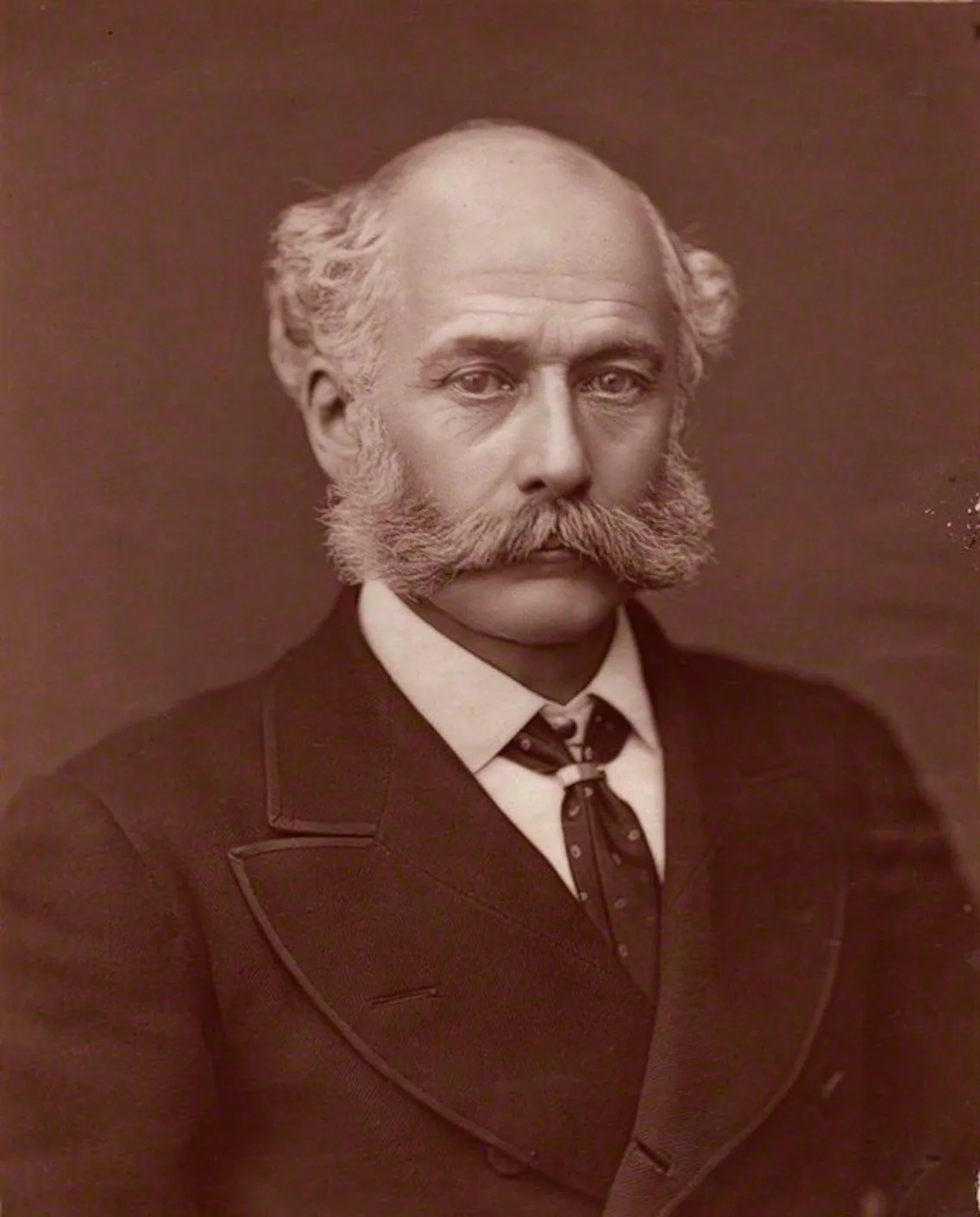

Joseph William Bazalgette was the Chief Engineer of the Metropolitan Board of Works, hired specifically to take charge of the new sewers. The cost would be enormous. Parliament initially offered £2.5 million, equal to more than £250 million today

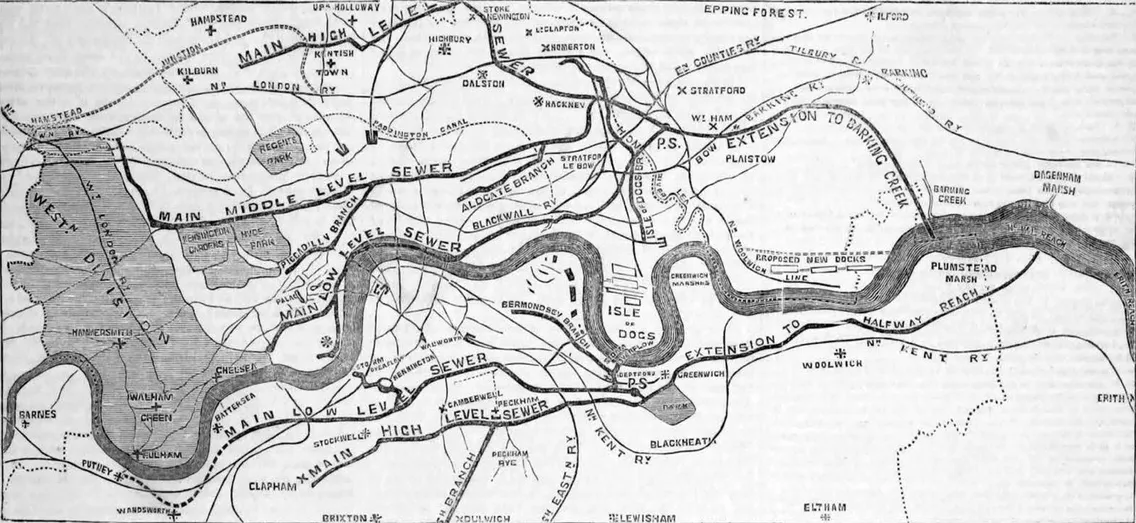

After reviewing 137 proposals, Bazalgette planned an extensive underground system of sewers, joining up the existing drains.

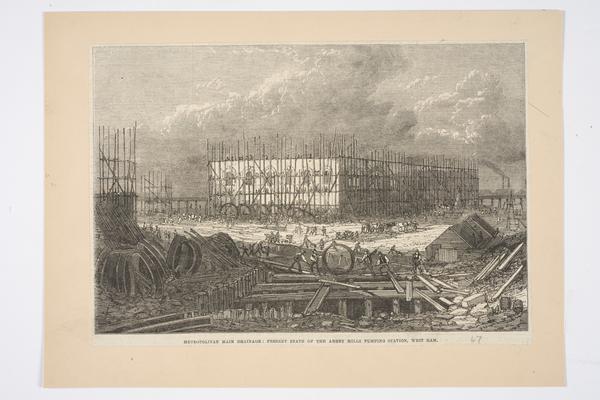

The new system funnelled waste far downstream, via pumping stations at Deptford, Crossness and Abbey Mills, dumping it east of London in the lower reaches of the Thames. At the time they were built, the pumping stations used the biggest steam engines in the world.

The plan involved building 1,100 miles of drains under London's streets, to feed into 82 miles of new brick-lined sewers, which carried waste to six "intercepting sewers".

Many of these sewers had once been natural rivers and streams like the Fleet. Now known as “lost rivers”, they were lined with brick and covered over to become huge, hidden flows of waste.

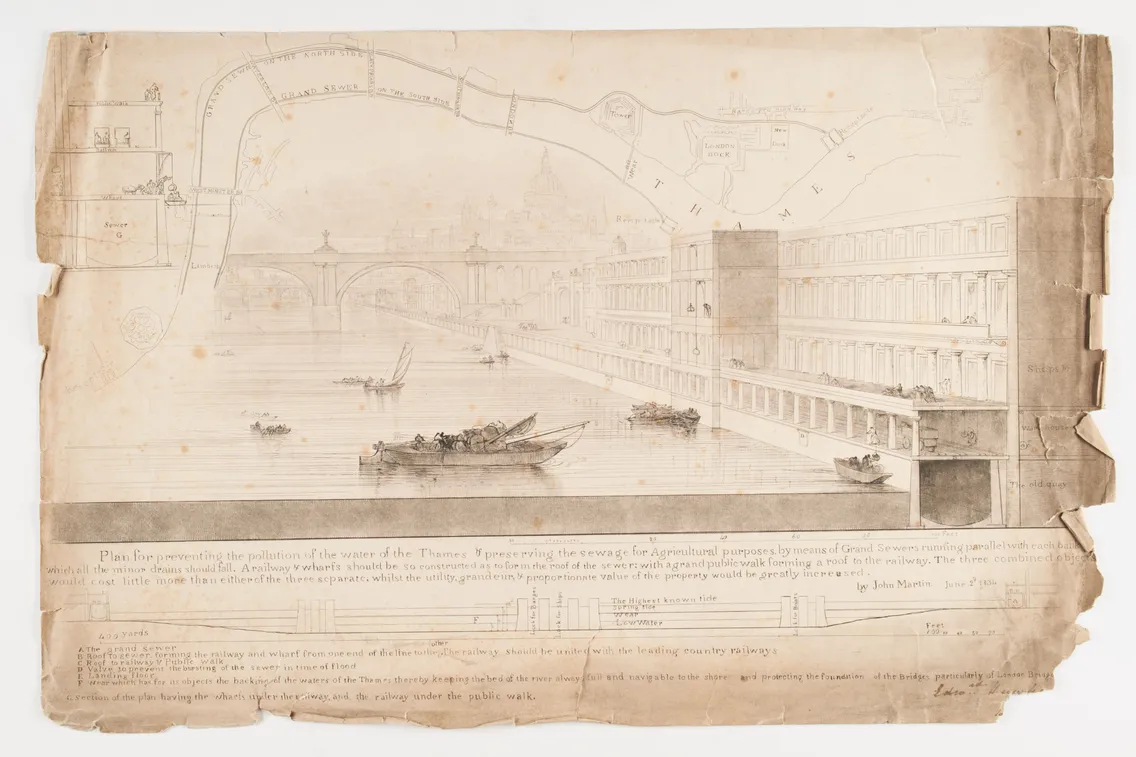

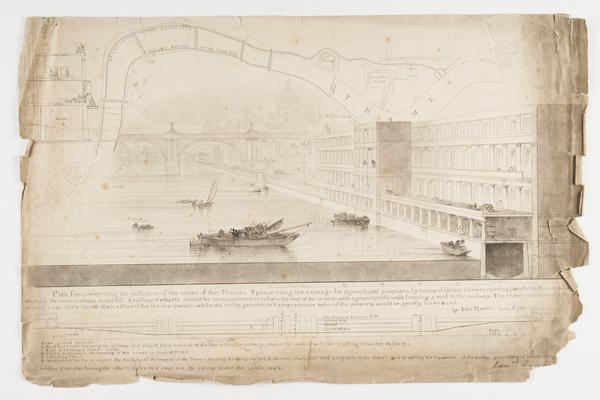

These weren't wholly original ideas: the painter John Martin had proposed something similar 20 years earlier, in 1834 – although he hoped to "preserve the sewage for agricultural purposes".

The whole project was colossal in scope, requiring 318 million bricks. Thousands of labourers were needed to dig the tunnels by hand. The demand for workers drove up bricklayers' wages by 20%.

Bazalgette insisted on using extremely strong, water-resistant Portland cement – one of the factors that has helped the Victorian sewer system survive to this day.

“Few people have done more to change the River Thames, or London, than Joseph Bazalgette”

How did the sewers change London?

Two of the intercepting sewers ran along the north and south banks of the Thames. Large new embankments were built along the river to hold the pipes – and an underground Tube line. These stone constructions narrowed the river, reclaiming about 22 acres of land.

Although officially opened in 1865, the whole project wasn’t completed until 1875. When Bazalgette died in 1891, there were 5.5 million people living, peeing and pooing in inner London, over double the number from when he first designed the sewers in the 1850s. And his sewers were still more than capable.

How important was Bazalgette?

Bazalgette didn't build or even design London's sewer system alone. But he was a tireless manager, obsessed with every detail of his work.

He inspected every plan – you can see his signature in the bottom right of this design for sewerage at the Isle of Dogs. Bazalgette personally visited every interchange to check that no waste was escaping.

Bazalgette was hands-on with the detail, signing these plans for the drainage of the Isle of Dogs himself.

He also found time to design Battersea Bridge, Albert Bridge and Putney Bridge. Few people have done more to change the River Thames, or London, than Joseph Bazalgette. But his designs certainly weren't perfect.

In 1878, the Princess Alice, a steamboat carrying day-trippers along the Thames, crashed into a coal-carrying ship and sank at Gallions Reach, near Woolwich. Around 640 people drowned in water which, just an hour before, had been filled with sewage discharged from Bazalgette’s pumping stations. Some who didn’t drown later died from swallowing the filthy water.

The tragedy drove the development of sewage treatment plants, which reduced the waste dumped into the river.

How long did Bazalgette’s sewers last?

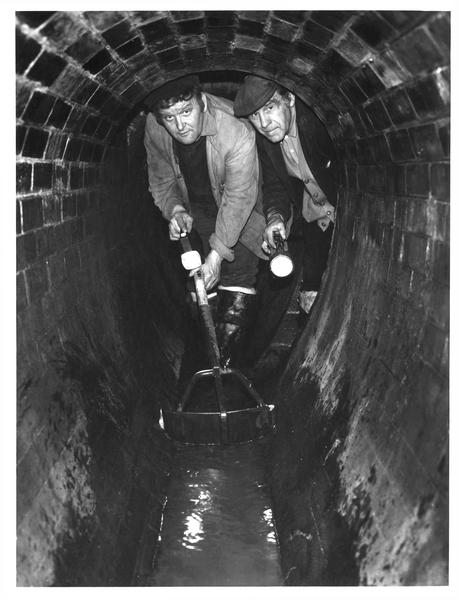

The Victorian brick-lined tunnels are still part of London's current sewer system. That’s partly because Bazalgette insisted on building tunnels far larger than were originally needed, anticipating the growth of the city.

Of course, in the dirty 21st century, we're putting new strains on Bazalgette's greatest work.

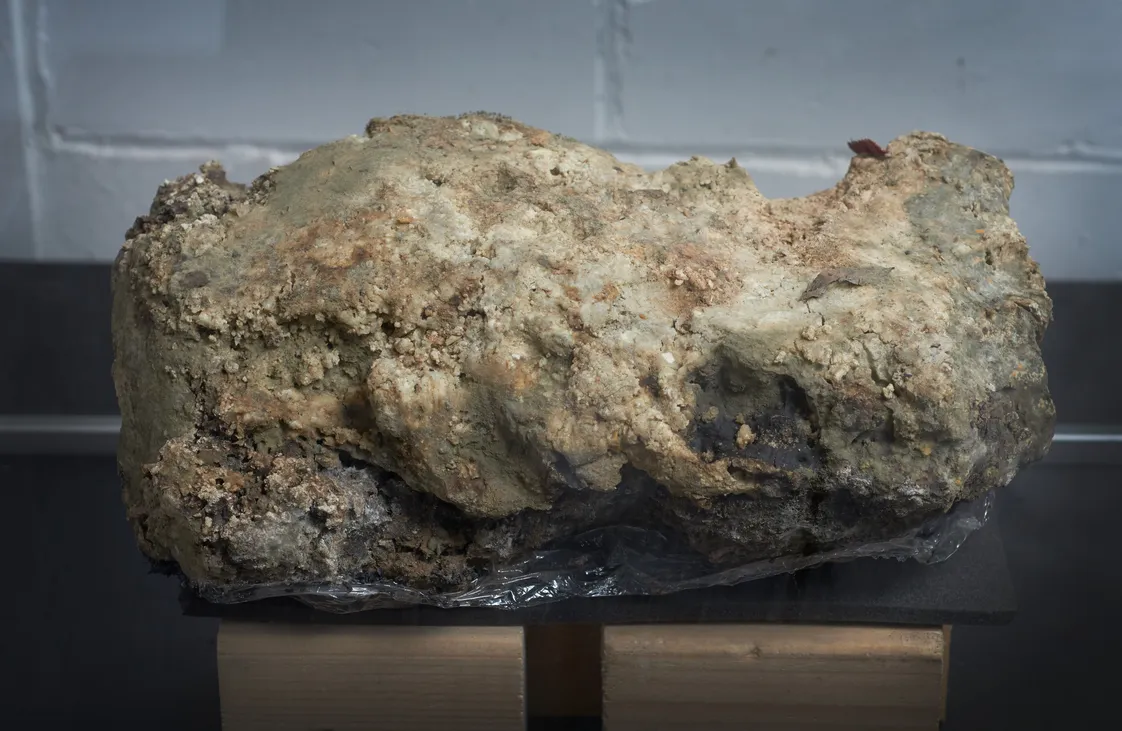

Sewers are sometimes blocked by fatbergs formed from discarded cooking oil, wet wipes, condoms and poo. The Whitechapel Fatberg, the largest ever discovered, is part of our collection.

A brand new super sewer – the Thames Tideway – has now been constructed to prevent waste being dumped into the Thames after heavy rainfall, something which previously happened regularly.

Seven metres wide, this giant tunnel runs for 25 km. Bazalgette would be proud.

Written and researched by Alwyn Collinson, Digital Editor.