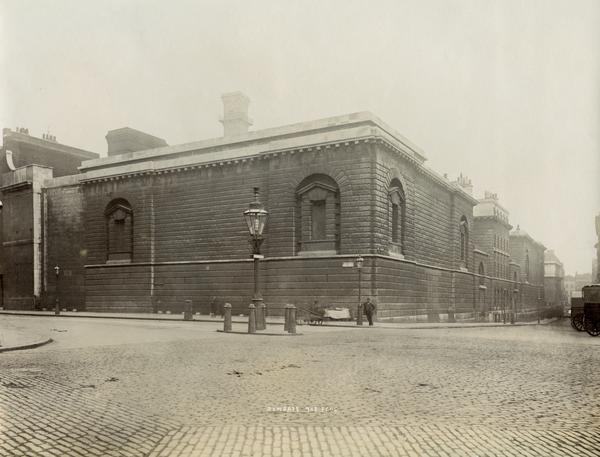

Horsemonger Lane Jail

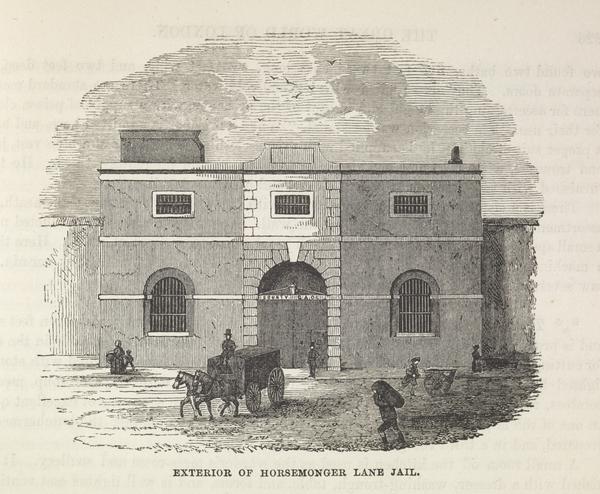

Completed in 1799 in Southwark, south London, Horsemonger Lane Jail was the site of 126 public executions.

Newington, Southwark

1799–1880

Executions were carried out on the rooftop of the Horsemonger Lane Jail gatehouse.

Death on the rooftop

London’s public executions took place all over the city, not only at infamous sites like Tyburn and Newgate Prison.

At Horsemonger Lane Jail in Newington, Southwark, hangings were carried out on the gatehouse rooftop – an elevated, highly visible stage for crowds to see the violence unfold.

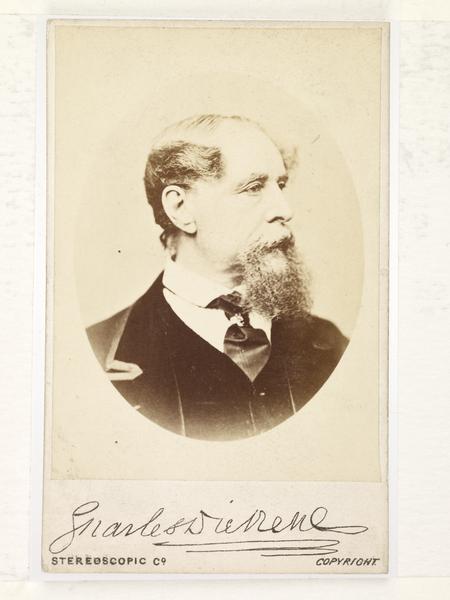

On 13 November 1849, the famous author Charles Dickens was among the crowd. He didn’t approve. And he wasn’t alone. Changing opinion led to public executions being abolished in 1868.

“a scene of horror… outside Horsemonger Lane Gaol”

Charles Dickens, letter to The Times, November 1849

County jail

Today, Southwark is a London borough south of the Thames. But until 1889, it was part of the county of Surrey.

Horsemonger Lane Jail was built to be Surrey’s new county jail. An engraved stone tablet in our collection tells us construction started on the jail in 1791.

The jail was built on land next to Horsemonger Lane, now known as Harper Road. It was three storeys tall, and surrounded a square courtyard. Three sides of the jail held criminals. The fourth was for debtors, jailed for being unable to pay their debts. The jail was designed to hold 400 prisoners but there were often more.

In 1800, the jail became Surrey’s main site for executions, a role that was previously shared by Guildford, Kingston and Kennington Common.

Hanging

Horsemonger Lane used the 'new drop' method of hanging.

When the executioner released a trapdoor beneath the feet of the condemned, they dropped, and the ropes tightened around their neck.

Horsemonger Lane’s gallows had space to hang seven people at once. They did exactly that in 1803 – twice.

One infamous execution at Horsemonger Lane in 1849 saw husband-and-wife Frederick and Maria Manning hanged together for the murder of Maria’s lover, Patrick O’ Connor.

The execution of William Cundell and John Smith

In 1812, these two men were executed at Horsemonger Lane for high treason. They were sailors who’d collaborated with their French captors during the Napoleonic Wars (1801–1815).

While some of their fellow sailors were transported to Britain’s colonies for their crimes, Cundell and Smith received the traditional traitors’ punishment.

The pair were hung, drawn and quartered – dragged across the jail yard, hanged until dead, then had their heads cut off. The attorney-general “pitied the situation of the unfortunate men” but felt the punishment would “deter others from forsaking their duty”.

The crowd and Charles Dickens

During the 19th century, London’s growing middle class wanted a more moral, more modern, more civilised society.

To them, public executions seemed to be the opposite. Spectators weren’t always sad, solemn or shocked by the violence. Many were loud, drunk and enjoyed the show.

After watching the execution of the Mannings at Horsemonger Lane in 1849, the author Charles Dickens wrote:

“I do not believe that any community can prosper where such a scene of horror as was enacted this morning outside Horsemonger Lane Gaol is permitted. The horrors of the gibbet and of the crime which brought the wretched murderers to it faded in my mind before the atrocious bearing, looks and language of the assembled spectators.”

This engraving by William Hogarth shows a large crowd gathered to watch an execution at Tyburn, which would now be close to Hyde Park.

Executions become private

In total, 126 people were publicly executed at Horsemonger Lane. After public executions were abolished in 1868, executions continued to take place there in private.

Five people were hanged in private behind its walls between 1868 and 1877. The jail was demolished in 1880.

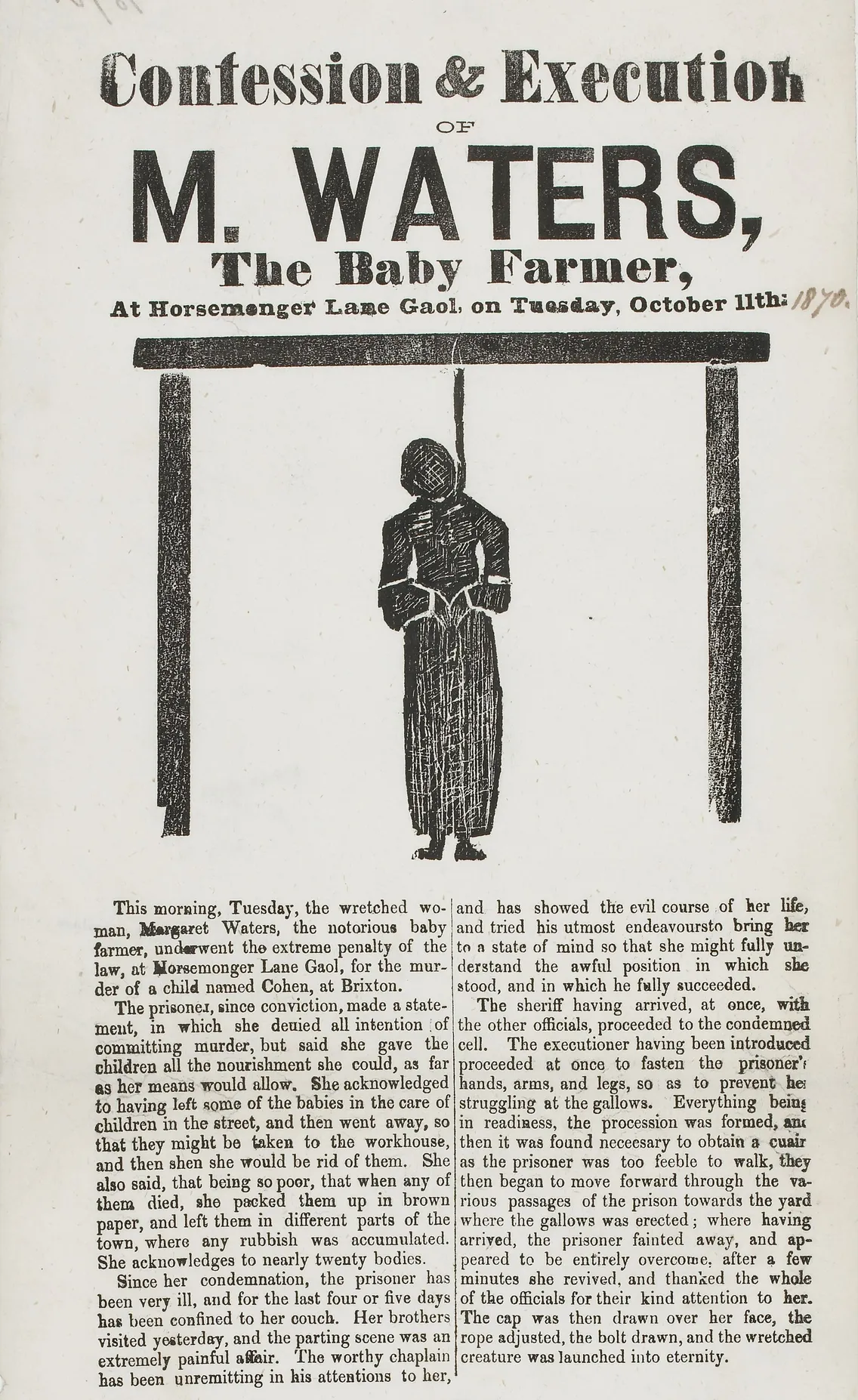

The execution of Mary Waters

On Tuesday 11 October 1870, Mary Waters was executed inside the jail for the death of a baby in her care.

This broadside labels her as a “baby farmer” – a term used for foster carers who were paid by mothers unable to look after their babies.

When police searched the home of Mary and her sister Sarah Ellis, they found nine babies, five of them dying from malnutrition and opium poisoning.

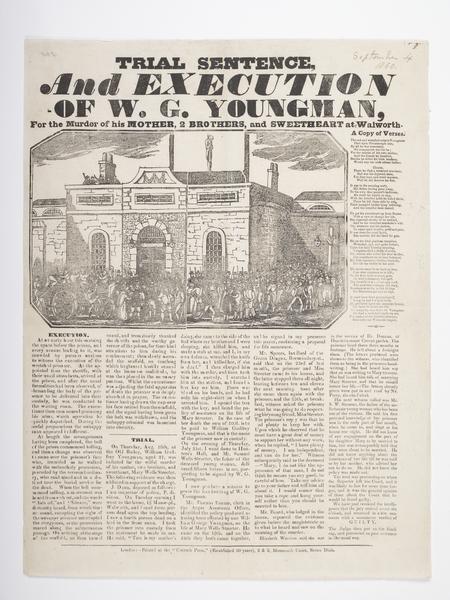

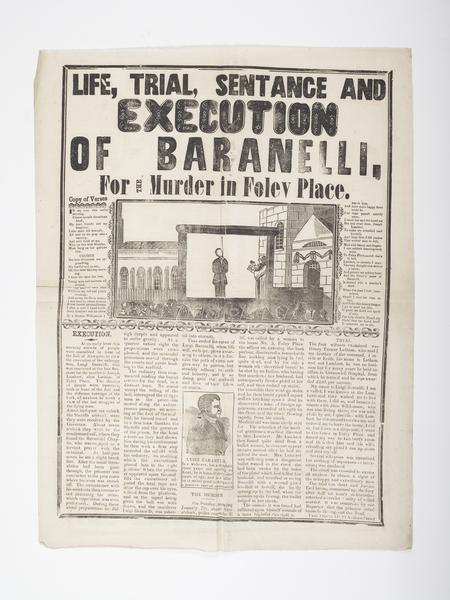

Cheap prints like these provided a popular way for Londoners to engage with executions, and a way for printers and street sellers to make money. Broadsides shared details of the case, and sometimes reported the last words of the executed. Broadsides were sold at public executions, and remained popular when executions became a private affair.