The history of Smithfield Market

Smithfield is London’s historic meat market – and an area that’s witnessed both public executions and the excitement of Bartholomew Fair. Now it’s home to London Museum.

Smithfield, central London

Since 1100

Smithfield livestock market in 1811, 50 years before it became a wholesale meat market.

Almost a thousand years of trade

Smithfield once sat just outside London’s medieval wall. Then it was “Smeeth field” – taking the Old English word for smooth to describe the flat, open area which stretched west to the River Fleet.

Smithfield was a livestock market until the 19th century. But in the 1860s, a huge and ambitious project turned it into a wholesale meat market to match London’s rapidly expanding appetite.

Housed in an innovative set of buildings, served directly by trains beneath the market floor, Smithfield was a statement of London’s status as one of the world’s great cities.

In the 21st century, many of those buildings have stood empty for decades. But today, parts of Smithfield are being carefully restored, creating a new home for our museum at one of the city’s crossroads, part of a story stretching back centuries.

Meanwhile, trade has continued at Smithfield. But in 2025, the City of London announced plans to move the market to Albert Island, in east London. A new future beckons for this historic institution.

The birth of the market

Smithfield became London’s livestock market in the medieval period. Animals reared as far away as the Midlands were brought here for sale.

In 1174, William Fitzstephen described it as “A smooth field where every Friday there is a celebrated rendezvous of fine horses to be sold… [pigs] with deep flanks, and cows and oxen of immense bulk.”

Animals were kept at Smithfield to be rested and fattened up. Once sold, they headed inside the walls to the Newgate Shambles – the city’s main slaughterhouses – or to Eastcheap, a market in the east of the city.

“It was market morning. The ground was covered, nearly ankle-deep, with filth and mire”

Charles Dickens, Oliver Twist, 1837–1839

Medieval sport and religion

The plentiful space beyond the wall attracted religious organisations to Smithfield, including St Bartholomew’s, founded in 1123, and the Charterhouse, built in 1371.

The open space was also ideal for football, archery and medieval tournaments, where knights jousted on horseback.

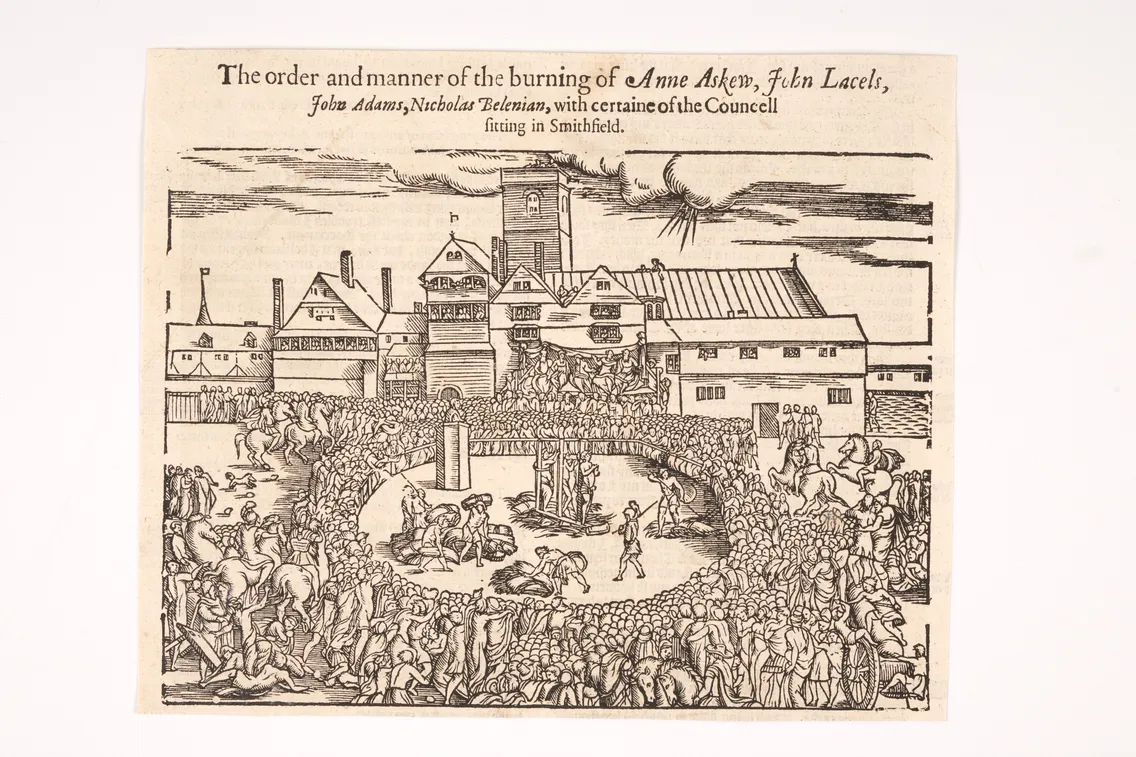

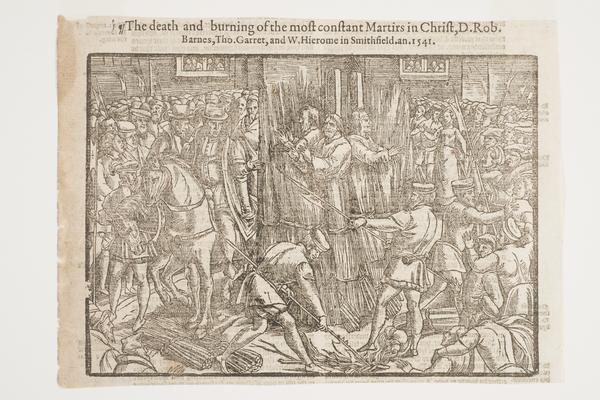

Smithfield was often used for public executions

It was here, in 1305, that Scottish rebel William Wallace was hung, drawn and quartered. Wat Tyler, leader of the failed 1381 Peasants’ Revolt, was also executed at Smithfield.

During the 16th-century reign of Queen Mary I, Protestant men and women were burnt to death at Smithfield as punishment for their religious beliefs.

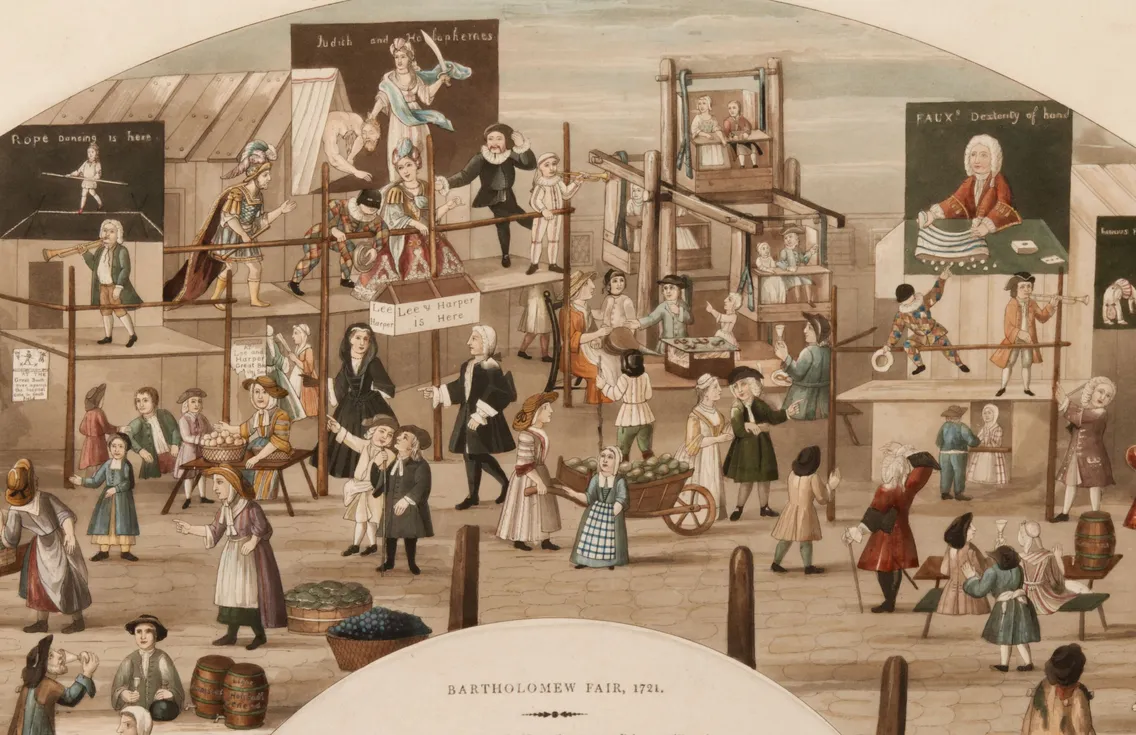

The famous Bartholomew Fair

This annual summer gathering at Smithfield ran for over 700 years. Starting in 1133 as a trade show for buyers and sellers of cloth, the food, drink and sideshows eventually became the main attraction.

By the 1600s, London’s most famous fair was pure entertainment – two weeks where crowds gathered for food, drink, puppet shows, wrestlers, a ferris wheel, dancing bears and contortionists.

Many Londoners loved it. But the chaos disturbed those who wanted a civilised city. Bartholomew Fair was shut down in 1855.

The end of the livestock market

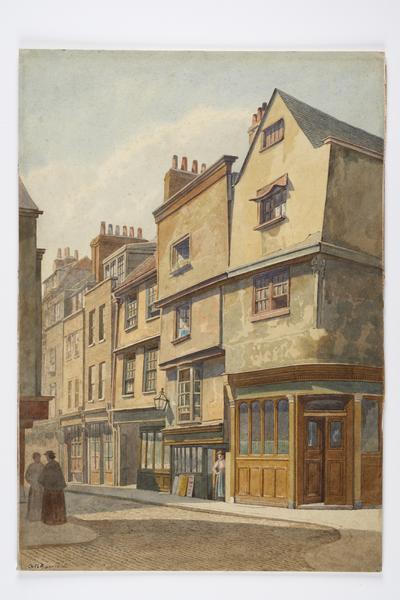

London’s continuous expansion saw the area around Smithfield become a maze of crowded streets, untouched by the 1666 Great Fire of London.

The market grew, as did the noisy procession of animals which made their way there.

In Oliver Twist, published 1837–1839, Charles Dickens captured the disorder: “It was market morning. The ground was covered, nearly ankle-deep, with filth and mire… the bleating of sheep, the grunting and squeaking of pigs… the shouts, oaths and quarrelling on all sides… rendered it a stunning and bewildering scene.”

The livestock market was closed in the 1850s. In 1855 the City of London Corporation opened a new livestock market and slaughterhouses in Islington, north London, replacing Smithfield and the Newgate Shambles.

The new covered meat market, shown here in 1870, was a spectacular, modern upgrade.

When did Smithfield’s meat market start?

Construction of a covered market at Smithfield began in 1866. From then until the 21st century, Smithfield has been a wholesale meat market, where traders process carcasses, primarily to sell to shops and restaurants.

A very modern 19th-century market

Horace Jones, who also designed Tower Bridge, was chosen as the architect of the grand new market.

His imposing and elegant complex of buildings included the Central Meat Market, General Market and Poultry Market. All were innovatively designed to help business run smoothly in the face of mountains and mountains of meat.

Smithfield adopted the latest materials and technology – a demonstration of London’s wealth and modernity.

The General Market’s extra-strong Phoenix columns held up the enormous ceiling – allowing for a large, open hall. Its roof used laminated wood rather than iron to avoid storing heat, keeping the space cool. And pioneering cold stores and refrigeration were added over time.

The General Market during renovations as London Museum prepares to move in.

Smithfield was served by trains

The market’s most revolutionary feature took advantage of London’s growing railway network.

Smithfield was connected to the north, south, east and west. Metropolitan Railway freight trains passed right underneath the market.

So the architect designed a massive basement of brick arches and iron girders to receive them. From there, the meat was lifted to the surface by hydraulic lift, or taken up the spiral ramp in the nearby rotunda.

“a tight-knit community, full of tradition, with generations of the same families working in the same place”

A world of its own

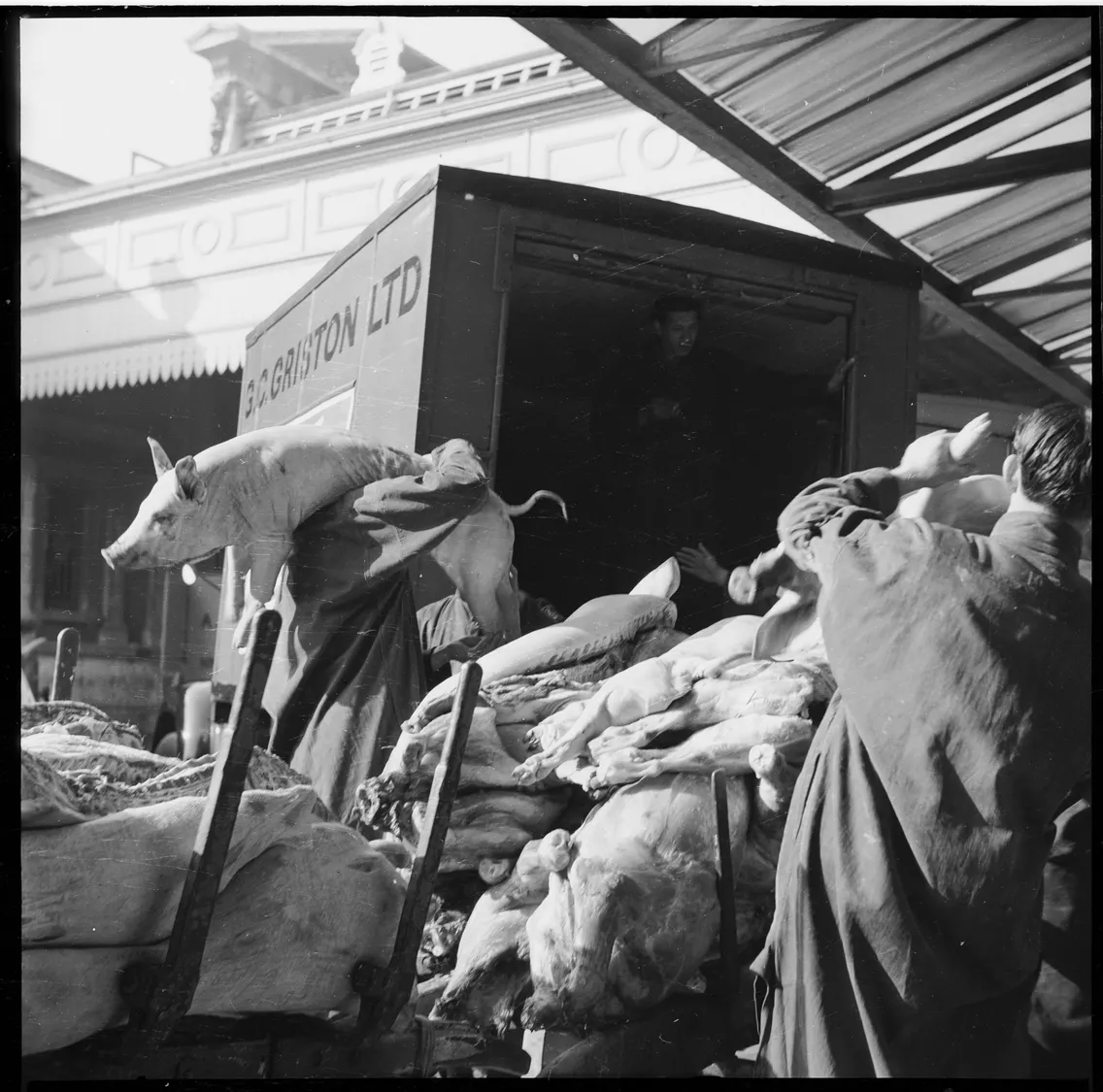

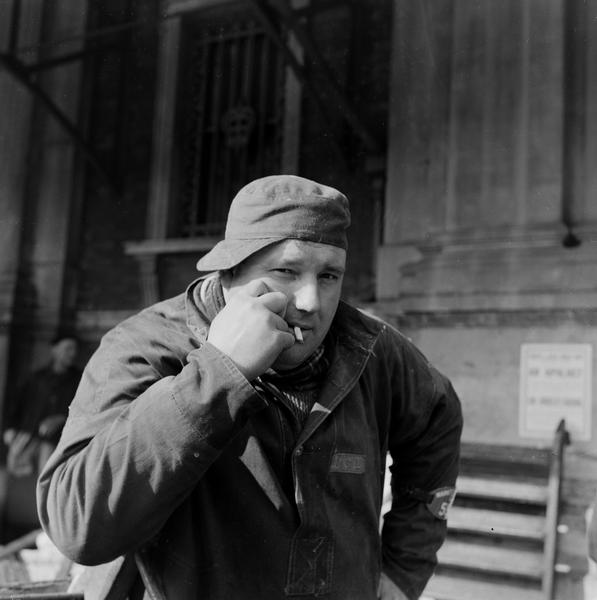

Smithfield was almost a city within a city – and one with its own hours.

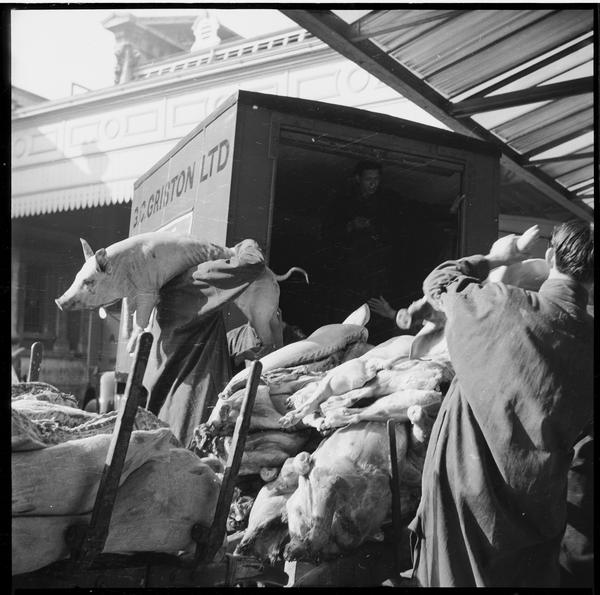

To give customers time to buy and prepare their meat for sale the same day, the market opened at night. Workers finished their shifts in the early morning. Many headed to “early houses” – pubs within the market or nearby which opened early for workers.

The market was mostly filled with men. Their work might have seemed grisly to outsiders. But it was a tight-knit community, full of tradition, with generations of the same families working in the same place.

Until 1996, the market was heavily unionised and there were strict job divisions. You might be a puller-back, a pitcher, a shunter, shopman or bummaree.

A shrinking market

By the 1880s, Smithfield was receiving enormous amounts of frozen meat from Argentina, New Zealand and Australia. It was a symbol of Britain’s global influence, with London at the centre.

But from 1945, Smithfield gradually became less busy. Meat stopped arriving through London’s docks. Britain’s trading relationships changed. And supermarkets began placing orders directly with suppliers, cutting out Smithfield’s traders.

Other London markets, like Spitalfields and Covent Garden, moved out of central London. Smithfield stayed, but reduced in size.

London Museum and the future of Smithfield

Today, the area around Smithfield is alive with culture, clubs and restaurants, connected to east and west London via nearby Farringdon Station and the new Elizabeth Line.

In 2015, the City of London Corporation invited London Museum to move into two derelict buildings on the site – Smithfield’s Victorian General Market and its 1960s Poultry Market.

With more than 800 years of history on this spot, it’s the ideal place for us to tell London’s story, in a modern museum worthy of our great city. Our new museum for London opens in 2026.

Separately, in 2025, the City of London proposed plans to relocate Smithfield market to a new site at Albert Island in east London. The island at Royal Docks would also be the new home of Billingsgate, the city's historic fish market.