London pigeons: A bird's eye view of history

There’s a good reason we have a pigeon as our icon. For over 1,000 years these birds have watched London change and grow – becoming a symbol of the city in the process.

Across London

Since 1 CE

As photographer Matt Stuart aimed his camera at people's legs in Trafalgar Square, a pigeon strutted past at just the right moment to complete the photo.

London's bird

Since their ancestors escaped Norman dovecots almost 1,000 years ago, feral pigeons have flourished in London.

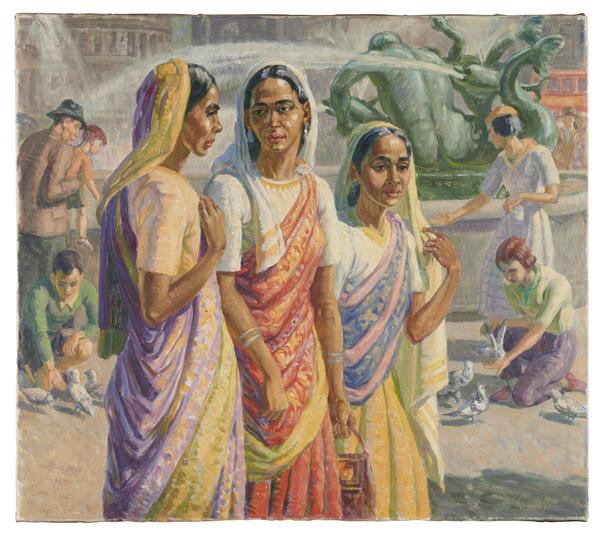

Feeding pigeons in Trafalgar Square is one of those truly iconic London scenes.

But pigeons are also treated as pests. Today, feeding is banned in Trafalgar Square and Harris hawks have been used to patrol the area.

Still, pigeons remain. Watching London as they have for centuries. At home in every alley and palace. Flying freely through the city’s grit and its glitter. Unafraid to perch on anyone’s statue.

The pigeon is a symbol which unites our city. It’s a link between past and present. And we’re proud to have it as our London Museum icon.

Harold Deardon's 1950s painting of a family feeding pigeons in Trafalgar Square.

Where do London pigeons come from?

London’s pigeons are descendants of rock doves – scientific name Columba livia – domesticated in England around the time of the Norman invasion in 1066.

These doves were free-flying but roosted in purpose-built dovecotes. However, some birds escaped and made nests for themselves elsewhere in the city – the original feral pigeons.

Pigeons have arguably the longest association with London of any bird. In 1385, the Bishop of London complained about people of a “malignant spirit” throwing stones, arrows and darts at the pigeons. But he was probably more concerned for the stained-glass of old St Paul’s Cathedral than for the birds.

Three hundred years later, writing about the 1666 Great Fire of London, Samuel Pepys described how “the poor pigeons… were loath to leave their houses, but hovered about the windows and balconies, till they burned their wings, and fell down.”

This Roman clay model of a pigeon was discovered on King William Street in the City of London and may have been used in religious customs.

Why are there so many pigeons in London?

London’s buildings make perfect nest sites, mimicking the windswept cliffs used by the birds’ ancestors.

And pigeons aren’t fussy eaters. They’ll happily eat grain, or McDonalds. On this varied diet, they live on average three to five years.

Pigeons pair for life and breed no matter the season. The chicks, called squabs, stay in the nest until almost fully grown – hence the urban myth that you never see their young.

“it was a natural aspiration in the inhabitants to connect themselves with any living creatures that could get out of that and fly into the air”

Charles Dickens

Pigeons have had their fans

In the late 20th century, writer Naomi Lewis went around London scattering birdseed to lure down pigeons tangled in string and nylon thread.

Once she’d caught them, she would nurse the birds back to health. Often she would take them to Conway Hall, Bloomsbury, where they could safely fly inside and gain strength before being released.

A prize card awarded to the winning Tumbler pigeon, a variety of fancy pigeon, at a show in Chiswick in 1889.

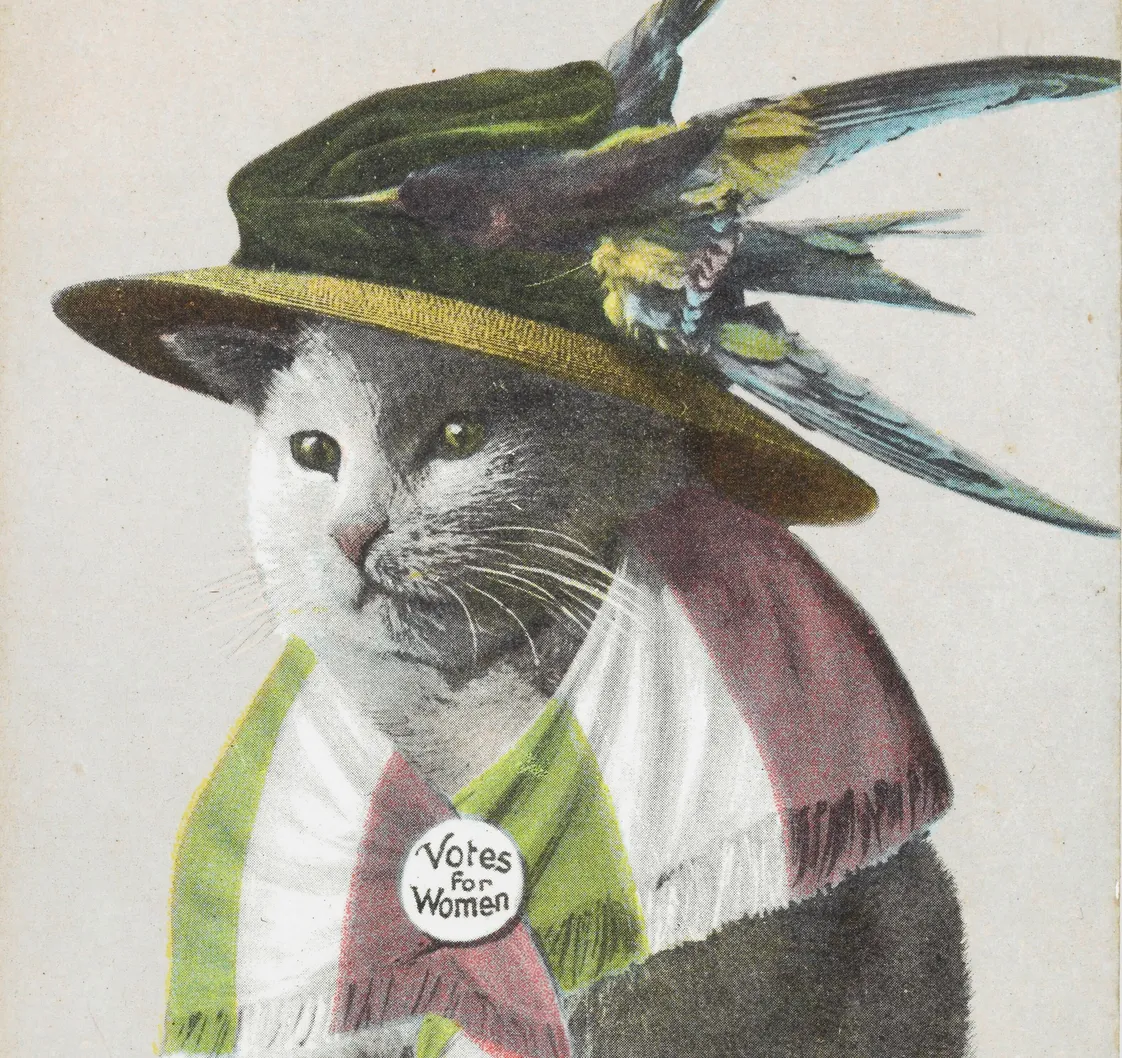

Pigeon fanciers

London also has a strong connection to pigeon fanciers. Fanciers are people who keep fancy pigeons. These birds are selectively bred for their pretty plumage, with varieties including fantails, pouters and tumblers.

During the 19th century, the month of May saw the markets at Leadenhall and Club Row crowded with fanciers buying the latest fancy pigeons.

The great 19th-century naturalist Charles Darwin was a member of the Southwark Columbarian Society, one of a number of fancier clubs in London.

Racing pigeons

Londoners have also used pigeons’ homing instinct to race them for sport.

The 19th-century writer Charles Dickens associated the East End’s many pigeon coops with a desire to escape the squalor of the London’s poorer districts, writing:

"you may connect a general idea that many pigeons are kept in Spitalfields, and you may remember to have thought, as you rattled along the dirty streets, observing the pigeon-hutches and pigeon-traps on the tops of the poor dwellings, that it was a natural aspiration in the inhabitants to connect themselves with any living creatures that could get out of that and fly into the air."

The homing instincts of pigeons continue to be used in London. In 2016, the campaign Pigeon Air Patrol attached backpacks to racing pigeons to record air pollution in London as they flew.

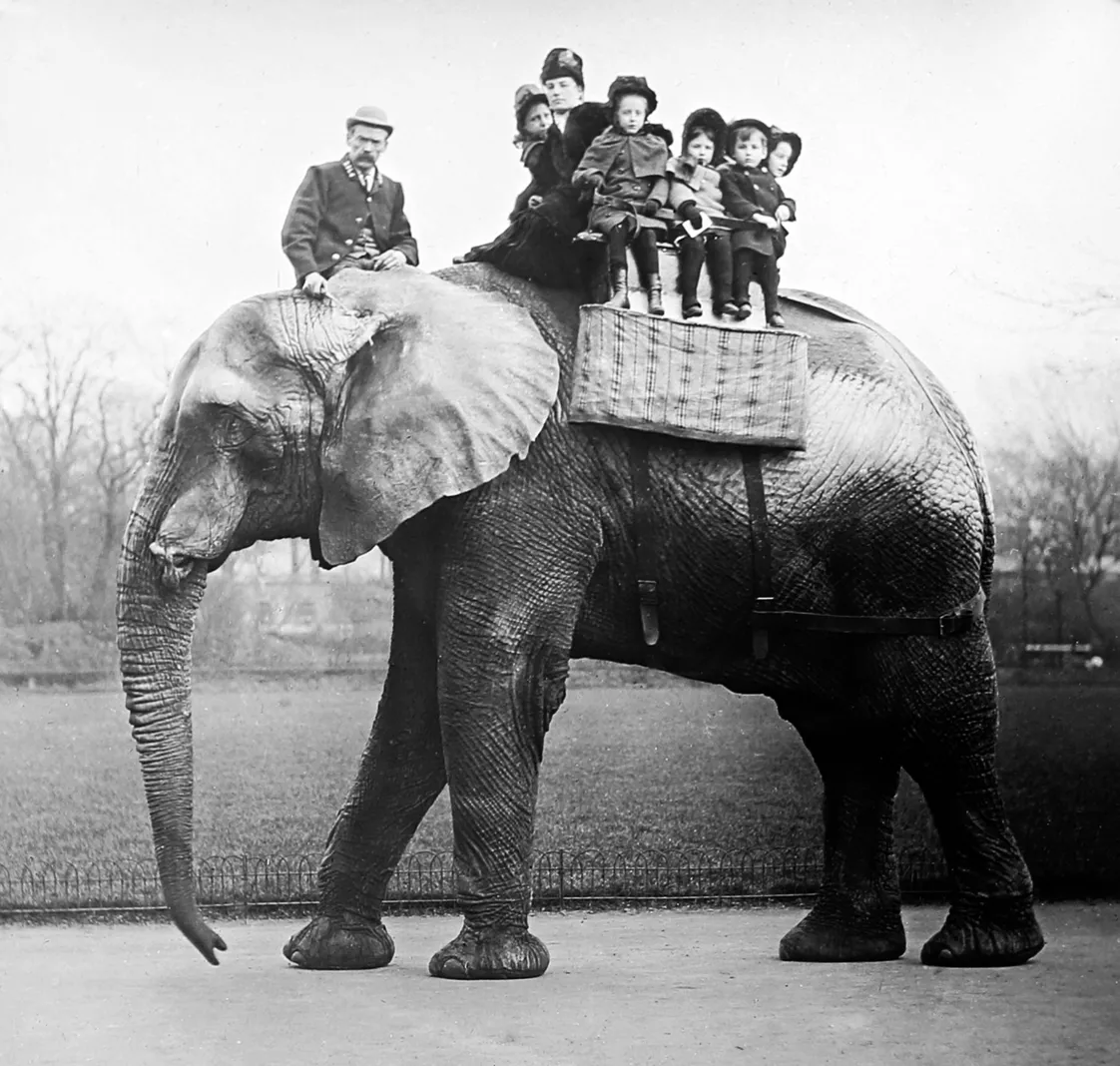

Pigeons in Trafalgar Square

Pigeons began flocking to Trafalgar Square even before the space was completed in 1844. Feed sellers soon established themselves, flogging bags of seed to visitors throughout the 19th and 20th centuries.

Trafalgar Square wasn’t alone – in the 19th century, Guildhall Yard was another popular place to feed the birds.

Pigeons, it seems, are capable of remembering both faces and places. If fed they will return to the same location and look for the same people. So, the more people fed them, the more pigeons returned to Trafalgar Square.

The record for the largest flock of pigeons on the square is, supposedly, 4,000 birds. When this was, or who did the counting, is not recorded.

A woman feeds pigeons in London in the 1950s, photographed by Henry Grant.

Trafalgar Square’s last birdfeed vendor

In 2000, the Greater London Authority stopped Bernie Rayner, Trafalgar Square’s resident birdfeed vendor, from selling grain to tourists. Rayner’s family had sold seeds in the square for half a century.

Are pigeons a problem?

Pigeons land on a person's head and arm, from around 1961.

Pigeons are often treated as pests – “rats with wings”.

They usually pose very little danger to us. But the massive number of birds, and the potential health risks associated with them, has long prompted authorities to control them.

Feral pigeons can carry a number of unpleasant infections, including psittacosis, histoplasmosis, cryptococcosis, E coli and salmonellosis.

Their poo also causes serious damage to stone. And pigeons aren’t sensitive to history – Nelson’s Column is just one London landmark requiring serious measures to keep the birds away.

Pigeons in our collection

As such an important part of London, pigeons appear frequently in our museum’s collection.

Culturally, pigeons and doves have a long association with love and marriage. An 18th-century Chelsea Porcelain tureen in our collection features doves who are “billing and cooing” – an old phrase for couples’ whispering and kissing.

The 18th-century heart-shaped pendant above continues the romantic theme. Made of gold and rock crystal, it holds two panels of silk embroidered with hair. One side shows a dove bearing a forget-me-not, the other a couple walking towards a house.

In the 20th century, a sculpture of two doves mating, by modernist sculptor Jacob Epstein, appeared in Holland Park, Kensington. And pigeons continue to inspire London’s artists and makers. The ring above, made by Tessa Metcalfe in 2018, is cast from the claw of a London pigeon.

Want to know more about the pigeon and our new brand?

Read our blog about the creatives and Londoners who worked in collaboration with us to come up with something truly unique.