The history of the Docklands Light Railway

The Docklands Light Railway – or DLR, as most Londoners know it – is a rail service built in the 1980s to regenerate London’s former docklands.

Docklands, east London

Since 1987

A ride through docklands history

The DLR now links east and south-east London, crossing under the Thames and taking you from Stratford to Lewisham, or from Bank to Woolwich Arsenal.

If you take a DLR train today, what do you see? Maybe Canary Wharf’s glass towers, Stratford’s Olympic Park or London City Airport.

But the docklands at the heart of this rail line was once London’s port, alive with the activity of an international trade centre.

The area lost this industry in the 1970s, but change began to arrive on the DLR.

Docklands before the DLR

London’s port was the trading hub of the British empire. In the 18th and 19th centuries, it played a part in the British trade in enslaved Africans, with the West India Docks built to receive goods produced by enslaved people in the Caribbean. Other docks received goods from other parts of the world – the East India Docks, for example, brought in goods from Asia.

The West India Docks that this steamer passed through in 1934 have now been replaced by a financial district.

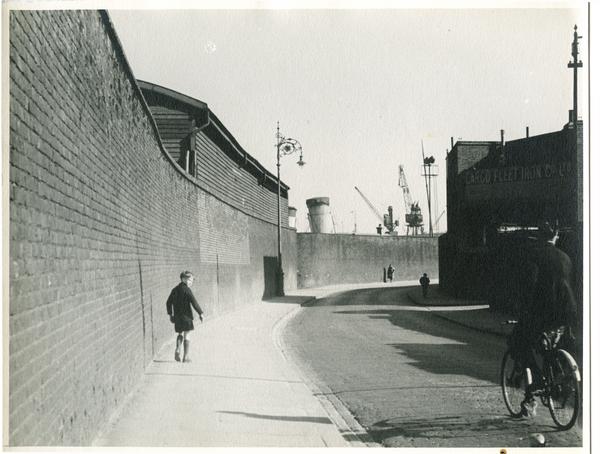

As shipping changed in the 20th century, east London’s docks became less ideal. Bigger ships and containers required a new style of port.

In the 1970s, the Port of London’s freight-handling facilities moved to the deep-water container port at Tilbury, Essex. The centuries-old London docks were abandoned, with the loss of thousands of jobs. The area quickly became derelict.

Redevelopment of the docklands

In 1981, the London Dockland Development Corporation (LDDC) was formed by Margaret Thatcher’s government to regenerate the area. Working with private developer Trafalgar House and the Greater London Council, one of the LDDC’s ideas was to build a light railway.

A royal passenger riding the DLR on its opening in 1987.

Queen Elizabeth II opened the DLR on 30 July 1987. It had 15 stations, and the line finished at Tower Gateway, Stratford and Island Gardens. The first passenger service ran on 31 August, and an estimated 40,000 people travelled that day.

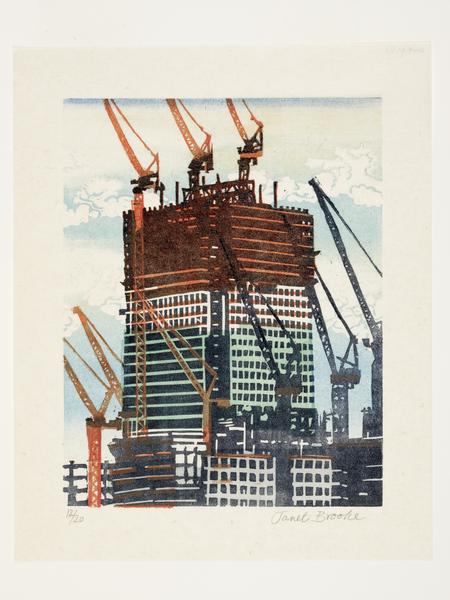

The DLR was part of a wider transformation of the docklands in the 1980s, led by the LDDC. Rewards were offered to developers who built offices in a newly created enterprise zone. The Isle of Dogs morphed into the Canary Wharf financial district, home to bankers, lawyers and glass towers like One Canada Square.

This period of change triggered protest. Canary Wharf faced opposition from the local community, and there was resistance to the lack of affordable housing being constructed. But the development continued regardless.

One Canada Square became a symbol of the docklands' redevelopment and the new financial district.

Improving and extending the DLR

Extensions to the DLR came thick and fast: to Bank in 1991, to Beckton in 1994, to Lewisham in 1999, from Canning Town to City Airport and King George V station in 2005, and to Stratford International in time for the 2012 Olympic Games. In 2023, an extension to Thamesmead was proposed.

In the 1990s, the Jubilee Line was also extended to link up with the DLR at Canary Wharf, where a new, larger station designed by Sir Norman Foster was built in a drained part of the West India Docks.

“DLR trains have always been driverless”

DLR has been looked after by Transport for London since it was founded in 2000. In 2024, the line received new trains, with walk-through carriages, charging points, air conditioning and a turquoise colour scheme.

But its most futuristic aspect has been there since the start. DLR trains have always been driverless, although staff on board can drive if needed.

That driverless design means passengers can take seats at the very front, giving you a perfect view of the docklands as you pass through.