Heaven: London’s gay superclub

A home of LGBTQ+ club nights, live music, drag and early rave scenes, this iconic central London venue has constantly reinvented itself.

City of Westminster

1979

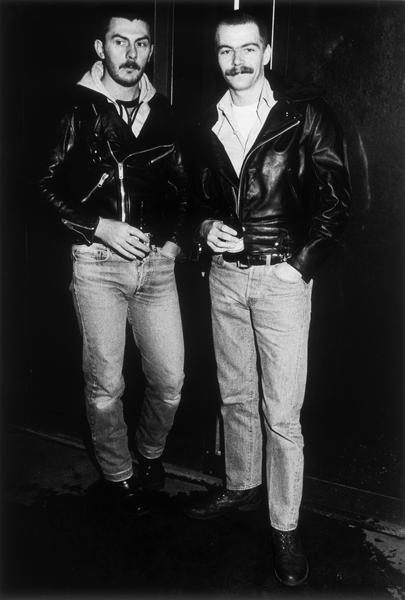

A Gatecrasher party at Heaven, Charing Cross.

The club that shook up London nightlife

Under the arches of Charing Cross Station, one of the capital’s longest-running LGBTQ+ venues continues to make noise seven days a week.

In 1979, nightclub entrepreneur Jeremy Norman transformed a run-down roller disco into a vast, multi-room club fit to rival New York’s renowned Paradise Garage. It became a foundational venue that brought gay nightlife into the mainstream and nurtured early house, techno, jungle and drum and bass scenes.

Heaven’s musical choice and clientele have evolved over the years – it now hosts student nights and pop gigs as well as long-running queer parties.

DJ John Digweed's house night Bedrock booked names like Carl Cox and Grooverider.

A new kind of club

Around the time of Heaven’s grand opening, London’s LGBTQ+ nightlife was largely confined to members clubs and pubs. In 1976, a popular gay party called Bang! (which became G-A-Y in the 1990s, and still runs as a bar in Soho) brought disco and over 1,000 dancers to the basement of the Astoria on Monday nights. But a dedicated gay club of that size didn’t yet exist.

“a multi-room playground with high-tech lighting and a roaring sound system”

Heaven opened in 1979 as a multi-room playground with high-tech lighting and a roaring sound system. The club’s first resident DJ, Ian Levine, pioneered the emerging sounds of Hi-NRG, a faster style of disco or electronic music that became hugely popular in gay clubs in the 80s. Think bright synthesisers, shouty vocals and, as the name suggests, high-energy basslines.

The club had quite a strict ‘gay men-only’ door policy, especially at the weekends. Norman wanted to ensure it remained a safe place where gay men could meet each other. Barely a decade had passed since the 1967 Sexual Offences Act which decriminalised “homosexual acts in private”, and LGBTQ+ people still faced widespread prejudice in British society.

Nurturing UK rave sounds

In the 1980s and 90s, Heaven’s sound – and its clientele – grew and diversified as the club nurtured emerging UK rave subcultures.

New Romantics dancing the night away at Heaven in 1980.

Wednesday club night Pyramid was one of the first to play house music hailing from Chicago in the mid-80s. In the late 80s, Monday night party Spectrum pushed forward house music’s pounding and squelching subgenre, acid house. And around the same time, Thursday’s Rage had the futuristic, breakbeat-heavy sounds of hardcore – the foundations of jungle and drum and bass – lashing through the sound system.

Some of these nights began attracting straight crowds into Heaven’s hallowed halls. But it remained primarily a gay venue. The drag-focused Fruit Machine, for example, hosted by Miss Kimberley, took over on Wednesday nights in the 90s.

Still an iconic London LGBTQ+ venue

Heaven continues to offer a programme of live music. New Order, Nick Cave and Throbbing Gristle played there in the early 80s. And pop stars Sade, Madonna and Cher have all also graced the stage.

The club’s music programme has leant more commercial in recent years. Popcorn, its trademark pop and R&B-focused Monday party, has been running since 1998. In 2013, Heaven was acquired by G-A-Y founder Jeremy Joseph, and it now hosts the renowned G-A-Y club night that once took place at the Astoria.

In 2020, the club was awarded the status of Asset of Community Value. This acknowledges its importance to London’s LGBTQ+ community and protects it from being sold to property developers for five years. The following year, during the Covid-19 pandemic, it was transformed into a pop-up vaccination clinic.

But its future is at risk

In early 2024, Heaven was served a rent increase of an additional £320,000 by its landlord – putting the venue at risk of closure. Other LGBTQ+ venues across London have faced similar threats in recent years, including the Black Cap in Camden, whose owners attempted to turn the building into luxury flats.

“We are not the only venue that is at risk because of landlords,” Joseph wrote on an Instagram post. “It’s time to fight back and protect hospitality, too many venues have closed.”