Harrods: A location for luxury

Think of Harrods, and you probably think of luxury and abundance. But this world famous department store, one of the largest in Europe, came from quite humble beginnings.

Kensington & Chelsea

1849

A family-run grocer becomes a London landmark

Stroll down Brompton Road from Knightsbridge tube station and you’ll soon arrive at one of London’s most lavish department stores.

Harrods, with its distinctive green awnings and ornate gold facade, is an emporium that occupies an entire block of wealthy west London. The store's eight floors are home to more than 330 departments, many of which sell goods that come with a hefty price tag.

It may be a destination for designer goods today. But back in the mid-19th century, Harrods actually began selling groceries and tea in the capital’s East End. As it expanded, it built up a reputation as a one-stop shop for everything a customer might need.

The Harrods food hall.

Harrods has a long history in groceries and tea

Harrods takes its name from its founder, Essex-born Charles Henry Harrod. He sold textiles in Borough in the 1820s before becoming a wholesale grocer, first in Clerkenwell, then Stepney in the early 1830s. In 1849, maybe hoping to benefit from the 1851 Great Exhibition in nearby Hyde Park, Harrod moved his trade from the East End to a small shop in the fashionable district of Knightsbridge.

The grocers passed hands to his son, Charles Digby, in the early 1860s. Harrods grew over the next 20 years. By 1880, it employed nearly 100 people and sold medicines, perfumes and stationary as well as fruit and veg.

Harrods expanded

Disaster struck in December 1883 when the shop building was destroyed by fire. Impressively, Harrods still managed to fulfil their Christmas orders. An even bigger store reopened in 1884. Turnover more than doubled.

Charles Digby retired in 1889 and sold the company. The new firm kept the Harrod family name, given its reputation for quality business and customer service.

Present-day Harrods, big enough to get lost in.

By the early 1890s, the store had either expanded into or agreed to acquire most of the current site we see today. Harrods even boasted London’s first escalator, installed in 1898. On the day it opened, staff stood at the top offering out brandy to customers a little freaked out by the experience.

“The most elegant and commodious emporium in the world”

The department store that had it all

At the turn of the 20th century, it became Europe’s biggest department store. It was, according to one 1915 Harrods postcard, “The most elegant and commodious emporium in the world.”

Harrods didn’t just boast a vast range of shops. The store had waiting rooms, fitting rooms, smoking rooms, a post office, a circulating library, a music room, a tourist office, booths to book theatre tickets or train tickets.

It also had a pet shop between 1917 and 2014. You could even buy an alligator, elephant or lion there – at least until the 1970s, when the Endangered Species Act stopped the sale of ‘exotic’ animals.

Harrods' Way In boutique

Into the 1950s and 1960s, independent boutiques, like Mary Quant’s Bazaar or Barbara Hulanicki’s Biba, started popping up across London. They offered young people a new way of buying clothes.

Department stores responded by opening their own in-house boutiques, like Selfridges’ Miss Selfridge, which opened in 1966. Harrods launched their Way In boutique in 1967. It stocked youth-focused fashion, records and books and had a restaurant and juice bar.

Women and men’s clothes were also displayed together in the same area, which was quite a radical concept for department stores at that time.

Modelling Way In clothes in 1967.

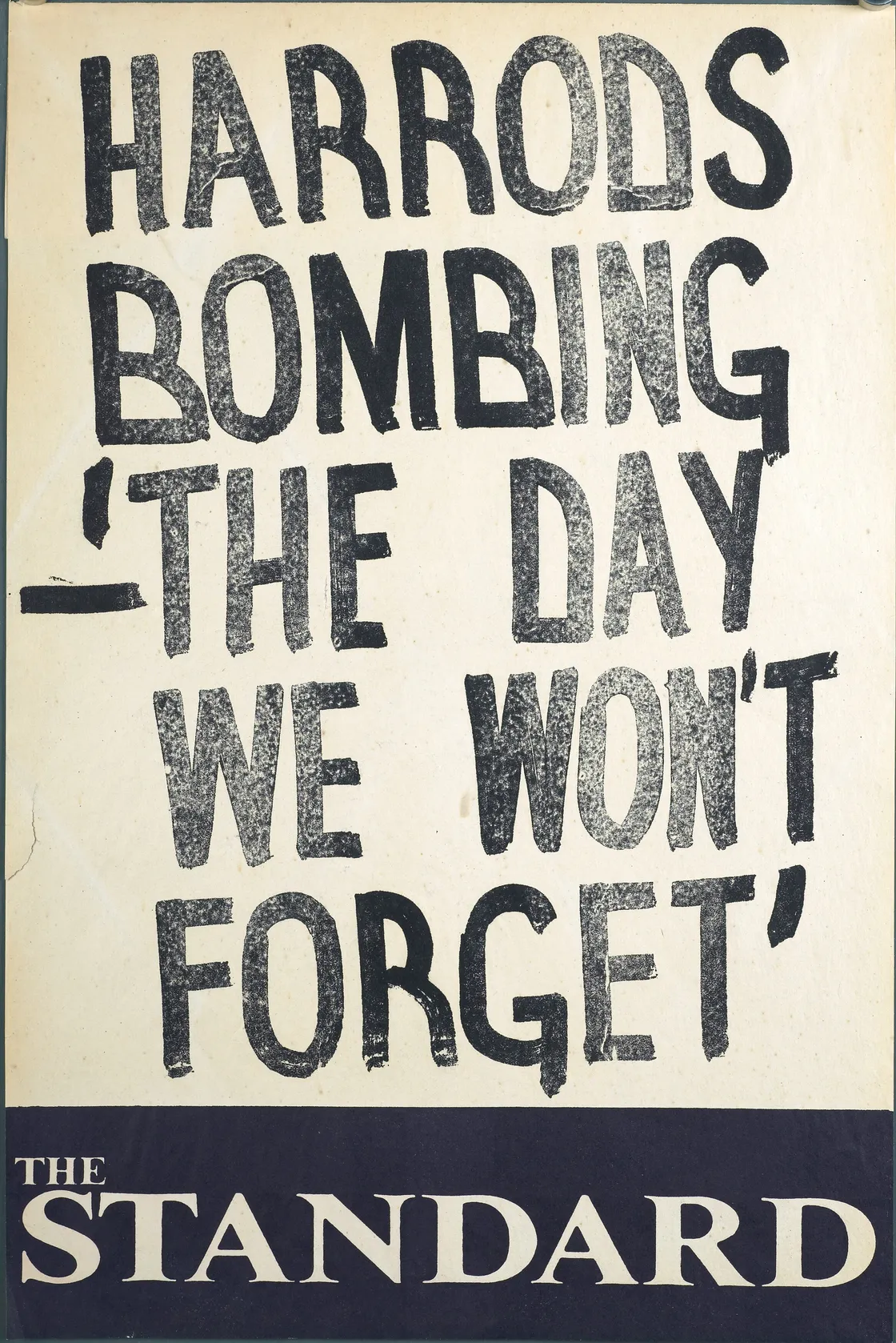

The 1983 Christmas bombing

At 1.21pm on Saturday 17 December 1983, a car bomb exploded outside Harrods. It killed three police officers and three civilians and injured 91 people. The blast blew out windows in the building, sending glass flying through the streets and into the shop. The Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher described the attack as a ''wicked crime against humanity and a crime against Christmas, too.''

The Provisional IRA (Irish Republican Army), an Irish paramilitary organisation, admitted responsibility, but no one was ever charged. The IRA had carried out bombing campaigns in London from 1973 targeting high profile and often crowded buildings.

Evening Standard billboard from 1983.

London Museum has a number of objects relating to the 1983 attack. They starkly contrast the goods bought and sold at the store over its long history.