The Great Stink of 1858

In the hot summer of 1858, London’s booming population suffered as the River Thames started to pong – a smell so bad it caused a sewer revolution.

River Thames

1858

A very smelly summer in the city

Modern London can be a grimy place. It often smells. But 1858’s Great Stink was on another level.

London had outgrown the city’s waste-disposal customs, causing poo and worse to clog the Thames, smaller rivers and even the city’s streets.

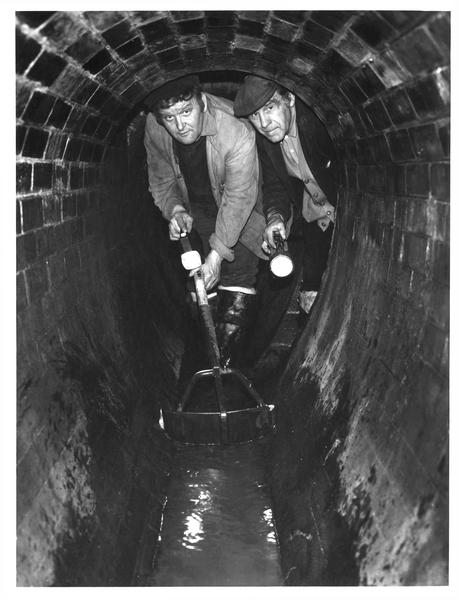

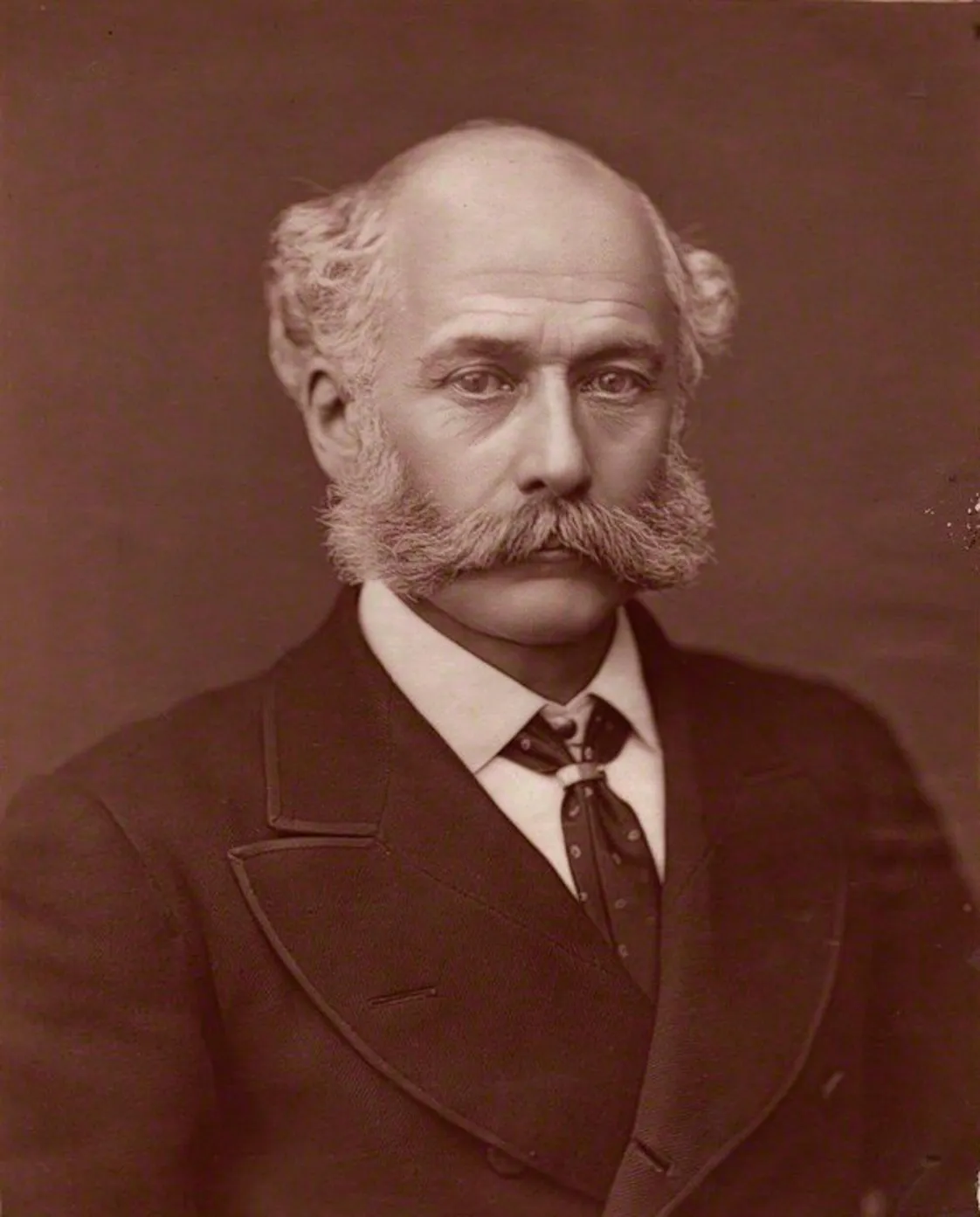

One hot, dry summer sent the smells into overdrive. The government responded, and engineer Joseph Bazalgette was asked to provide a solution. The brick-lined tunnels he built still form the basis of London’s sewers today.

Population explosion overwhelms the city

London’s population doubled between 1800 and the 1850s. At the time of the Great Stink, with Queen Victoria on the throne, London had a population of over 2.5 million, making it the largest city in the world.

More people equals more waste, and London wasn’t prepared.

“Londoners still used the dirty Thames for drinking and washing”

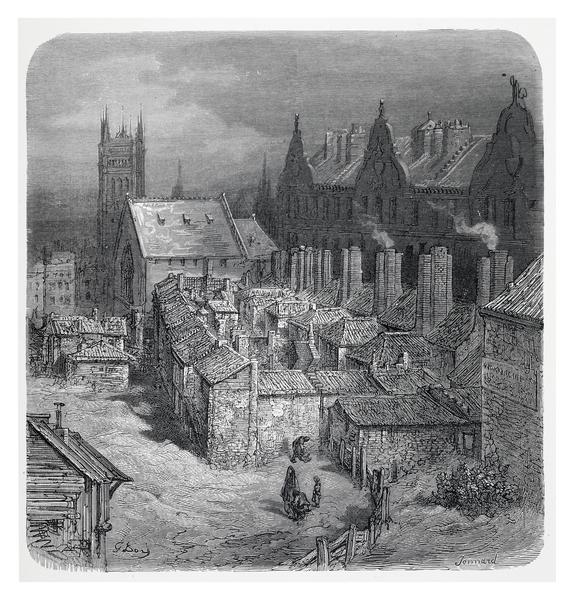

In this neighbourhood of Westminster, the artist wondered "whether such filth and squalor can ever be exceeded".

Where did the smell come from?

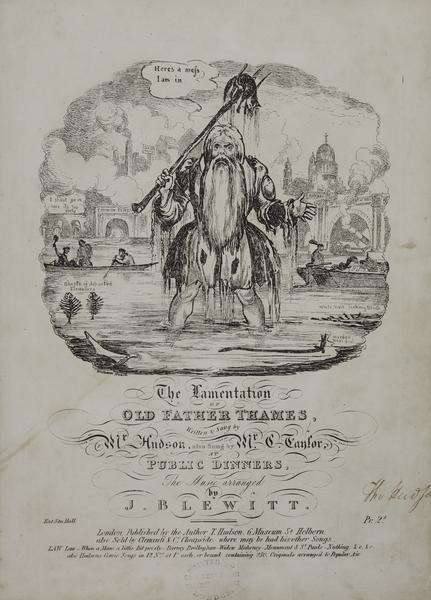

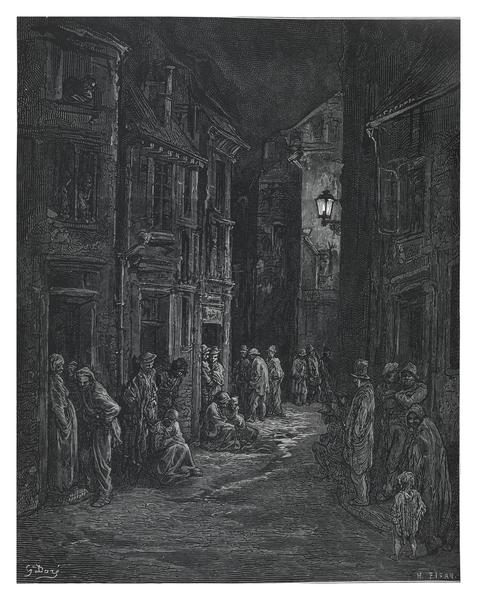

In the 1850s, waste of all types ended up in the River Thames. There was human poo and wee, dead animals, thrown-away food, industrial waste from riverside factories, and the bodies of anyone who drowned.

In the streets, manure piled up from the horse-drawn carriages.

In 1858, temperatures hit 30 degrees and stayed high for weeks. The river sank lower than normal, leaving sewage on the river banks. The filth baked in the heat of the unusually hot summer. The smell was worse than ever before.

What did it smell like? Nauseating, literally – people are reported to have vomited if they went too close to the Thames.

A city full of disease

Worse than the smell, the rotting waste also spread disease.

At the time, people didn’t think diseases were spread by water. Londoners still used the dirty Thames for drinking and washing.

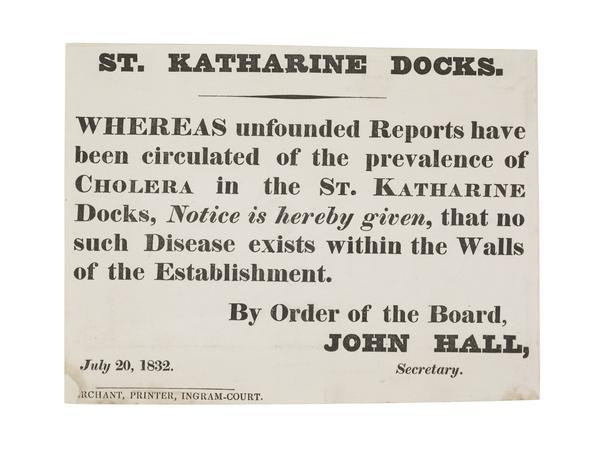

During the summer of the Great Stink, cholera and typhoid spread quickly. People blamed the smell itself – what they called the “miasma”.

How did people react to the Great Stink?

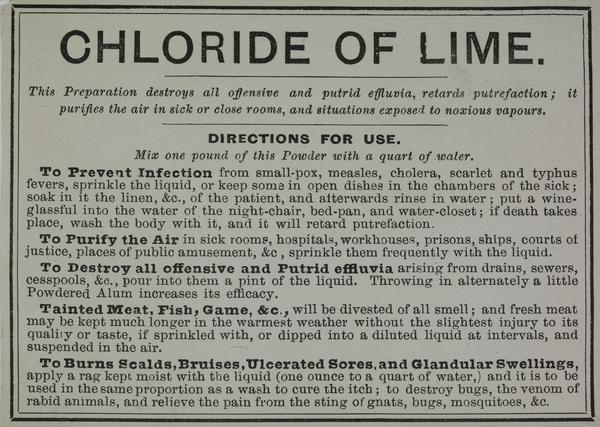

Anyone who could afford to left the city. Otherwise Londoners stayed indoors. Curtains and blinds were soaked in chloride of lime to block the smell.

Parliament was sitting that summer, and MPs felt the full force of the stink. Outside their windows, waste baked on the exposed riverbeds, and the thickened Thames crawled by.

The government rushed through a bill, proposed by Benjamin Disraeli, to fund a new sewer. The bill became law in just 18 days.

Wasn’t there a sewage system already?

For centuries, London depended on inconsistent local waste disposal, including night-soil collectors who emptied cesspits.

Smaller rivers like the Fleet and the Tyburn, which ran into the Thames, were a common place to empty the contents of chamber pots. Charles Dickens describes the situation in his 1850s novel Little Dorrit: “Through the heart of the town a deadly sewer ebbed and flowed, in the place of a fine fresh river.”

The increasingly popular flushing toilet made things worse, letting wealthy families send their poo directly to the river.

The Metropolitan Board of Works had wanted to improve London's sewers for years, but didn't have the money.

The extensive construction which followed the Great Stink included building embankments along the Thames.

Bazalgette’s sewer solution

With new funding, the Metropolitan Board of Works hired Joseph Bazalgette to address the problem.

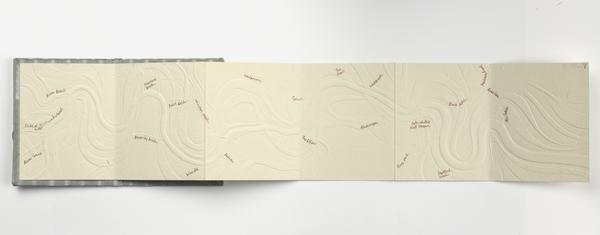

His solution was a sprawling network of underground tunnels. The tunnels connected local drains, sending waste downstream with the help of pumping stations at Deptford and Abbey Mills. The River Fleet was diverted underground, becoming part of the sewers.

Bazalgette’s project was eventually completed in 1875. His sewers have been used in the capital for centuries since, but London’s 21st century population eventually merited an upgrade. Construction of a new “super sewer”, the Thames Tideway Tunnel, began in 2016.