The Great Fire of London

The Great Fire of London scorched four fifths of the city in 1666, leaving around 100,000 people homeless. The scale of the destruction means it’s been remembered ever since.

City of London

2–6 September 1666

London in flames

Picture standing on the south side of London Bridge looking north at the City. Everywhere you look there is smoke and fire. Flames climb church towers. Desperate Londoners clog the river, packing whatever they can into boats.

There’s a reason the Great Fire is still so widely known. The scale of destruction was terrible. It shocked and scarred Londoners to see their city’s “glory laid to dust” – something many could never have imagined.

Starting in a bakery on Pudding Lane in the east of the City, the fire spread from house to house, through churches and grand halls, only stopping four days later. Buildings were pulled down and blown up to stop it. When the fires died, blame spread.

Although grand plans were made to build a new London, the city was largely remade on its old foundations.

How did the Great Fire of London start?

The fire began at around 1am in a bakery on Pudding Lane owned by Thomas Farriner.

Pudding Lane is in the south-eastern part of the City of London, a short walk from the River Thames. Today, the famous monument to the Great Fire is close by.

We can’t know for sure how the fire started. It’s possible that a spark from one of Farriner’s ovens set light to a pile of wood.

We think the first person to notice the fire might have been Thomas Dagger, a 24-year-old apprentice to Farriner. He woke up to “the choke of the smoke” and rescued the rest of the people in the house, helping them escape through an upstairs window.

How long did the Great Fire last?

The fire lasted for four days. Samuel Pepys described it as “an infinite great fire”.

It spread quickly from the bakery. Houses in Pudding Lane stored tar, rope, oil and brandy, which set fire easily. There had been a dry summer. Wooden houses were crammed close together. Strong winds blew the fire west.

“there was nothing heard, or seen, but crying out and lamentation”

John Evelyn

What did the Great Fire destroy?

The flames ran riot through the city, going east to the Tower of London and west as far as the Temple. The scale of destruction was greater than the Blitz in the 1940s.

The fire claimed 13,200 houses and 87 churches. It tore through Cheapside, London’s main street. It destroyed the Guildhall – the home of London’s government. And it wrecked the old St Paul’s Cathedral.

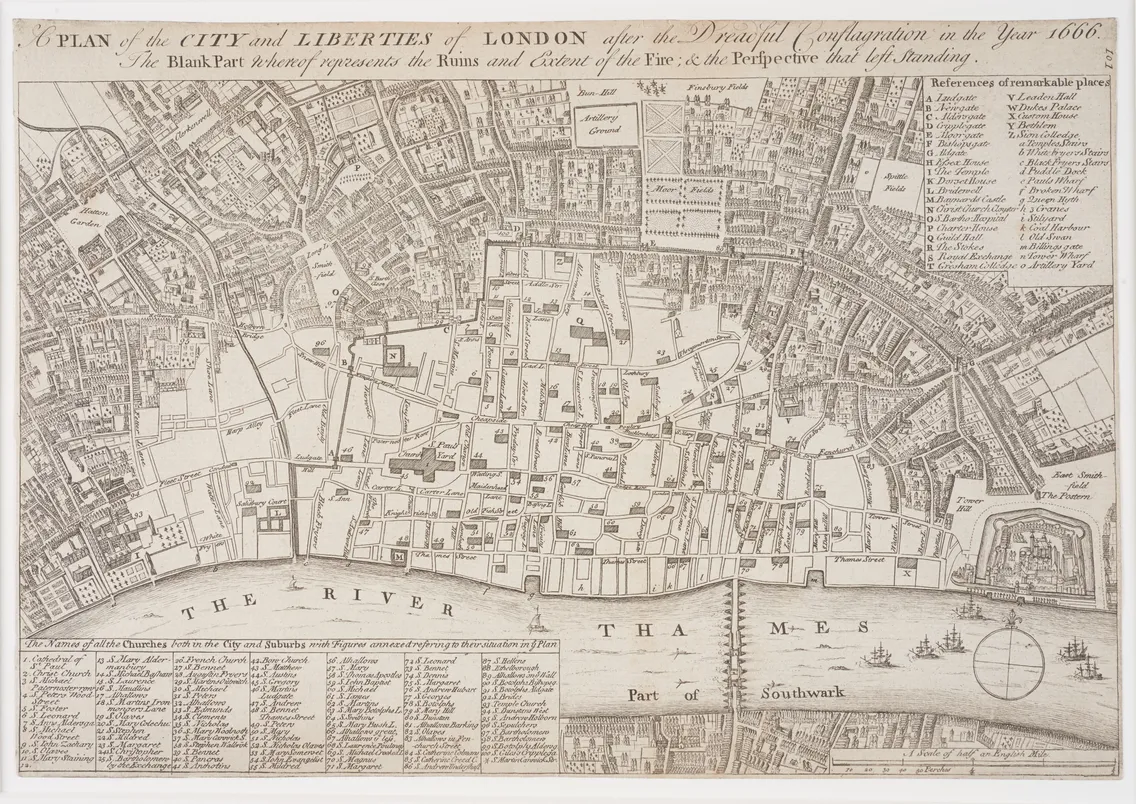

In this plan of the city from our collection, the area destroyed by fire is shown in white. When archaeologists dig in London, they often find a layer of scorched debris from the fire – a lot of it has ended up in our collection.

How many people died in the Great Fire?

Fewer than 10 people are recorded to have died during the fire. It’s possible more died, but we think there was enough time for most to escape.

Still, the impact on Londoners was devastating. Around 100,000 people were left homeless, their possessions and business in ashes.

How did Londoners react?

Most rushed to escape, taking their valued possessions with them. One Londoner described the “exceeding great confusion and throng of people and quantity of gross and bulky goods turned out into the streets and lanes”. Some fled to the river. Others headed to the fields outside the city walls.

John Evelyn describes how people were too overwhelmed to fight the fire: “they hardly stirred to quench it so that there was nothing heard, or seen, but crying out and lamentation.”

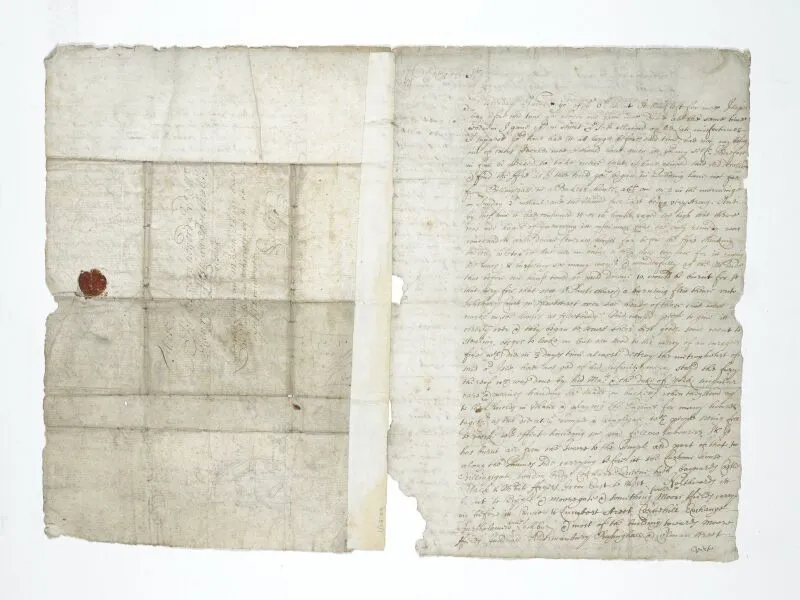

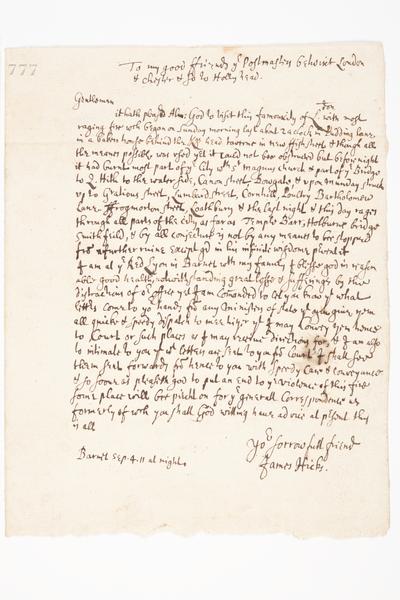

In the days after the fire, Londoners wrote revealing letters to relatives and friends describing the disaster. In one from our collection, Henry Griffith mentions looting during the fire: “some went to stealing, others to look on”.

How was the Great Fire stopped?

There was no fire brigade at the time – instead, local people were meant to club together to help. Each parish kept water buckets and hooks to pull down buildings to slow the fire. Some had simple fire extinguishers which worked like a large syringe.

The Lord Mayor, Thomas Bludworth, checked the fire soon after it started. Thinking it wasn’t serious, he went back to bed. As the fire got worse, firefighters did pull down some houses to slow the fire. But the fires spread too quickly.

Soldiers were called in to help. On the third day of the fire, gunpowder was used to destroy buildings more quickly. The wind got weaker too, slowing the fire’s spread. By the fourth day, the fire was under control.

Who was king at the time of the Great Fire?

Charles II was on the throne in 1666. The king commanded the Lord Mayor to “spare no houses, but to pull [them] down before the fire every way.” During the fire Charles rode through the city, giving out money to persuade people to fight the flames.

Afterwards, he ordered bread to feed the homeless and asked people in the surrounding towns to house them.

He ordered a day of national fundraising for London. A receipt from our collection shows the offering from a village in Sussex. Overall, £12,000 was raised – not enough to make a big difference.

“Some thought God was punishing Londoners for eating too much”

Who was blamed for the Great Fire?

Thomas Farriner escaped blame. But suspicion was cast in several directions.

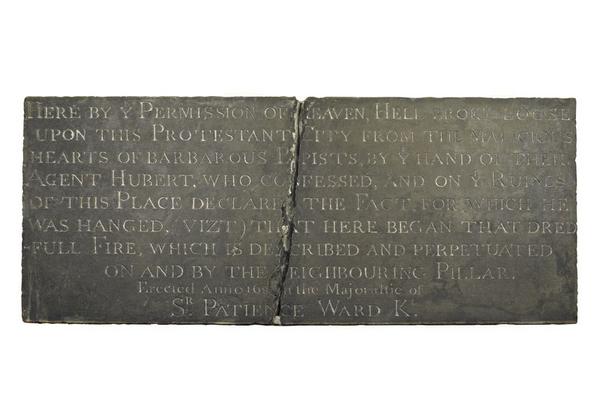

People suspected France and the Netherlands, because England was at war with them. Catholics were suspected of wanting to destroy London, a Protestant city. Then Robert Hubert, a Frenchman who may have suffered mental health problems, confessed to starting the fire. He was executed in 1666, but it was later realised that he wasn’t in London during the fire.

Some thought God was punishing Londoners for eating too much. That was based on the incorrect belief that the fire had stopped at Pye Corner in Smithfield.

A parliamentary inquiry concluded the fire was an accident.

“most of the City of London’s streets follow a similar route to 500 years ago”

Many plans proposed to rebuild London in a more ordered way, but none became reality.

How was London rebuilt after the Great Fire?

The fire was a chance to change London’s twisting, narrow, dirty streets and mish-mash of buildings. Different plans were proposed to make the city more like Paris or Rome.

In our collection, you can see plans submitted by John Evelyn and Christopher Wren to introduce wide streets organised in a grid structure, with large public squares.

None became reality. The complexity of coordinating with all the property-owners was immense. People couldn’t afford to wait to get back to their lives.

Rebuilding began on old foundations. Many buildings’ outer walls followed the same outline they had previously. Most buildings had the same function as before the fire. Even today, most of the City of London’s streets follow a similar route to 500 years ago.

By 1676, almost all of the damaged area had been rebuilt. Some streets were slightly wider. Many wooden buildings were rebuilt in brick or stone.

St Paul’s Cathedral, designed by Christopher Wren, rose again, now with its iconic dome.