How the Great Fire caused a London housing crisis

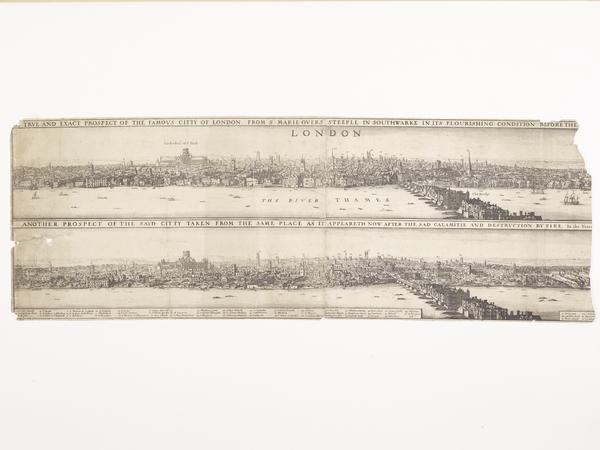

When the Great Fire of London destroyed four fifths of the city in 1666, it created a housing crisis not unlike today’s situation. Here’s how Londoners rebuilt – or didn't – after the disaster.

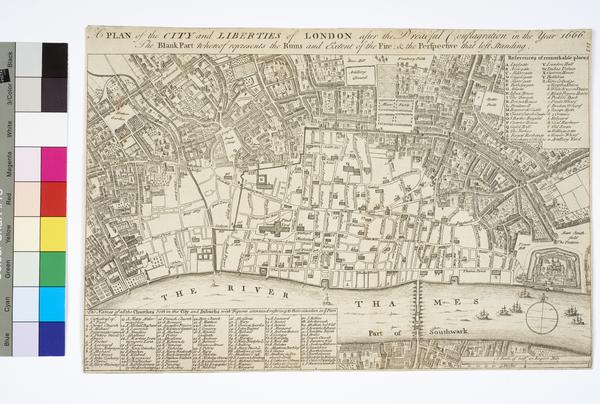

City of London

1666

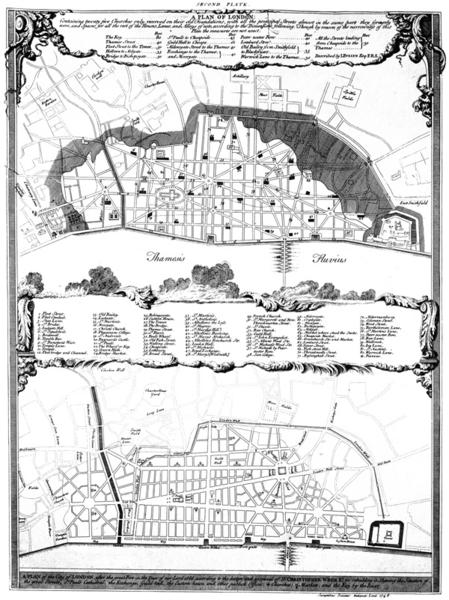

The clear white area in the centre of this map shows the area devastated by the fire.

Tens of thousands homeless

Londoners today face a housing crisis caused by ever-increasing prices and a lack of affordable housing. People are moving further away from central London, or the areas where they grew up. Many are abandoning the city altogether.

The results of this crisis would have been familiar to the Londoners of 1666, though the cause was very different.

After the fire, landlords hiked rents. People crammed into smaller homes, in areas they’d rather not have moved to.

The 1666 crisis eventually eased as the city was rebuilt. Which leaves us asking – what will the solution be to our own crisis?

Destruction and homelessness

Four fifths of London was destroyed in the fire, which began on 2 September 1666. Within five days, around 13,200 houses were in ruins and around 100,000 Londoners were homeless.

Reeling from their losses, people had to decide what to do next. Thousands camped in the fields outside the city in tents and shacks.

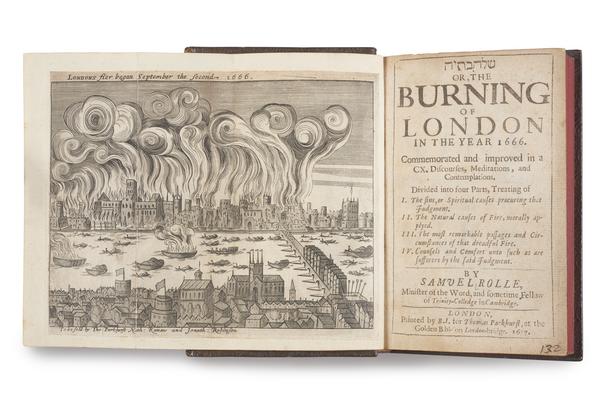

“Is London a village that I see, the houses in it stand so scatteringly?”

Samuel Rolle, 1668

Temporary solutions

The City of London authorities rented out fields so that people could build temporary homes. Shanty towns grew up in places like Moorfields.

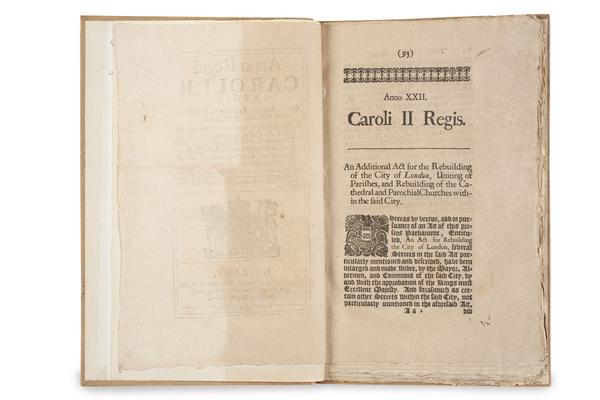

This was only a short-term solution. The Additional Rebuilding Act of 1670 stated that “sheds, shops and other buildings” which had popped up in “Smithfield, Moor-fields; and other void places” had to be removed by 29 September 1674.

In other words, up to eight years after the fire, some Londoners were still living in these shanty towns.

Rising rents

Those who could afford to could move to one of the unburnt areas of London. But many landlords who had not lost their properties in the fire raised their rents immediately.

On 7 September 1666, the famous diarist Samuel Pepys noted: “strange to hear what is bid for houses all up and down here… £150 for what [someone] used to let for £40 per [year]”.

Thomas Bromfield wrote a letter to his wife on 17 September, saying that “houses are ten times dearer than ever they were.”

17th-century trade tokens like these give us valuable information about the locations of businesses at the time of the fire.

Trade tokens

Looking at our collection of 17th century trade tokens turns up some evidence for Londoner’s post-fire moves.

These tokens were unofficial coins handed out by small businesses as change, and were stamped with the business owner’s name and location.

Ralph Butcher’s story is one example. A token from 1664 shows he owned a business in Tower Street. But another from 1666 is issued from “without Bishopsgate”, an area which escaped damage. It’s likely that he moved here after his previous business was destroyed in the fire.

Moving within London

In his 1667 book Samuel Rolle commented on the migration of rich citizens from the burnt-out city to poorer suburban areas:

“How much more considerable are the suburbs now, than that lately were? Some places of despicable termination, and as mean account, but a few months since, such as Houndsditch, and Shoreditch, do now contain not a few citizens of very good fashion… Time was that rich citizens would almost have held their noses, if they had passed by those places where now it may be they are constrained to dwell”.

If you found a property in the surviving areas of London, you may not have been able to live in the comfort you were used to.

In a 1668 book, Rolle says that many people complained of being “pent up” in small, “unsweet and unpleasant” dwellings where it was difficult to work or house their families.

That might sound familiar to some Londoners today, where the housing squeeze has seen attics and basements offered for rent.

Moving out of London

Others left London entirely. A declaration from King Charles II in 1666 encouraged towns to take in homeless Londoners.

Rolle says Londoners were “dispersed and scattered into corners, some crowded into the suburbs, others gone into the country, disabled in all likelihood, from ever returning again, to settle as before.”

The same is happening today as high house prices drive an exodus of London residents into distant suburbs and satellite cities such as Brighton and Reading.

Rebuilding London

Many saw the gigantic task of rebuilding the city as an opportunity for change. The architect Christopher Wren and the writer John Evelyn, among others, submitted designs to sweep away the cramped streets of old London, replacing the muddled medieval city with orderly, open avenues and plazas. Copies of these plans are held in our collection.

But much of the land in the City of London was privately owned, with a complicated mix of landlords, tenants and sub-tenants.

Cutting across this complex tangle of rights with an ambitious new street plan was not a priority in 1666. Londoners needed new homes as quickly as possible.

In the end, the winding streets of the medieval city were restored in the rebuilt London. This dense network of roads has guided the future growth of the city, even into the 21st century. It remains difficult to build American-style skyscrapers amid the narrow lanes and small blocks of the City of London.

St Paul's Cathedral, rebuilt to the designs of Christopher Wren, still influences London's planning regulations. New buildings must not block certain "protected views" of the cathedral from locations as distant as Richmond or Parliament Hill.