Frost fairs: Festivities on a frozen River Thames

In London’s coldest winters, particularly between the 1600s and 1800s, the Thames could freeze over. Londoners would take to the ice and host frost fairs, which were part market, part fun fair and part carnival.

River Thames

1600s–1800s

A long-lost winter wonderland on ice

From the early 1600s to the early 1800s, the surface of the River Thames froze over 24 times. Sometimes it stayed frozen for several weeks.

So what did Londoners do when trade and travel on this vital river ground to a standstill? They simply brought bustling street life onto the ice – and added some extra attractions.

Frost fairs were first set up so that people could travel and trade on the river. But they eventually evolved into full-blown festivals featuring all kinds of entertainment and activities, such as hunting, skating and bowling.

Why were London’s winters so cold?

From the early 1300s to the mid-1800s, countries north of the equator, including Britain, experienced cooler than normal weather. This has been called the “Little Ice Age”. The global temperature is thought to have dropped by 0.5C during this period.

Frost fairs involved hunting, skating and bowling.

Why did the River Thames freeze over?

Winters were much harsher during the Little Ice Age, and the capital’s lakes and rivers could freeze over in the coldest temperatures. But the Thames also looked different back then, being wider and shallower than it is today. The water flowed more slowly, so it froze even more easily.

The design of the old stone London Bridge, which stood from 1209 to 1832, also broke up the river flow. It featured 19 closely spaced arches supported by small piers. These could get blocked with ice and debris, effectively damming the Thames and slowing the river further.

Why did Londoners hold frost fairs?

The Thames was an essential part of daily life for Londoners. When it froze, people could no longer trade or travel by boat. So they’d take to the ice to trade and to get from A to B. Some enterprising bargemen and sailmen, temporarily unable to work, earned money by guiding sightseers on the ice.

“Carnival on the water”

John Evelyn

A frozen Thames also presented another opportunity: fun. In the first event officially recorded as a “frost fair” during the winter of 1607–1608, there were football pitches and bowling matches among the camps of traders.

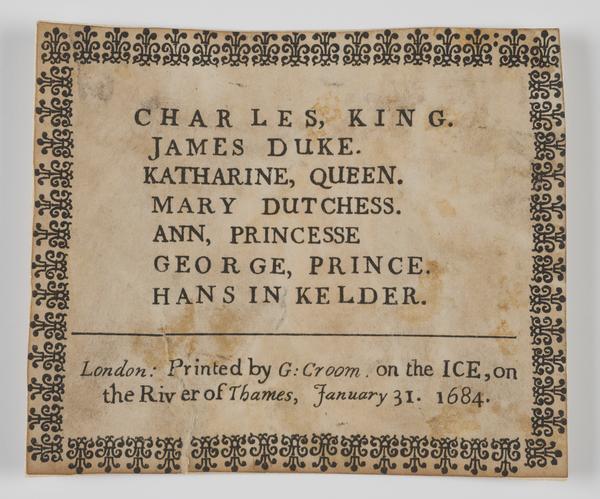

Eventually, frost fairs became mini festivals, a spectacle of shops, games, drinking, feasting and revelry. A “carnival on the water”, according to 17th-century writer John Evelyn. Even royalty visited the fairs – with King Charles II picking up this keepsake on the ice in 1684.

A frost fair keepsake printed for King Charles.

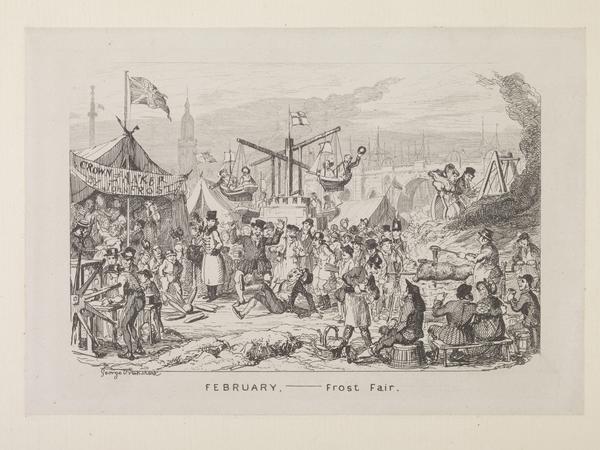

What could you do at frost fairs?

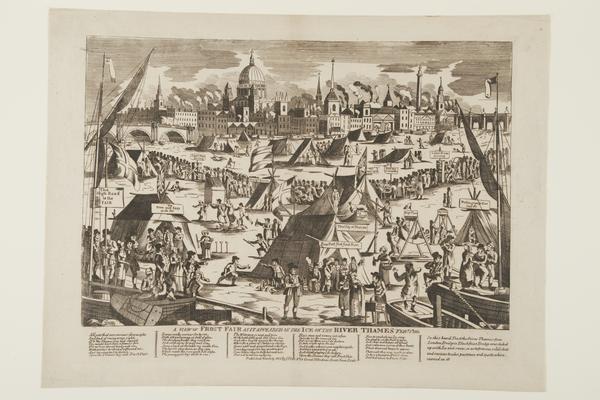

Well, what couldn’t you do at frost fairs? The print below is based on an engraving from 1685 detailing events at the spectacular, two-month long frost fair of 1683–1684. Londoners are shown hunting foxes, watching bull baiting and playing games like nine-pin bowling. The ice was even thick enough to roast animals over an open fire.

Sledging, sliding and skating over the ice was part of the fun of the fair. Londoners had long been keen ice skaters, and had skated on the city's frozen marshes and ponds for centuries. We have animal bone skates in our collection dating back to the 1100s.

And what could you buy there?

Tents and booths would be scattered across the Thames during frost fairs, featuring barbers, shoemakers, booksellers and traders selling food and drink. Imagine the relief of warming your hands with a hot cup of coffee in these freezing winters.

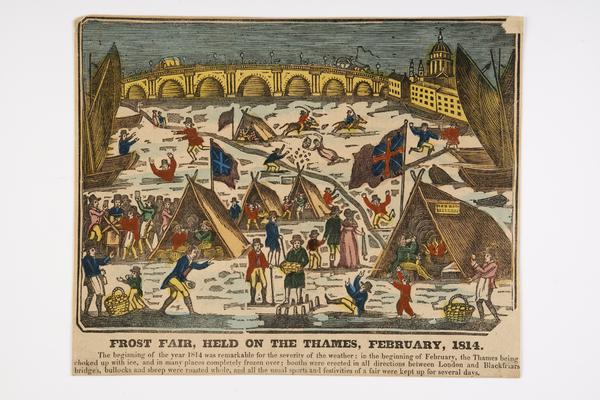

Others opted for something a little stronger – gin, rum, wine – at the temporary public houses. Some of these pubs had creative names, like The City of Moscow seen in this print from the 1814 fair – a comment on just how cold it had gotten in London.

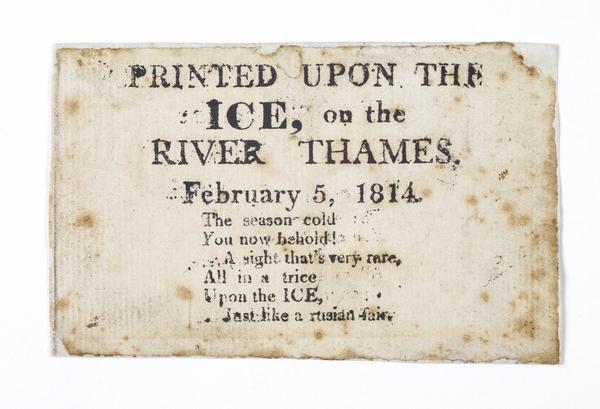

Printing shops were also a common sight. They sold souvenirs and keepsakes for a few pennies, as well as cards, ballads and leaflets. These could be personalised with your name and dated so you could remember your visit forever.

Why did frost fairs end?

The final frost fair in London took place in January 1814. The Little Ice Age ended in the second half of the 1800s, and as London’s climate began to warm up, these extremely cold winters became more infrequent.

A new, wider London Bridge with only five arches replaced the medieval crossing in 1831. And over the rest of the 19th century, the Thames was dredged and embankments had been built along more of the river edge.

Eventually, the River Thames had become too deep and too fast-flowing to fully freeze over again. And the fun of frost fairs were consigned to history.

Researching credit: based on a blog by Fabrizio Selli