Frances Burney’s mahogany desk: A symbol of slavery

Author Frances Burney supported the abolition of slavery. But her writing desk in our collection is tightly linked to the history of the British trade in enslaved Africans. How do we make sense of this contradiction?

1752–1840

A product of enslavement and colonial exploitation

Durable, warm-toned and able to take a high polish, mahogany was the fashionable wood of choice in 18th-century Britain. It was found in both royal palaces and the homes of London’s merchants and professional classes. Including that of novelist and letter writer Frances Burney.

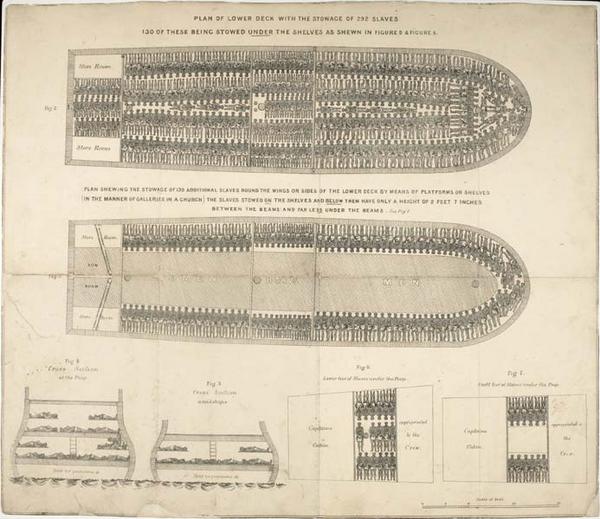

But across the Atlantic ocean in the Caribbean, those mahogany trees were being felled by logging gangs of enslaved Africans and contracted labourers. And the deforestation of islands like Jamaica caused by mahogany logging cleared land for vast sugar plantations, which became the foundation of the West Indian slave economy.

Burney’s mahogany writing desk – on which she wrote letters in favour of abolishing slavery – is a symbol of this disturbing history.

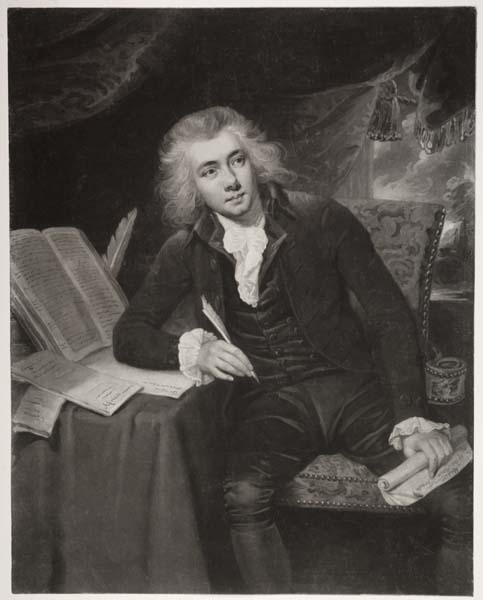

Frances Burney.

The desk’s royal origins

Burney’s mahogany writing box, or portable ‘writing desk’, was given to her by Queen Charlotte.

In 1786, Burney took up employment at the royal court as a ‘keeper of the robes’, or a dresser, to the queen. Her novels Evelina (1778) and Cecilia (1782) had been published to great success. So she accepted the position as a means of securing some financial and social independence from her family. She found the work dull, but developed a genuine friendship with the queen and her daughters.

“Burney must have spent many hours with this item”

As a prolific diarist and letter-writer, as well as a novelist and playwright, Burney must have spent many hours with this item. Despite being a gift from the queen, it’s a simple and un-showy piece with no embellishment other than plain brass fixtures. This was well suited to Burney, whose own taste was for ‘simple elegance’, and also to Queen Charlotte, who was as frugal as her royal status would allow.

A simple luxury object

Unfolded, the box transforms into a sloped writing surface, lined in dark green velvet, with compartments for holding an inkwell, quill pens and a supply of paper. There’s also an integral drawer, in which correspondence could be stored.

Underneath one of the compartment lids is a paper label, indicating that the box was made and sold by T. Knott, a stationer and bookseller at 361 Oxford Street, next to the fashionable Pantheon concert hall. On the corner of the label is a small notice: “Mahogany writing desks from 12 shillings upwards”.

At the time, 12 shillings constituted the best part of a week’s wages for a skilled labourer or artisan, and a month’s wages for a live-in servant. It might appear simple, but a box such as this one was a luxury object.

In one sense, there is nothing unusual about someone like Burney owning this box. She was a genteel and educated woman who was paid a salary of £200 a year by the queen – around £26,000 today. Burney was also paid for her writing and was certainly financially comfortable at this stage of her life. As she mixed with the most noted cultural celebrities of 18th-century London, she was well aware of what was considered fashionable in design.

But the desk was created from slave labour

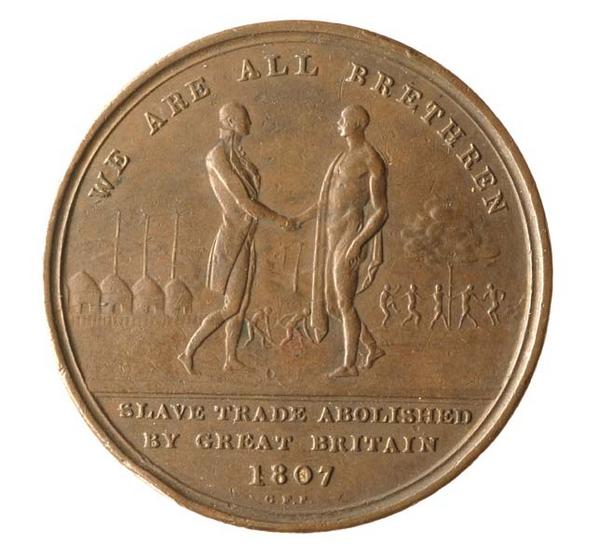

We know from her letters that Burney was in favour of abolishing slavery. And yet she owned and used something that was ultimately created from slave labour.

Committed abolitionists began to boycott West Indian sugar in the late 1780s in order to undermine the profits of the British trade in enslaved Africans. But this movement didn’t become widespread for several years.

There was no movement to abolish the use of mahogany at the same time. This was partly because the centre of mahogany logging had shifted from British-controlled Jamaica to Spanish-controlled Honduras. The logging was still undertaken by enslaved people.

Systems of enslavement and exploitation shaped life in Britain

Fundamentally, the ripple effect of the trade of enslaved Africans affected virtually every type of economic activity in 18th-century Britain. Even people opposed to slavery were likely to consume products produced by the system of enslavement and colonial exploitation. This could be directly as raw materials, or indirectly from trade networks and the accumulation of capital.

Products made from this system of global exploitation included mahogany, tobacco, cotton, sugar, spices, coffee and indigo dyes. These gradually became accessible to a broad middle class as the system expanded its reach.

Prominent abolition campaigners were entangled in these systems. Take the mahogany-veneered Buxton Table on display in London Museum Docklands, for example. It originally belonged to the abolitionist member of Parliament Thomas Fowell Buxton. And it was the table on which Buxton, William Wilberforce and their allies drafted the 1833 bill to abolish slavery throughout the British empire.

Frances Burney, around 1780.

Burney’s writing criticised – but also reinforced – hierarchies of race

While Burney isn’t really remembered as an abolitionist writer, she was well aware of the cruelties of slavery. In her last novel, The Wanderer (1814), the protagonist Juliet is a young white woman who wears blackface as a disguise in order to escape from revolutionary France. The categorisation of racial identity, and the racist hierarchy that privileged whiteness over blackness, had their origins in 18th-century scientific discourse. And it is this categorisation that supposedly justified the enslavement of African people.

As the secret of Juliet’s whiteness is gradually revealed, Burney writes that she moves ‘up’ the racial hierarchy. The novel’s other characters react in ways that demonstrate the racist and colonial thinking of the time. Once she presents as a white woman, she is eventually perceived as ‘refined’ and ‘civilised’ by the same people who wished to reject her as a black woman.

The Wanderer is a complex novel. It criticises the hierarchies and categories of race without ever fully breaking away from them. What’s apparent, though, are the disturbing parallels between the perception of people of African descent, and the perception of the raw materials grown and harvested by enslaved Africans: ‘rough’, ‘uncivilised’, ‘rude’ and ‘raw’.

Slave-grown sugar had to be refined, and slave-forested mahogany had to be polished, before it could be consumed and enjoyed by so-called ‘refined’ and ‘polished’ white Europeans. Contained within an object like Frances Burney’s mahogany writing desk is a global history of pain and exploitation.