Where did Tudor Londoners eat out?

And what did they eat? Whether grabbing a meat pie to-go or dining at a tavern or inn, 16th-century London had many places to eat outside the home.

Across London

1485–1603

Meat for the masses

Think of food in Tudor London and it’s perhaps the vast, spectacular banquets of King Henry VIII at Hampton Court Palace that first spring to mind. But what did your average Tudor Londoner actually eat, and where did they eat it?

Eating outside the home was crucial to Tudor citizens’ wellbeing and social life. Most Londoners didn’t have the facilities to cook hot food at home, be it an oven, a kitchen or the equipment for roasting or baking over a hearth.

Over the course of the 1500s, the city’s population quickly expanded from around 33,000 to about 250,000. Feeding this ever-growing city, where rich and poor lived in close quarters, required a mixture of establishments catering to different classes and tastes.

Cookshops

The Tudor version of a fast food joint. Londoners had been grabbing hot, ready-to-eat, takeaway food from cookshops since at least the 1100s.

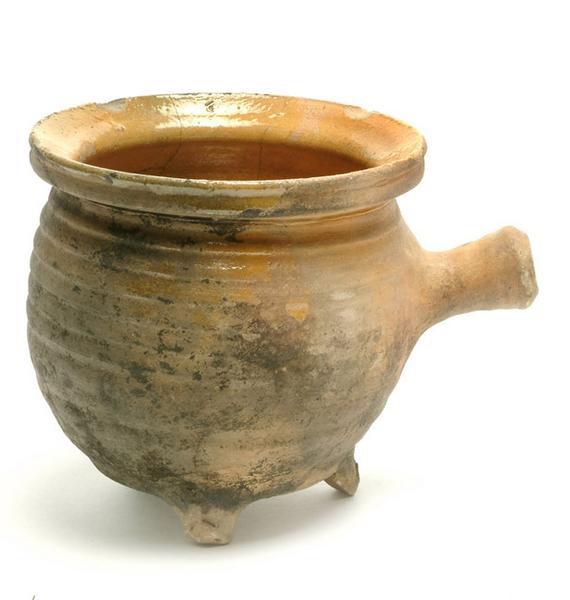

Cookshops were essentially big commercial ovens serving meat and fish. They first sprung up around the wharves and docks of the city, but went on to play a key role in feeding cityfolk, particularly the many poor Londoners living in cramped housing without cooking facilities. They were very popular, despite complaints about poor quality food and bad hygiene.

We don’t know much about the kinds of meals Tudor cookshops dished out, or the clients that ate them. There’s plenty of documents recording upper-class dining habits, but little for the poor and lower classes.

But we can look at sources like Joris Hoefnagel’s painting A Fete at Bermondsey for clues. See the meat roasting on a large fire as fat drips into the pans below, and large pies carried on pewter plates to hungry customers.

Alehouses

What did alehouses sell? Well, the clue’s in the name. Ale, a type of beer made with an infusion of malt, was the drink of choice in Tudor England. A more alcoholic version that was mixed with hops became increasingly popular from the mid-1500s. But it was said to “make a man fatte, and doth inflate the belly”.

“Snacks like spiced buns and cakes steeped in ale, as well as bread and cheese, helped soak up the booze”

By 1613, the City of London had over 1,000 licensed alehouses stocking a variety of beers and ales. Most of these were just a single room – and sometimes were located in the ale-sellers own house. They were thought to attract a poorer and rougher crowd. Women could also visit alehouses, but you’d only find those from the lower classes doing so without an escort.

Much like cookshops, alehouses also provided cheap food. Snacks like spiced buns and cakes steeped in ale, as well as bread and cheese, helped soak up the booze. Roasted meats were also served at lunchtime.

Inns and taverns

Where the alehouses were for the poor, the upper and middle classes went to the grander – and more costly – options like taverns and inns.

By the time of the Tudors, some of London’s establishments were offering a more varied menu than the typical meat, bread and cheese. England’s trade stretched across the globe, which brought in new products and influenced people’s tastes. This was reflected in the cosmopolitan cuisines found in its eating spots. Writing of a stay at a London inn in 1562, Italian visitor Alessandro Magno delighted in the choice of roast meats and pies, fish, fruit tarts, cheese and “excellent wine” on offer.

Livery company feasts

Livery companies like the Grocers, Fishmongers and Goldsmiths were responsible for the regulation of a specific trade. And to practice a trade within the City of London walls, you had to belong to one. But that wasn’t the only benefit. They also hosted pretty magnificent dinners in the company’s hall that thousands of Londoners must have attended.

“it is almost impossible to believe that they could eat so much meat in one City alone”

Alessandro Magno, 1562

The menus for these livery company feasts could be very wide-ranging. The account and dinner books for the Drapers, who managed the City’s cloth trade, included 139 different products across the second half of the 16th century.

Most dinner menus were meat based. The sheer range of different animals available led Magno to remark: “it is almost impossible to believe that they could eat so much meat in one City alone.” Fish, particularly sturgeon and pike, took second place in the ranking of feast-food-importance. You wouldn’t find many vegetables on the menu (perhaps they weren’t considered special enough), but seasonal fruit was there in abundance.

William Brooke, 10th Baron Cobham, with his family at a dining table.

Street sellers

Want a quick bite to eat on the go? You’d need to find a ‘hawker’. These street sellers worked the streets serving rich and poor alike.

Hawkers sold all sorts: fresh fruit, shellfish, baked apples, pancakes, eel pies, spiced gingerbread and the bygone London delicacy of boiled sheep’s feet. ‘Green meates’, another name for vegetables, were also readily available on a hawker’s cart. These began to be eaten more widely by both the wealthy and poor in the latter part of the 16th century.