fabric: A nightclub for a new millennium

In 1999, a new club named fabric opened in an underground Victorian meat warehouse in Smithfield, on the outskirts of central London. It’s now one of the capital’s leading venues – and London Museum’s nightclub in residence.

Smithfield

22 October 1999

fabric, 77A Charterhouse Street.

A crown jewel of London clubbing

Most of us who’ve been to fabric can, probably, remember our first time descending down those twisting stairs. The dark pit of Room 1. Metal against brick. A wall of sound. Floor vibrating. The disorientation of it all.

fabric opened in Smithfield in October 1999. This was the decade of the superclub – and the superstar DJ. But co-founders Keith Reilly and Cameron Leslie wanted a venue that took things back to basics: friendly hospitality, a top-notch soundsystem and a music policy that set the trends, rather than followed them.

The club was built in a 19th-century underground warehouse that once served the neighbouring Smithfield Market, the soon-to-be home of our new museum. It’s now one of the country’s best nightclubs with a reputation for excellence that draws in ravers from all over the world.

The fabric team in the late 1990s.

fabric was a reaction to the London club scene

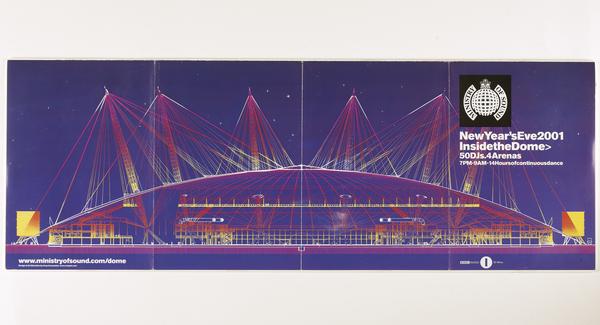

Nightlife in 90s Britain had been shifted by the arrival of massive superclubs like London’s Ministry of Sound and Liverpool’s Cream. Electronic music splintered into different scenes and styles. But it was house, trance and techno that had hit the charts. A circuit of celebrity-esque DJs raked in huge fees touring the country and overseas. Club culture in the capital had become a powerful and profitable industry.

“London had been taken over by the most ghastly, garish mutation of what we thought was ours,” recalled fabric co-founder Keith Reilly, who’d put on warehouse raves in the late 1970s. “It was a complete distortion of everything that was beautiful about this music. All of a sudden, venues were more interested in what shoes and shirt you were wearing than music policy. It was heartbreaking to me.”

“fabric was always intended to be a legitimised warehouse party”

Keith Reilly, 2009

The idea for fabric came from a reaction to the dominance of commercialised dance music and superclub culture. Reilly sold his CD and cassette manufacturing business – plus two family homes – to secure a venue to make it a reality. The perfect site? A warehouse at 77A Charterhouse Street, in an industrial area of central London, next to the nearly 1000-year-old Smithfield Market.

Print from 1811 titled A Bird's Eye View of Smithfield Market.

Taking over the cold stores of Smithfield Market

In the 1860s, Smithfield Market changed from selling livestock to storing, packing and selling meat to shops and restaurants. Underground refrigerated warehouses called cold stores were built to store meat imported to London before it was sold in the market. The previous occupant at 77A Charterhouse Street, Metropolitan Cold Stores, was one such warehouse.

When Reilly first found this dark and cavernous cellar, it had sat empty for almost 20 years. Smithfield in the 90s had a feel of industry in decline, a bit-run down. But “fabric was always intended to be a legitimised warehouse party,” he told Resident Advisor in 2009. “I wanted it to feel like you've gone to an industrial zone, and you're in an old disused building.”

Fitting out the new fabric

It took two years of structural work and renovations to transform this Victorian underworld into a nightclub. fabric has three rooms of music accessed via a maze of bars, stairs and chillout areas. It’s big, too – over 2,250 square metres of space. The unisex loos, constructed out of a hardy flame-treated steel, were also a point of interest.

A month before fabric was due to launch, a big and flashy new club called Home flung open its doors in central London’s Leicester Square. Paul Oakenfold – the world-famous trance DJ and producer – was the resident. Of course, this didn’t concern the fabric crew. They were after a different sound and a different crowd.

fabric’s sound system – and vibrating dance floor

The whole club was designed around its sound system, the vision of leading sound and lighting engineer Dave Parry. There are tens of speakers each for different frequencies – subwoofers for low-end bass, compression drivers for those "ntz ntz" highs. These are controlled digitally and the sound can be "moved" across the dance floor using 3D modelling.

“you actually feel the music, as well as hear it”

But the showpiece? Room 1’s "bodysonic" dance floor, the first in Europe. There are 450 tactile transducers – speaker devices that ‘shake’ with the bass – under the dance floor. So you actually feel the music, as well as hear it.

No expense was spared, and the job wasn’t done when the doors first opened. They replaced the original system just one year in with a crisp, powerful Martin Audio one that came to define the club’s sound and legacy. It was only upgraded in 2024.

Poster for Friday night's fabriclive parties from 2001.

fabric opens to the public on 22 October 1999

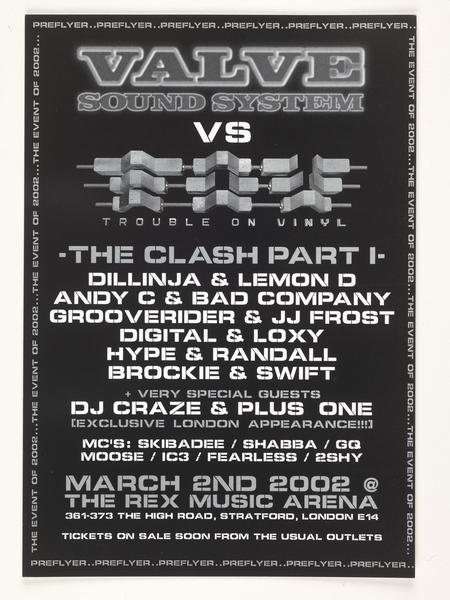

fabric’s opening lineups laid down their intention. Their first public night was a drum and bass party, which set the routine for Fridays being in the realm of all sounds bass-heavy. Crowds lined right down Charterhouse street. It was a roadblock.

Ravers also heard the club’s resident DJs, Craig Richards and Terry Francis. They were talented friends of Reilly’s, but back then somewhat unsung heroes of the underground. They’ve been a staple of the club’s Saturday nights ever since.