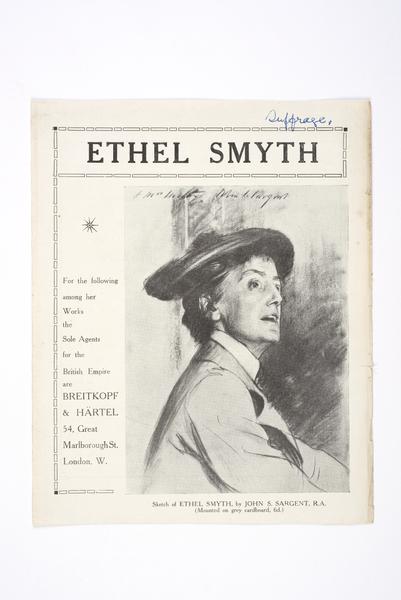

Ethel Smyth: Composer & Suffragette

Ethel Smyth was a composer who became a close friend of Emmeline Pankhurst, joined the Suffragette movement and composed their protest anthem. She’s an important queer figure in London’s history.

Sidcup, Bexley

1858–1944

Musical activism

Ethel Smyth’s prodigious career as a composer earned her an international reputation. In 1903, she broke ground as the first woman to ever have her music performed at The Metropolitan Opera in New York City.

In London, however, she earned a second legacy as a member of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). She invested her talents and passion in the Suffragettes’ votes for women campaign – and even went to prison for the cause.

Her activism and her music, which earned her a damehood, are described in her published memoirs. These memoirs also reveal her romantic relationships with women. They’re a valuable record of queer experience from a time when the views of society forced many to live in secrecy.

Smyth’s composing career and legacy

Smyth was born in 1858 in Sidcup, south-east London. She was raised at a time when male composers dominated the music profession and the creativity and skills of women were undervalued and ignored. This prejudice dogged Smyth throughout her professional life, but she rebelled against it to achieve great things.

In spite of Smyth’s critics, in 1888 the famous Russian composer Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky stated: “Miss Smyth… can seriously [be considered] to be achieving something valuable in the field of musical creation.” Her music and operas were performed in Britain, Europe and the USA. In 1910, the University of Durham awarded her an honorary doctorate of music.

Her music has begun to be recognised in modern times. Smyth’s The Wreckers – described in the Guardian as a “long-neglected maelstrom of an opera” – was performed at Glyndebourne Festival in 2022.

Becoming a Suffragette

After hearing the Suffragette leader Emmeline Pankhurst address a meeting at the home of the writer Anna Brassey, Smyth decided to join the Women’s Social and Political Union in their fight for women’s right to vote. Smyth formally signed up in 1910, taking a two-year break from her career to become an activist.

She got to know Pankhurst well, which Smyth described as “the fiery inception of what was to become the deepest and closest of friendships”.

“from the first my most ardent sentiments were bestowed on members of my own sex”

Ethel Smyth, Impressions that Remained, 1919

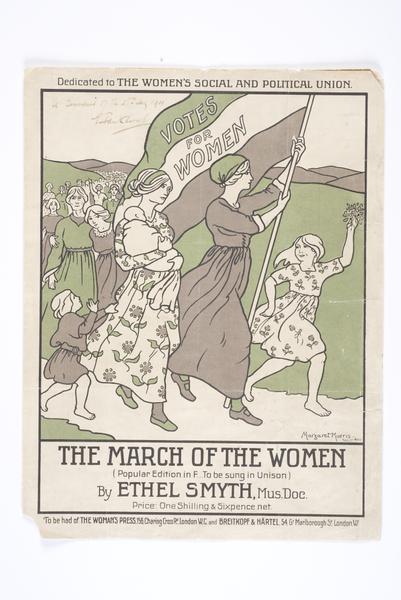

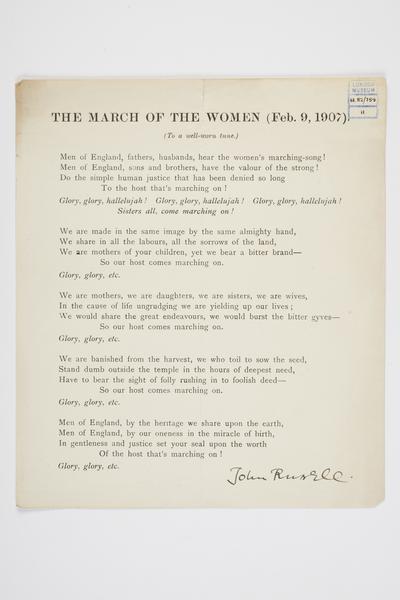

The March of the Women

The March of the Women was composed by Smyth in 1911. A handwritten copy is one of several items related to Smyth preserved here at London Museum.

It was first played on 21 January 1911 to welcome the release of Suffragettes imprisoned after a Black Friday protest in November 1910. The song quickly became the most popular protest anthem of the movement.

Described as a hymn and a rousing battle cry for the Suffragettes, The March of the Women inspired women to take militant action.

Processions of Suffragettes carried cards printed with the music and accompanying lyrics by writer and activist Cecily Hamilton. Members of the public became familiar with the piece after witnessing these marches.

In 1911, the WSPU presented Smyth with a commemorative baton for empowering the organisation and raising its profile.

Prison time

Despite being 54, with a respectable background and groundbreaking professional reputation, Smyth was not spared a prison sentence for her Suffragette militancy.

With around 150 women, Smyth participated in the window-smashing campaign of March 1912. Alongside Emmeline Pankhurst, Smyth targeted the secretary of state for the colonies, Lewis Harcourt, who’d made comments against the votes for women campaign. The pair found his office at the Houses of Parliament and broke the windows.

For this, Smyth spent time in Holloway Prison, surrounded by her fellow imprisoned Suffragettes. Emmeline Pankhurst’s cell was next door.

Even prison failed to stifle Smyth’s spirit. On a visit in 1912, composer Thomas Beecham saw Smyth rallying the other imprisoned women:

“I arrived in the main courtyard of the prison to find the noble company of martyrs marching round it and singing lustily their war-chant while the composer, beaming approbation from an overlooking upper window, beat time in almost Bacchic frenzy with a toothbrush.”

After prison

Prison records tell us that Smyth was released early from her sentence, citing the strain on her mental health.

She went to her home in Woking, Surrey, and was followed there by Pankhurst, who’d been released to recover from her hunger strike.

A photograph of the pair together can be seen in our collection, dated 26 May 1913, as the police arrive at Smyth’s home to re-arrest Pankhurst. We see Pankhurst, weakened by her hunger strike, supported on Smyth’s lap. Smyth is holding an umbrella to shelter Pankhurst from the sun.

Emmeline Pankhurst during her re-arrest on 26 May 1913, being supported on Smyth’s lap.

Memoirs of loving women

Following her involvement with the Suffragettes, Dame Ethel Smyth published a flurry of memoirs which give us greater insight into Smyth’s romantic life.

At that time, women and queer people were discouraged from revealing the details of their sexuality in public. This tends to hurt LGBTQ+ people today as they look for their legacy in London’s history.

But Smyth had many female lovers and was inspiringly open about documenting her feelings for women.

As early as 1892, she had written to a male friend that “it is so much easier for me, and I believe a great many English women, to love my own sex more passionately than yours.”

Some people have suggested that Emmeline Pankhurst’s relationship with Smyth was romantic. A lack of conclusive evidence means we can’t be sure.

Aged 71, Smyth met the writer Virginia Woolf, and later declared: “I don’t think I have ever cared for anyone more profoundly.” Woolf wrote in her diary that Smyth loved her, but that she didn’t feel the same way.

Ethel Smyth was knighted

In spite of challenging the government through her activism, and her groundbreaking, unconventional life, Dame Ethel Smyth was knighted as a Commander of the British Empire in 1922. She became the first woman to be granted the damehood for her contributions to composition and publication.

This is an edited version of a blog by Andrew Millar, Host