Early modern London’s sewage problems

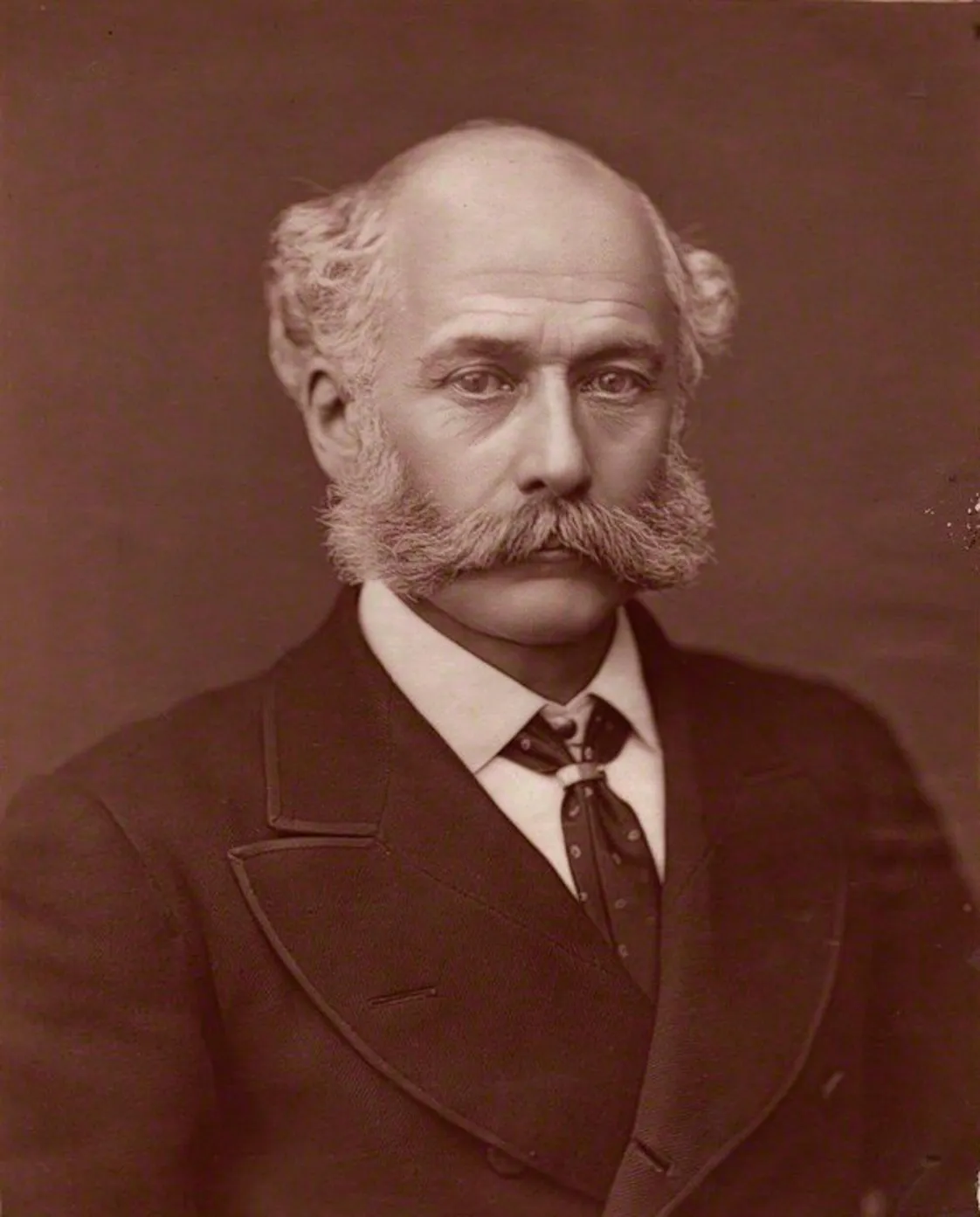

Before the 19th century, when Bazalgette’s sewers delivered London from the Great Stink, Londoners had to live through the stench of cesspits and chamber pots – and the bitter arguments these caused.

City of London and Southwark

1400–1700

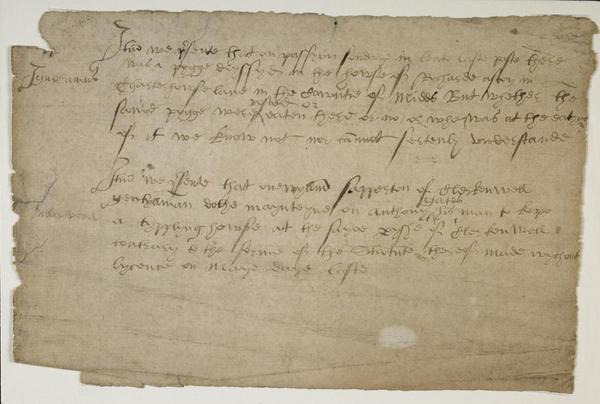

A 17th-century bedpan or chamber pot, for night-time nature calls.

A noxious stink

On 20 October 1660, the famous diarist Samuel Pepys had a nasty surprise when he opened his cellar door and stepped into a “great heap of turds” which had overflowed from his neighbour’s toilet.

Pepys’ problem was not uncommon. This was a time before waste could be flushed far out of sight at the push of a button.

Records from London show that sewage issues were a major cause of legal battles and neighbourly disputes.

Chamber pots – used by people doing their business at night – were emptied into the streets. Cesspits were placed too close to shared walls, seeping through the brickwork and rotting timbers. Pipes, ditches and streams were blocked with animal dung, human waste and rubbish. The situation stank.

“going down my cellar to look, I put my foot into a great heap of turds…”

Samuel Pepys, 1660

Legal disputes

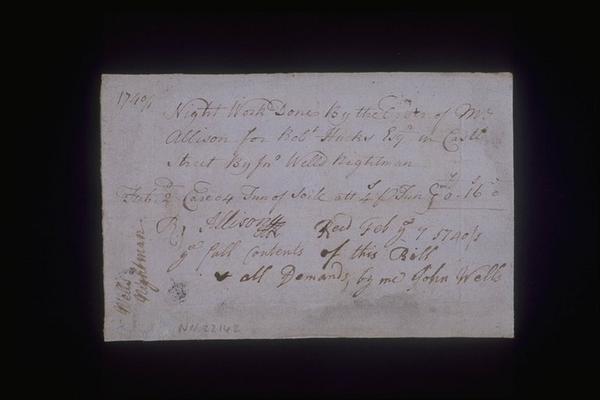

Before modern sewers, toilets often fed into a cesspit, a hole dug into the ground to collect the waste. Over time the cesspit would fill up, until it was emptied by nightmen – a name given because they worked at night to protect people from the stink.

In 1328, William Sprot complained that the cesspit of his neighbours Adam and William Merre was too near his building. It was so full of sewage that it had penetrated his stone wall and entered his house “and collects there, causing a great stench”.

Most of the cases brought to the attention of the authorities were the result of overcrowding, changes to buildings and neglect. But occasionally people were accused of deliberate bad behaviour.

In 1314, Alice Wade was disciplined for casting “the filth of her privy into the common gutter” so that it became a “vile nuisance” to all of the neighbours.

In 1400, textile worker Robert Asshecombe took action against his neighbours who failed to maintain the walls around their communal toilet, exposing their “private business” and wafting “evil odours”.

In 1613 Jane and Charles Browne of Whitechapel, east London were arrested “for emptying a great quantity of night-work into the common sewer to the general annoyance of all the inhabitants”. The couple were placed in the stocks in Artillery Lane, Spitalfields for six hours – a punishment which involved being locked up by your feet in a public place.

Private toilets were rare

Part of the problem for Londoners was the lack of private places to go. In 1579, the 85 residents of All Hallows, close to the Tower of London, had just three private toilets between them.

Many people were forced to use the public toilets which were dotted around the city.

The wealthiest households had their own garderobes – an inside toilet – but they were often still shared between the people in the house, and it often fed into a cesspit shared with other houses.

In our collection, we have a medieval toilet seat which was found in Ludgate Hill, in the City of London. But it’s not quite what you’d expect. The seat has three holes, so that three members of the same household could sit alongside each other. Cosy.

Who took responsibility for the sewage?

Following City tradition, men “cleansed their jakes according to their falls by even portion”. In other words, the upkeep and cleaning of toilets and cesspits was shared between those who used them.

But where toilets all fed into the same cesspit, which household was responsible for maintaining the plumbing and the cost of emptying the cesspit? Which family had to face having the filth carried through their house?

Not surprisingly, responsibility for the upkeep of cesspits and toilets was taken very seriously. People left money for the care of toilets in their wills. And the city authorities tried to ensure that they were correctly built, maintained, regularly cleaned and emptied at night.

Chamber pots: a new toilet trend

Starting in the mid-16th century, chamber pots – or “bed pots” – began to be used by anyone needing to pee or poo during the night. They needed emptying each morning – into a nearby cesspit, a stream or, often, the street.

Silver chamber pots are occasionally listed among the household items of the rich, but the majority were made from pewter or ceramic.

Chamber pots in our collection

We have quite an impressive collection of 16th- and 17th-century chamber pots here at London Museum.

Several were dug out of old cesspits, dropped by mistake or dumped with other household waste. A few have traces of the pee and poo they once held.

When archaeologists uncover these cesspits, they sometimes still stink of rotting matter. One, used by people living in Frying Pan Alley in Southwark, was found in a layer of the cesspit containing the remains of fruits and seeds, which may have been eaten to help with digestive problems like constipation.

The collection includes several late 17th-century examples of tin-glazed earthenware chamberpots – a style known as delftware – made in Southwark at the Montague Close or Pickleherring potteries.

Another group, made in Harlow, Essex, are decorated with slip – coloured liquid clay – and feature messages such as “Be Merry and Wise”, “Fear God Honour the King” and “break me not I pray in your hast for I to non will give destast, 1663”.