Dub in London: Shops, sound systems & legends

Dub reggae is part of London’s musical identity. After landing here in the 1970s, a thriving scene formed around the city’s record shops, sound systems, labels and producers.

Across London

Since the 1970s

Dub runs deep in London

Dub music emerged in Jamaica in the late 1960s, and imported Jamaican records soon found an audience among young Black Caribbean Londoners whose families had been invited to Britain as part of the Windrush Generation.

Played at parties, clubs and carnival, dub became popular with white working-class listeners too, and fused with other genres, like punk.

In the 1970s, dub records began to be made in London and exported around the world. To this day London has a busy dub scene – one you’d find it hard to miss at Notting Hill Carnival.

What is dub?

Dub, or dub reggae, is an offshoot of reggae, where the studio itself is used as an instrument to create a unique sound.

Producers are the stars of dub, using their equipment to manipulate recordings. The emphasis is on the drums and bass, and producers add echo and reverb to give a hypnotic, stretched-out feel.

“It’s the bassline you know, as it hits you, it pushes out all negativity”

Sistah Stella

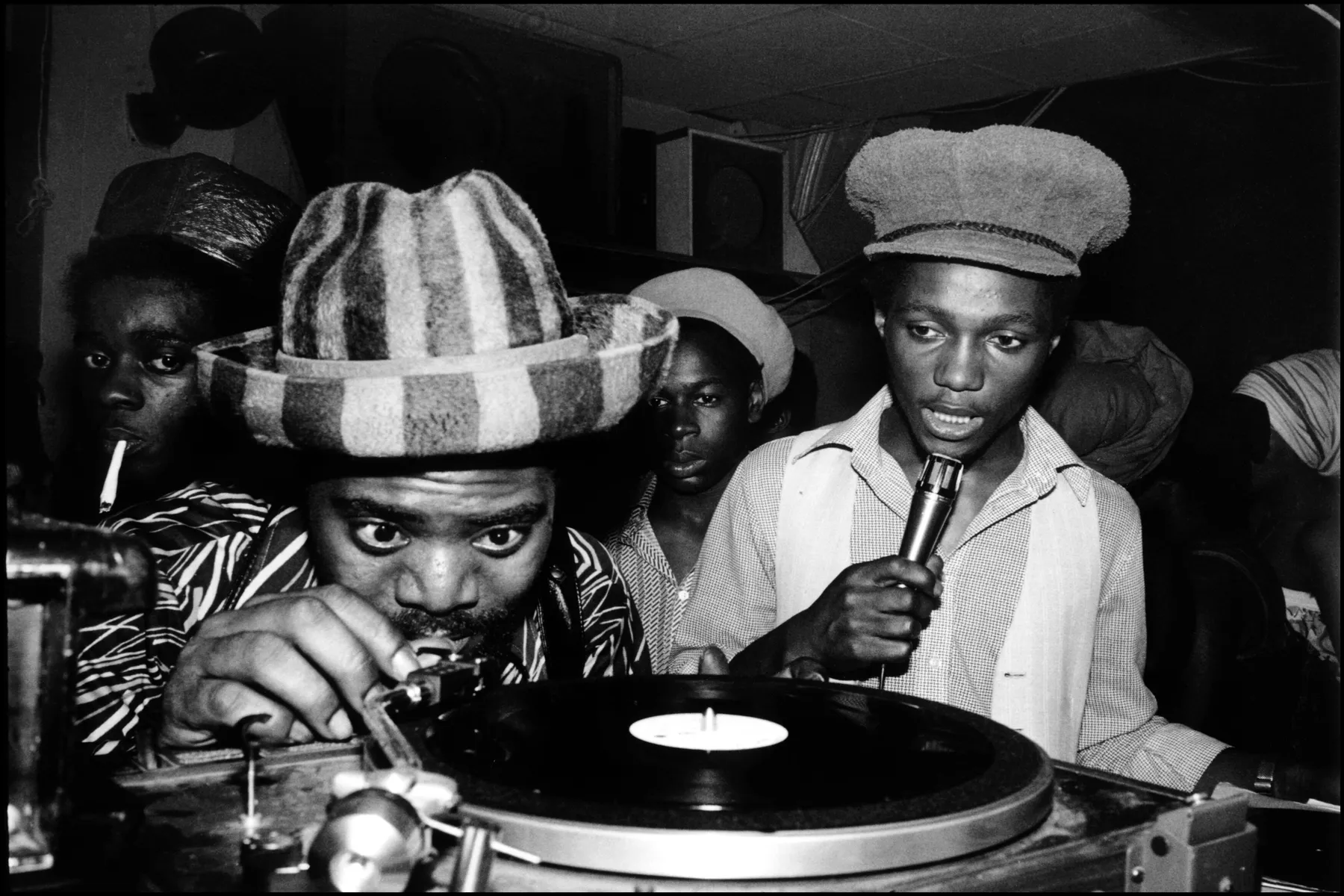

Dub was often created from the instrumental B-sides of reggae records – sometimes just called a “version”. When played out by sound systems, those instrumental versions allow MCs to “toast” over the track. Dub tracks soon replaced the straightforward B-side instrumental.

“The A-side of a record would awaken me to social commentary which spoke of politics, race, class, humanity, justice and injustice, of love and of sorrow!” says Sistah Stella of Rastafari Movement UK. “But it was the B-side of dub that gave me a profoundly deeper inner, almost electric surge of strength. It’s the bassline you know, as it hits you, it pushes out all negativity”.

Dub’s studio-built beats – perfect for an MC – influenced the creation of other British genres, including jungle, UK garage and grime.

Duke Vin

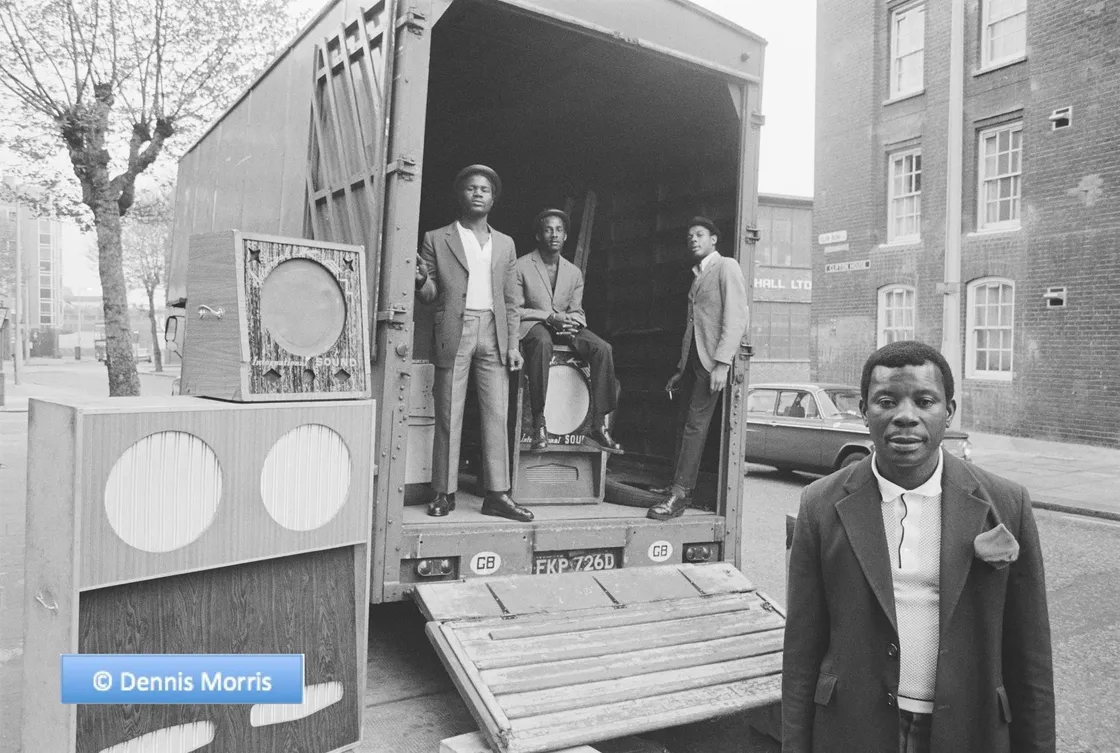

Sound systems began in Jamaica as mobile discos – hand-made speaker arrangements taken from party to party playing the latest records. In 1955, Duke Vin introduced them to Britain.

Vincent Forbes brought the first sound system to Britain.

As a boy in Kingston, Vincent Forbes had been a record selector. When he came to England, he set up a basic sound system and began playing Jamaican reggae and ska at house parties around Ladbroke Grove in west London.

He helped make Jamaican music popular at a time when it wasn’t played on British radio. Vin played at Soho’s Flaming Club and the West End Marquee Club, and performed at Notting Hill Carnival for 37 years.

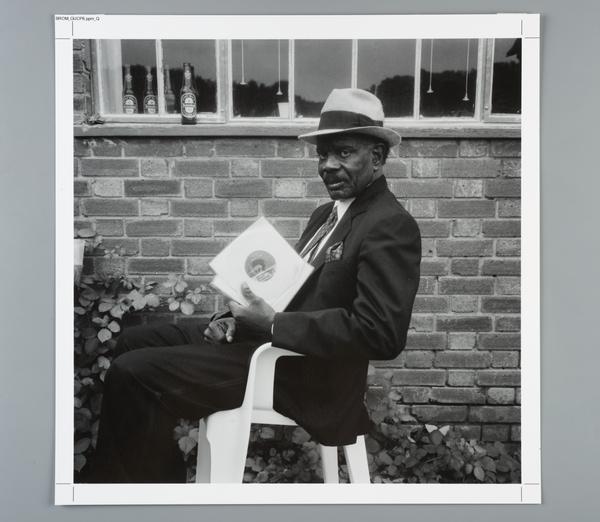

Admiral Ken

Ken Edwards or “Admiral Ken” was a well-known sound system operator and nightclub owner in the 1970s, who appeared at house parties in Hackney and clubs like the Four Aces in Dalston. His nightclubs – including Palace Pavilion club, or “Dougie’s”, on Lower Clapton Road – attracted major reggae artists.

Admiral Ken often performed with the trio shown in the photo: boxer Dennis Andries, DJ “Henry” and toaster Frederick Howell.

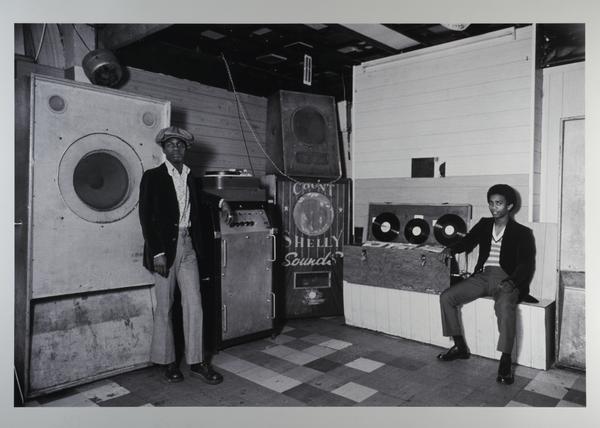

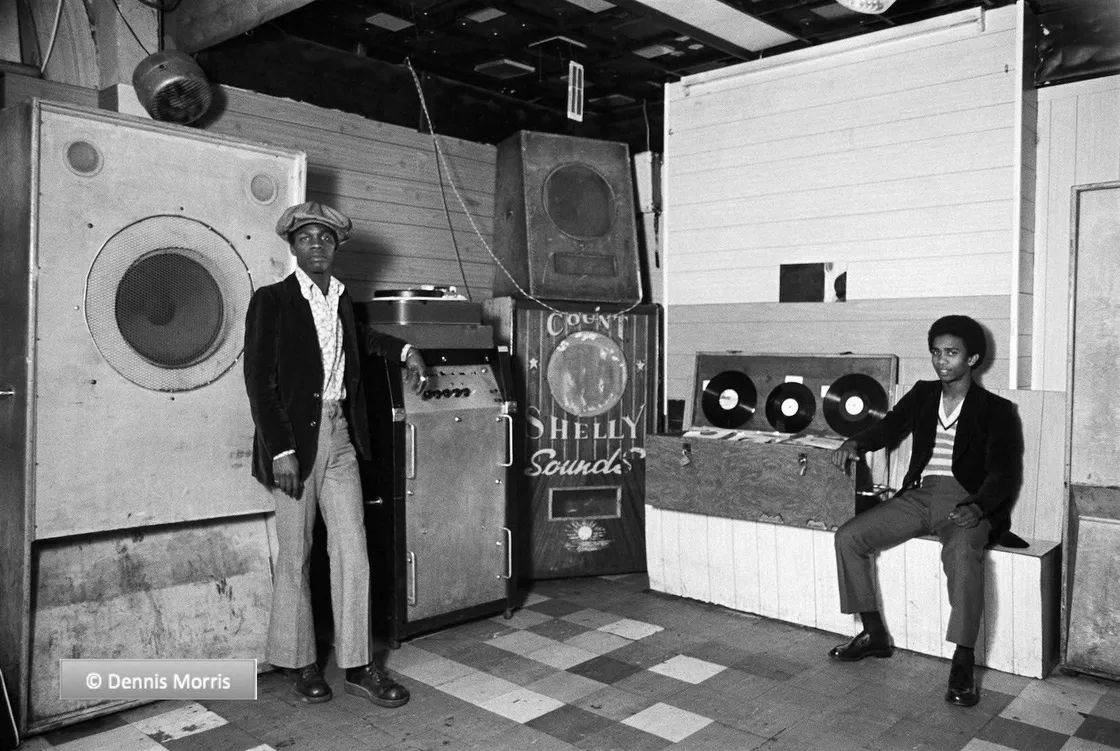

Count Shelly

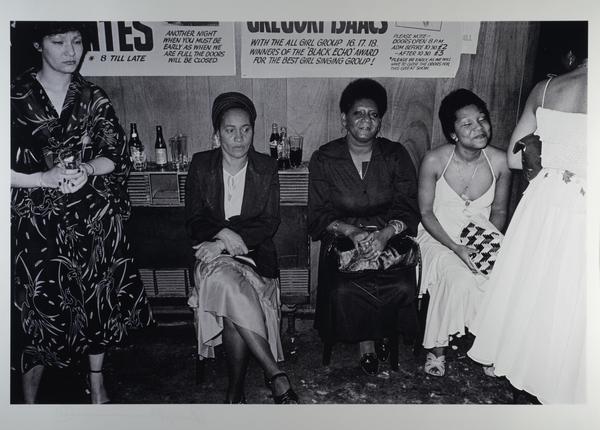

Count Shelly was a pioneering sound system operator and record producer based in Hackney. At the time of this photograph, Count Shelly was a resident DJ at the Four Aces in Dalston, which hosted clashes between sound systems. According to the photographer Dennis Morris, the Four Aces was “for the big boys, big men. To go there you had to be tough.”

Ephraim Barret or ‘Count Shelly’ at the Four Aces Club, Dalston in 1973.

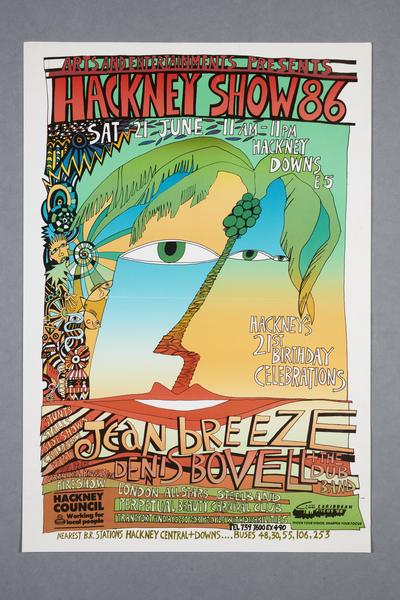

Dennis Bovell

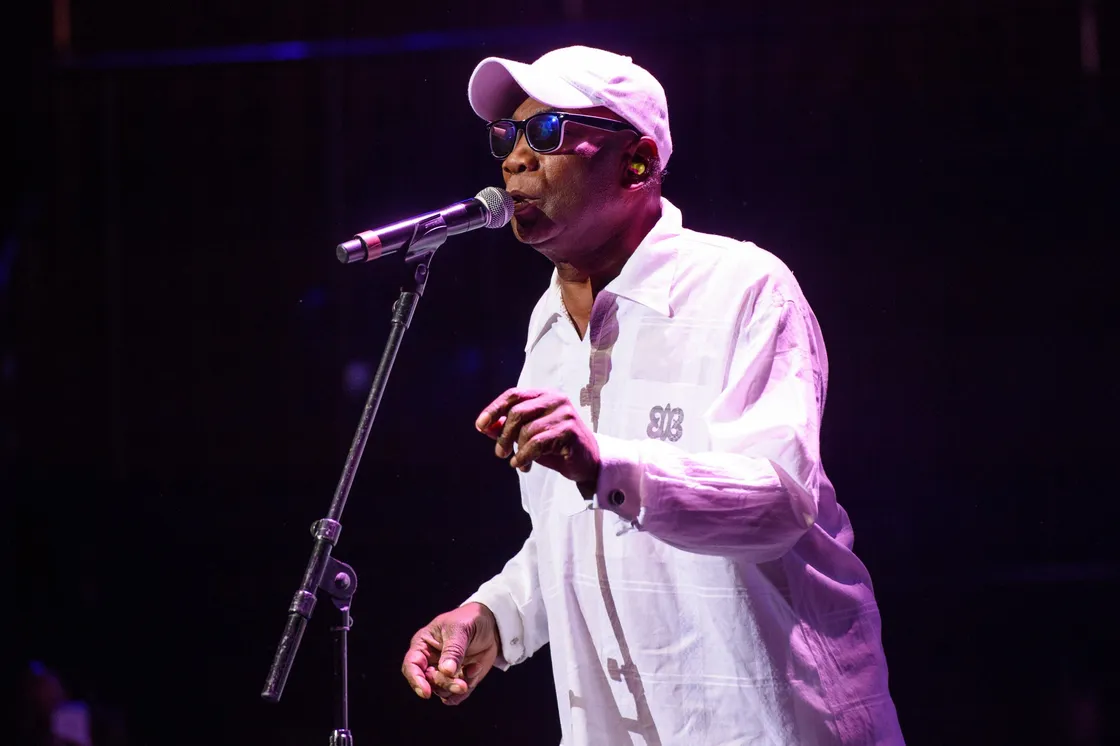

Dub’s most famous artists are King Tubby and Lee Scratch Perry – two producers who created the genre in Jamaica. But London has its own heroes, and Dennis Bovell is one of them.

Dennis Bovell, UK dub legend.

Bovell was born in Barbados in 1953, came to London in 1965, and first stepped into a music studio at his school in Wandsworth, south London.

Bovell was the Sufferer sound system’s DJ in the 1970s, and later formed the group Matumbi. He produced Janet Kay’s lover’s rock classic Silly Games and music by dub poet Linton Kwesi Johnson. As well as pure dub releases, his other output fused dub with different genres, as on The Slits’ punk masterpiece The Cut.

Mad Professor

Neil Fraser – known as the Mad Professor – is another of London’s great dub artists. After he left school in the late 1970s, he set up his first studio in Thornton Heath, Croydon, south London.

His albums from the 1980s, released on his own label Ariwa, are full of unpredictable instrumental journeys, and make an excellent introduction to the sound of dub. He’s collaborated with Massive Attack, Linton Kwesi Johnson and Sly and Robbie.

Mad Professor, a lynchpin of London's dub scene.

Dub and reggae record stores

London’s dub scene relies on a network of iconic dub and reggae record stores, many of which have run for decades.

Dub Vendor’s flagship store in Clapham Junction first opened in 1982, with DJ Papa Face behind the counter. That store’s gone now, but Papa Face is still involved. Supertone Records in Brixton, south London was opened by owner Wally B in 1984. And Peckings, in Shepherd’s Bush, west London, was opened in 1973 by George “Peckings” Price. He’s said to be the first person to have brought Jamaican music to Britain.

Record shops were a key meeting place – the spot to hear new records shipped in from Jamaica, and a place for music-obsessed Black Londoners to connect with that part of their identity.

At first, Dub Vendor’s success relied on getting new records from Jamaica only a week after their release. But this changed as British artists made dub their own. British-based artists began to produce their own dub in the 1970s, as well as variations like lover’s rock – a softer, distinctly British sound.

Channel One Sound System

Run by Mikey Dread, Jah T and Ras Kayleb, Channel One’s sound system has been a cornerstone of Notting Hill Carnival since 1983.

The carnival first featured sound systems in 1973 to attract young Londoners who were big fans of the dub and reggae they played.

But sound systems had been around much longer, used to provide the tunes at clubs, unofficial “blues dances”, and shebeens (unlicensed pubs). In the 1950s and 1960s Black Londoners’ gatherings often had to take place in houses or unofficial venues because of the racism they faced on the street.