The City of London’s last lollipop lady

What’s bright and eye-catching but becoming harder to find on the streets of London? School crossing patrol officers – known to most as lollipop ladies.

Since 1950

Stopping traffic and saving lives

Do you regularly pass a lollipop man or woman on your journey? Their high-vis outfits mean you’ll know if you do, but over the last 20 years they’ve become a rarer sight.

These unsung heroes help protect children as they cross the road on their way to school – and London boroughs were instrumental in popularising the job.

From the 1950s, they’ve been a fixture of our streets. Today, their bright yellow uniforms and lollipop-shaped signs are familiar to generations of Londoners.

That’s why the uniform of one important lollipop lady – the last in the City of London – is here at London Museum.

Gallagher's uniform, now in our collection, complete with hat and lollipop sign.

Sheila Gallagher

This uniform was worn by Sheila Gallagher MBE, the last lollipop lady to work in the City of London.

Born in Holborn in 1924, Sheila Gallagher lived in London her whole life, working in the City since leaving school.

From 1991 to 2010, Gallagher was a school crossing patrol officer for the City of London School for Boys. She supervised the pedestrian crossing where Peter's Hill crosses Queen Victoria Street, just south of St Paul’s Cathedral.

A greatly loved member of the school community, she was known for her “friendly character and winning smile”.

In 2004 London’s mayor Ken Livingstone thanked her “for making an outstanding contribution to life in London”. She was awarded the MBE by Queen Elizabeth II for her service to the community.

For many years Gallagher was the only lollipop lady in the City of London. She became the last when the introduction of a push-button crossing made her role redundant. She died in 2015 at the age of 90.

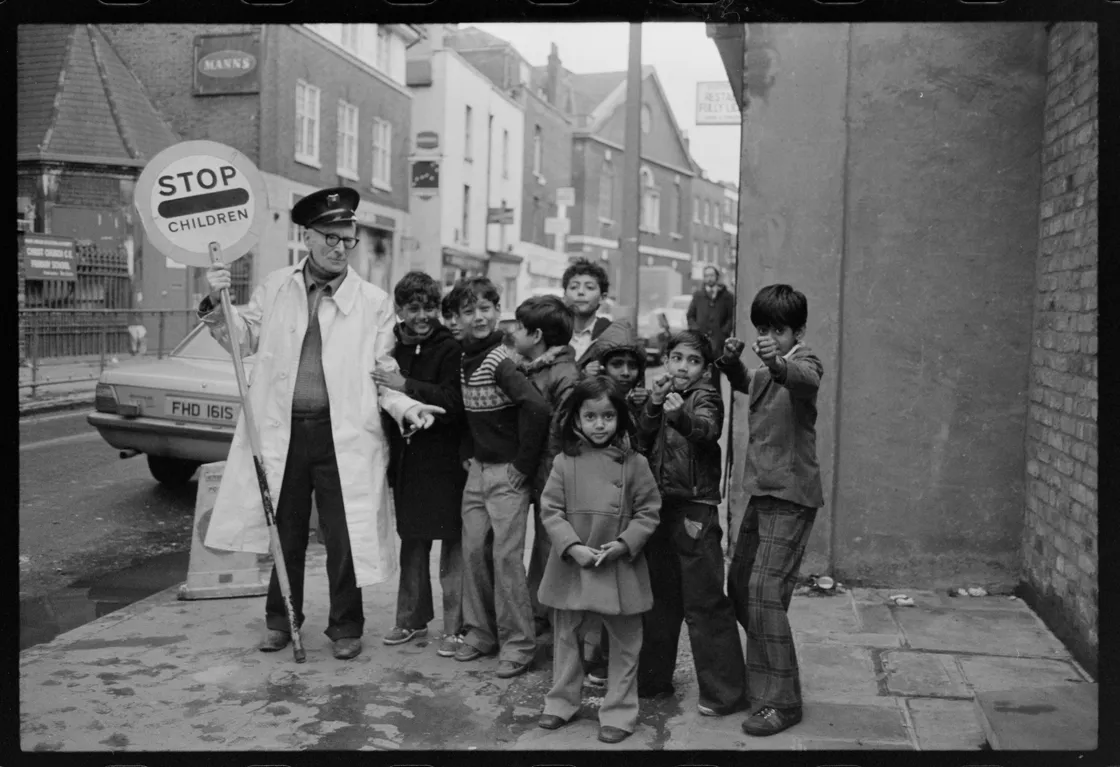

Gallagher on duty at her Peter's Hill crossing.

Who was the first lollipop lady?

The first British school crossing patrol officer was Mary Hunt. In September 1937, Bath City Council chose this school caretaker to help pupils cross the road.

However, lollipop men and women are arguably a London invention. After the Second World War ended in 1945, progress in London led to patrols becoming widely adopted.

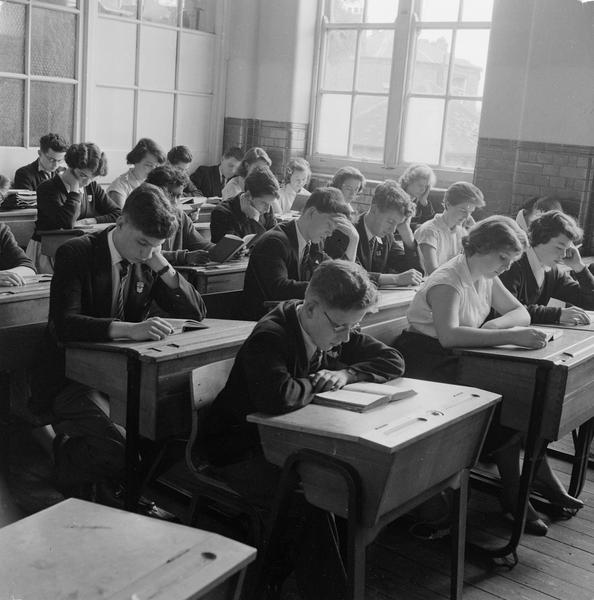

Two of Britain’s first road safety officers – Dorothy Pummell for Barking borough, and Jock Brining for Dagenham borough – were horrified by the number of road accidents involving children. At that time 90% of children walked to school unaccompanied.

As a trial, Pummell and Brining recruited “able-bodied pensioners” to help schoolchildren cross the road, issuing them with a lollipop sign, white coats, yellow armbands and peaked caps.

“The round lollipop was introduced in the 1960s”

Lollipop laws

Other boroughs followed suit. The patrols were recognised officially with the introduction of The School Crossing Patrol Service in the 1950s by the Metropolitan Police. This was part of The London Traffic (Children Crossing Traffic Notices) Law of 1952.

The act allowed anyone authorised by the Commissioner of the Metropolitan Police, and using the correct sign, to stop traffic in order to allow children to cross. Traffic had to stop before reaching the patrol or be fined £5.

The 1953 School Crossing Patrol Act extended the idea nationally. Since then patrols have been granted the right to stop traffic and to escort adult pedestrians across the road as well as children.

Costume change

While the first patrols were made up of men, the “lollipop lady” and her distinctive uniform became a common sight outside schools across the country. Many became much-loved figures within their community.

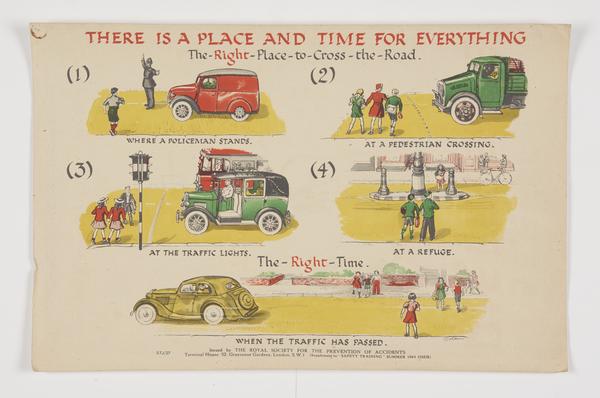

The earliest lollipop signs were red and black rectangles printed with “Stop, Children Crossing”.

The round lollipop was introduced in the 1960s and the uniform changed to the familiar yellow coat in 1974.

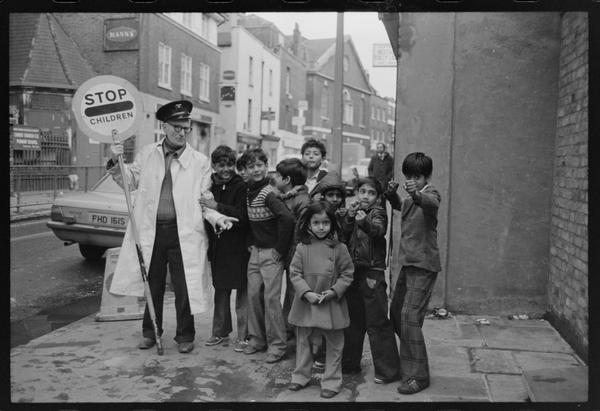

A lollipop man on Brick Lane, Spitalfields in 1979.

Disappearing lollipop ladies

The legal requirement to provide patrols was removed in 2000. Combined with budget cuts for local authorities this means there are now fewer on our streets. Across Great Britain, the number of council-funded patrol officers fell by 22% between 2013 and 2018.

Remaining posts are difficult to fill due to the short hours, low pay and aggressive behaviour from motorists.