Charles Dickens’ ‘Memoirs of Joseph Grimaldi’

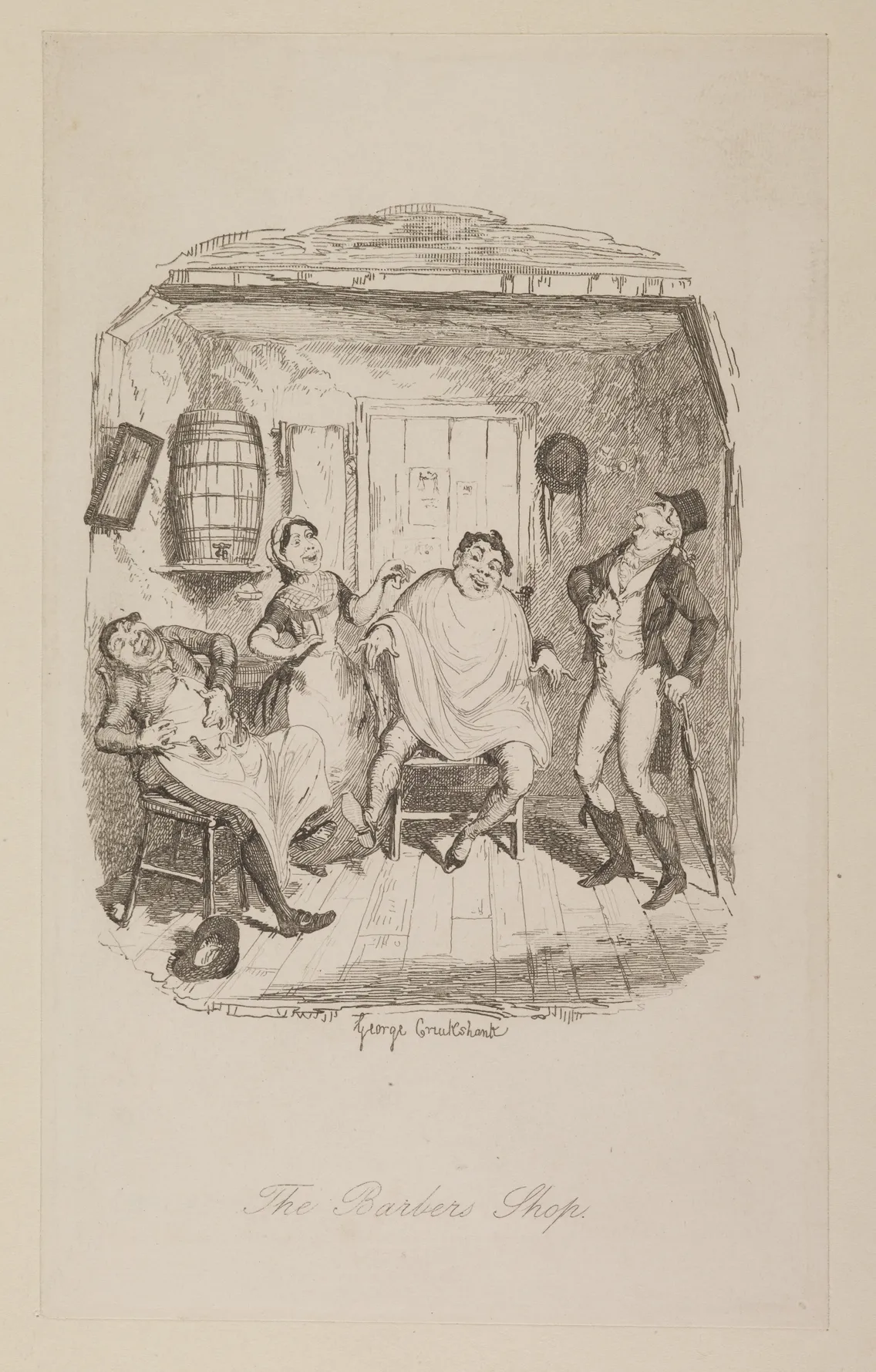

Joseph Grimaldi was London’s most famous clown. The highs and lows of his life were documented in his memoirs – edited by Charles Dickens, and illustrated by George Cruikshank.

1838

A story of laughter and misery

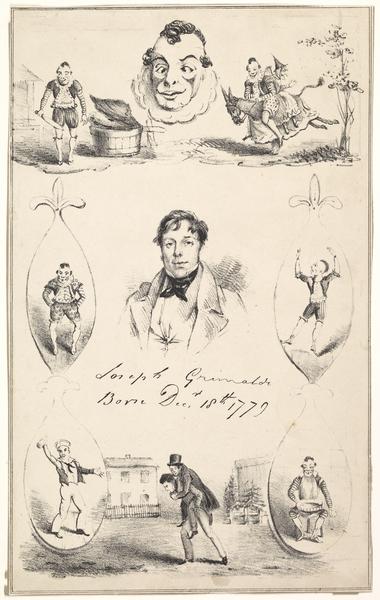

Credited as ‘the founding father of pantomime’, Joseph Grimaldi’s use of white face paint, colourful costumes and wild physical comedy made him the first ‘modern’ clown. But his onstage antics had a serious effect on his health. He died in 1837 aged 58.

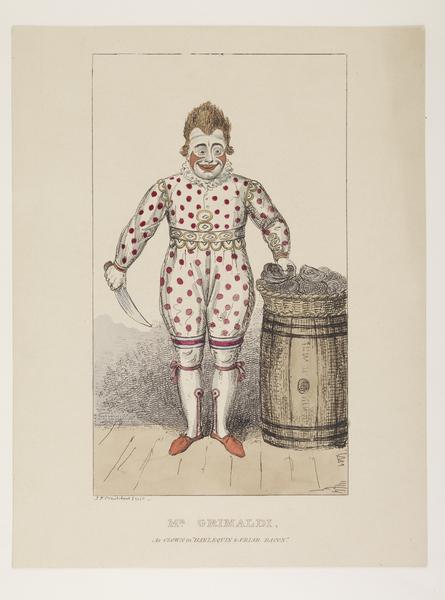

Author Charles Dickens was 25 years old – and relatively unknown – when he was asked to edit Grimaldi's journals. Memoirs of Joseph Grimaldi was published in 1838 under his pen name, Boz. Celebrated caricaturist and Dickens collaborator George Cruikshank did the illustrations.

It tells Grimaldi’s story in classic Dickensian style – contrasting the glitz of his life onstage with the hardships he endured off it.

Grimaldi’s unfinished memoir

Grimaldi had written down his memories in his retirement and asked journalist Thomas Egerton Wilks to edit the final manuscript. But after Grimaldi died, Wilks abandoned the work.

The new publisher, Richard Bentley, offered Dickens the editing job – but Dickens initially refused, despite being a big Grimaldi admirer. He'd seen Grimaldi at a Christmas pantomime when he was a boy.

“It is very badly done,” Dickens said to Bentley, “and so redolent of twaddle… I should… be assured three hundred pounds… without any reference to the sale.” Still, he changed his mind. Memoirs of Joseph Grimaldi was published in 1838.

Memoirs of Joseph Grimaldi edited by Charles Dickens and illustrated by George Cruikshank.

Using Grimaldi’s autobiographical notes, Dickens edited and, in parts, ghost-wrote the story from his birth to his retirement and eventual demise. The book includes 12 illustrations by celebrated caricaturist George Cruikshank. This reprinted edition was published in 1882–1883.

Dickens and Cruikshank: collaboration and conflict

Cruikshank began working with Dickens when he created the illustrations in Sketches by Boz, published 1836. Their collaboration was initially positive and successful, with Cruikshank illustrating Dickens’ hugely popular Oliver Twist.

But from the 1840s, their relationship soured over Cruikshank’s anti-alcohol stance (Dickens was himself a moderate drinker). And Dickens criticised Cruikshank’s moralistic rewriting of fairy tales.

In 1870, after Dickens’ death, Cruikshank even publicly claimed he came up with many of the ideas in Oliver Twist.

The most famous clown of his time

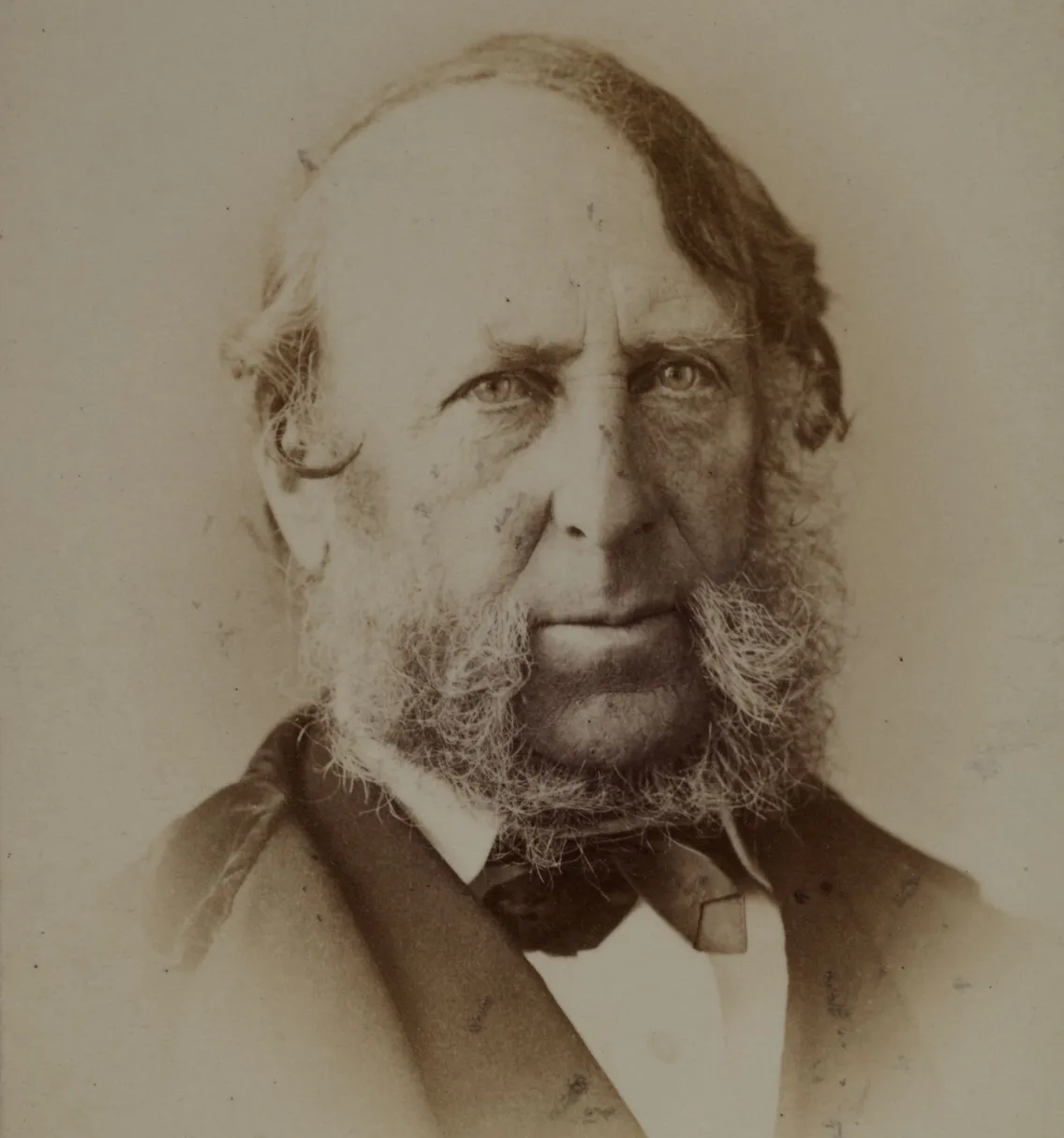

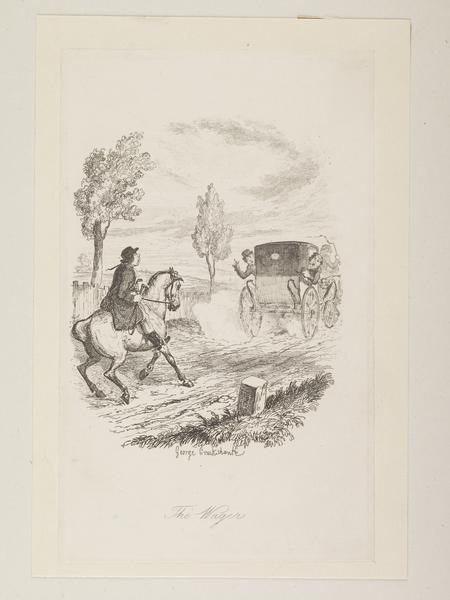

Memoirs is essentially a 19th-century celebrity biography – perhaps with less revelatory gossip than what we’d read today. It details Grimaldi’s soaring fame as London’s favourite clown. In one print, he’s shown being mobbed by a large crowd as he attempts to escape by jumping into a cab.

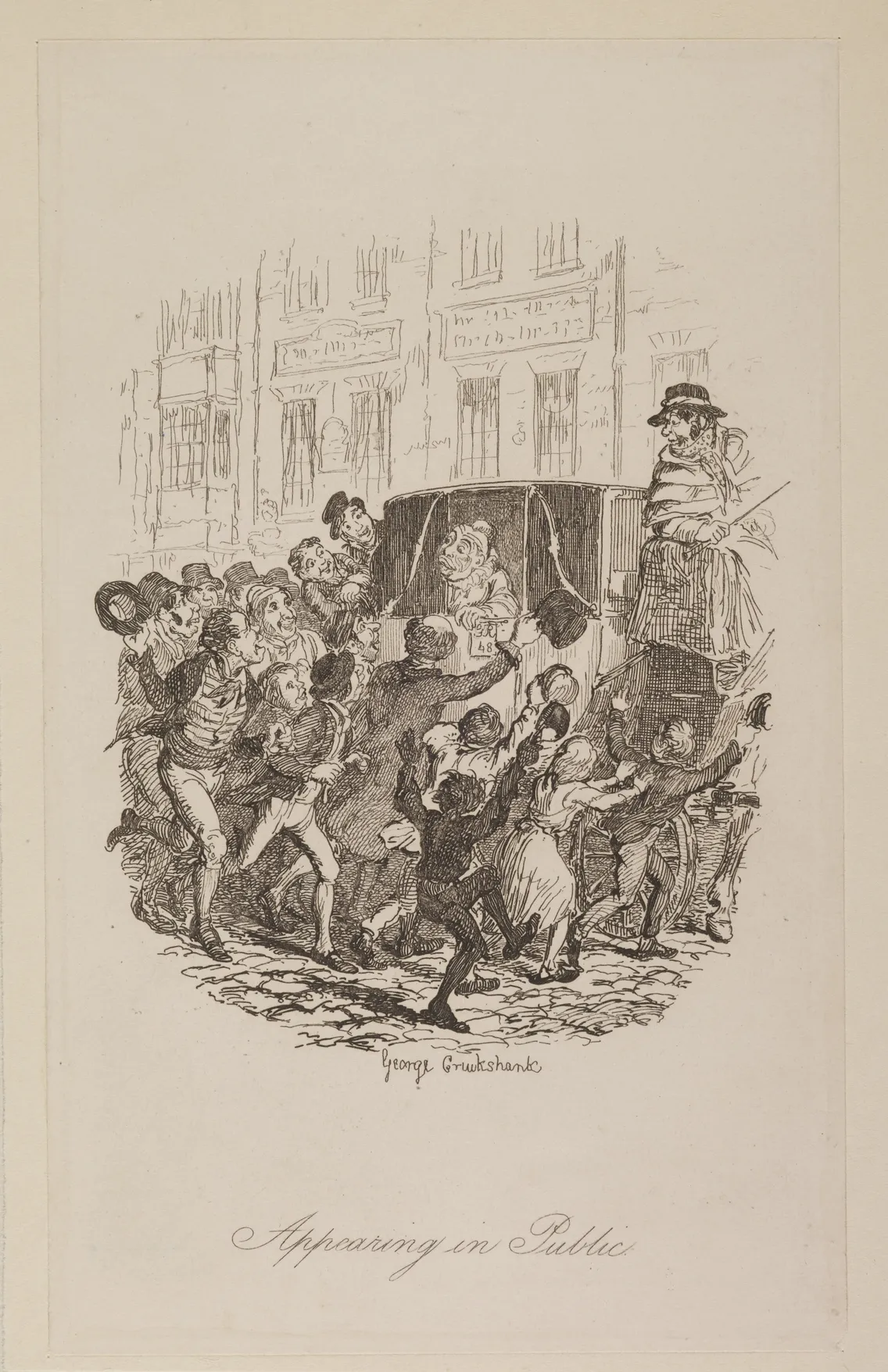

In another print, Grimaldi is depicted in a barber's shop. The barber's daughter had attempted to shave him. But Grimaldi found it so funny that he couldn’t stop laughing, making everyone around him laugh as well.

“there always seemed some odd connexion between his good and bad fortune”

Charles Dickens

An economy of pleasure and pain

In Memoirs, Dickens constantly balances Grimaldi’s success with equal doses of personal suffering.

“Throughout the whole of Grimaldi’s existence… there always seemed some odd connexion between his good and bad fortune,” he wrote. “No great pleasure appeared to come to him unaccompanied by some accident or mischance.”

Skim across the book’s contents and you’ll see “Dreadful Accident”, “Robbed by Highwaymen on Highgate Hill” and “Miserable Death of his Son” peppered among his many accomplishments. Dickens also describes Grimaldi’s deteriorating health in his later years as the result of his desire to please his audience.

This illustration, titled The Last Song, is on a page where Grimaldi is quoted saying "I have overleaped myself, and pay the penalty in an advanced old age".

His “attention to his duties and invariable punctuality were always remarkable”. But the “immense fatigue” caused by overwork “sowed the first seeds of that extreme debility and utter prostration of strength”. Dickens wrote this when he was 27 years old. Ironically, it came to mirror his own relentless attitude to work.

Cruikshank’s masterful work

Dickens later claimed that the Memoirs were published “chiefly to please” the illustrator Cruikshank. He wasn’t particularly proud of his own contribution. But he acknowledged that “the good right hand of George Cruikshank had seldom been better exercised than in his illustrations of Joseph Grimaldi.”