The calls of London’s historic street traders

You’ll often hear a street trader before you see them. Over the centuries, artists have captured the unique ways London’s hawkers drummed up business.

1600–1900

Selling out loud

In every noisy city, part of the cacophony comes from traders calling out for attention.

In Europe, artists in the 15th century began to draw street traders, recording their distinctive rhymes, songs and catchphrases in surveys which became known as “street cries”.

Our collection includes a number of these focused on London. Ranging from the 17th century through to the end of the 19th century, the images give a flavour of the city’s atmosphere, and help us understand what people were buying, selling, using and eating.

A 17th-century street trader sells second-hand fabric.

The earliest collection of street cries we have dates from 1688, by the artist Marcellus Laroon. His Cryes of the City of London was the first substantial series in this style, and was reprinted many times.

Laroon drew idealised types of traders, rather than basing his work on individuals. This woman is selling second-hand fabric, or as she says it: “Old Satten Old Taffety or Velvet”.

Two women selling oysters in the 18th century.

Jumping forward to 1760, artist Paul Sandby used a far more realistic style in his series Twelve London Cries of London done from the Life.

This print shows two women selling oysters, calling out "rare meltin' oysters". Now seen as a luxury, oysters were cheap enough in the 18th century to be a popular food for working-class people.

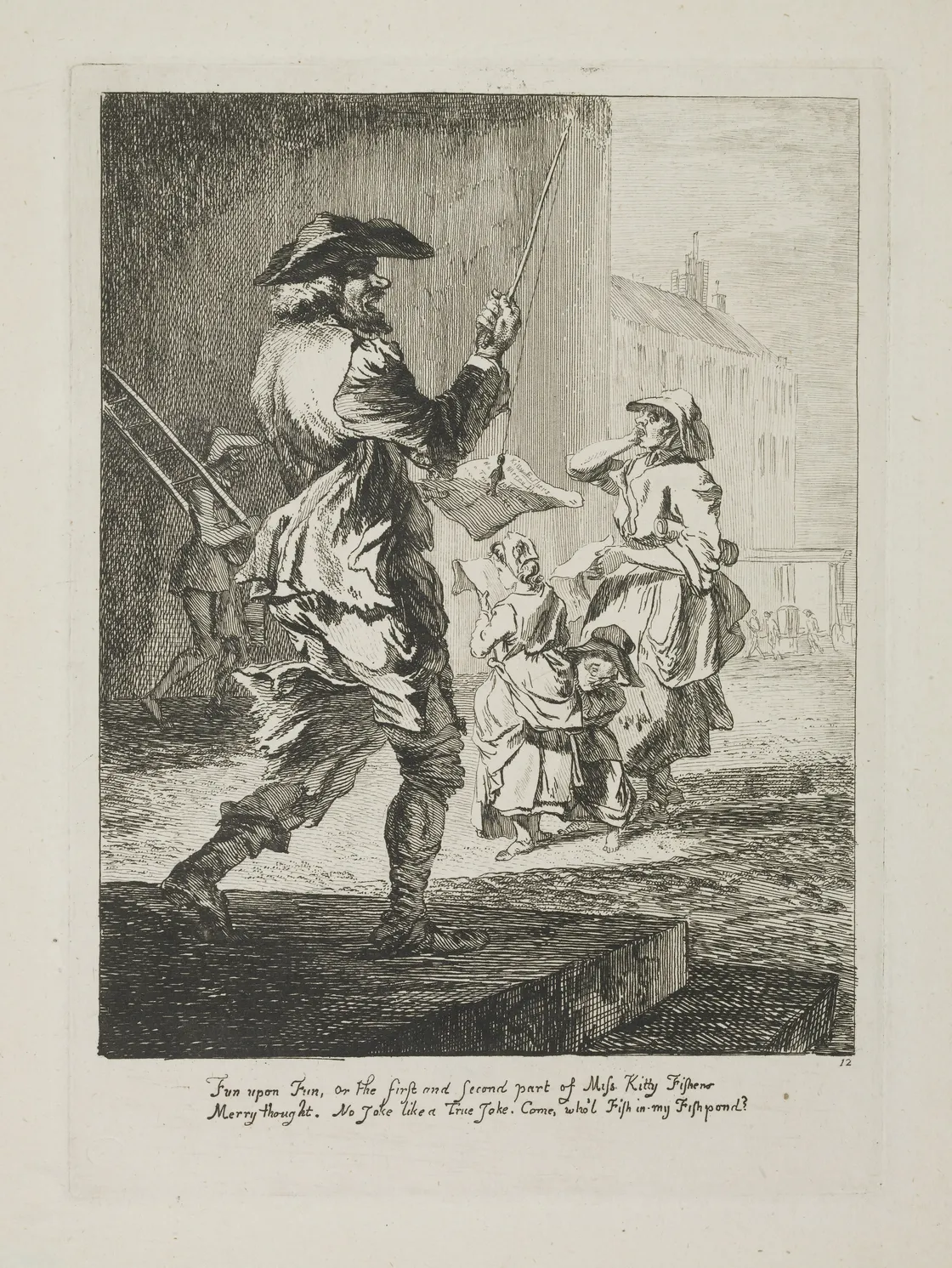

A husband and wife sell a ballad about Kitty Fisher.

Another print from Paul Sandby here. In this one, a man sells ballads – literally the printed lyrics to a song. Not something you could imagine nowadays, but in the 1700s it was a popular way to buy music.

The song being sold in Sandby’s drawing is about Kitty Fisher, a famous courtesan from the time who mixed among society’s elite. The ballad-seller’s wife sings the song to attract attention, featuring the line: "Who'll fish in my fish pond?"

A woman sells turnips and carrots in this Francis Wheatley engraving, with the caption "turnips and carrots oh".

Thirty years later, in the 1790s, Francis Wheatley exhibited his series of paintings, The Cries of London, at the Royal Academy. Like other popular paintings from the Royal Academy at this time, they were frequently reproduced as prints.

Wheatley’s paintings give an idealised view of London – everyone appears happy and healthy, with no sign of poverty or illness.

Thomas Rowlandson's 1799 comic sketch of a goose seller.

Satirist Thomas Rowlandson probably produced his 1799 series partly to mock Francis Wheatley’s romanticised depiction of London.

His images always have a comic element. "Buy my goose, my fat goose" says the seller, but the couple are disgusted – not so fresh, it seems.

A watercress seller, by Thomas Rowlandson.

Another in Rowlandson’s series shows a man on his way into a brothel – he’s interrupted by a woman and her children selling watercress: "Water cresses, come buy my water cresses".

Watercress sellers were some of the poorest of London’s street traders. Watercress grew in the streams and growing beds just outside the city, and would be picked and sold daily. Street sellers worked independently, buying it from London’s markets early in the morning.

A change of tradition

In the 19th century, the images of street traders began to appear in books. The tradition shifted more towards studying the living and working conditions of poor Londoners – with Henry Mayhew’s book, London Labour and the London Poor, as the prime example.

John Thomas Smith’s book The Cries of London was published in 1819. This picture shows “an industrious Irishman”. Children paid a halfpenny to pull a string, which made a doll’s head appear in one of the holes in his box. If they picked the right hole, they won a sweet biscuit, known as a gingerbread nut.

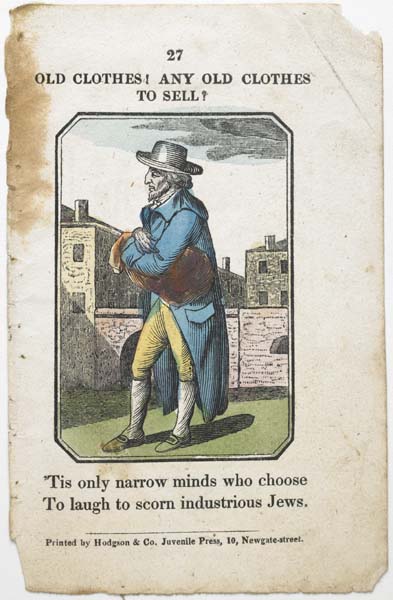

Two pages from a children's book featuring street traders from around 1845.

Cries of London made it into kids’ books too. This one, by J Bishop, is from around 1845. Its owner has signed the inside. Again, each page shows a different trader, and each is paired with a short poem.

These two pages show a match-seller and a broom-seller, who boasts that their brooms are made from hair, and free of whale bone.

This engraving of a "newsboy" selling papers in the City was printed with a poem.

This series of prints by William Nicholson isn’t strictly all about street sellers, but it’s a similar collection of London characters, or London Types, as he called it. All were accompanied by a short poem too.

Nicholson made these prints in the 1890s, using the coarse grained side of the wood block in a style taken from Japanese prints.