Boudica: Rebel queen of the Iceni

Boudica was queen of the East Anglian Iceni community. In the first century CE, she rebelled against Roman rule, attacking and burning London.

City of London

Unknown – 60 or 61 CE

This statue of Boudica riding her chariot is close to Westminster Bridge.

A queen’s rebellion

In the first century CE, London was a thriving Roman town, but not yet a capital. The Romans called it Londinium.

Around 60CE, it was attacked and burned as part of a rebellion led by Boudica. She did the same to Colchester and St Albans.

The queen and her followers were eventually defeated. But Boudica’s revolt has lived on as legend, with the queen entering folklore as a towering, red-headed patriotic warrior.

“very tall, in appearance most terrifying”

Cassius Dio

Who was Boudica?

Boudica was queen of the Iceni, a community living around Norfolk, eastern Cambridgeshire and northern Suffolk during the Iron Age and the Roman period.

Until recently her name was often spelled Boudicea, but we now know this was based on a historic mistake.

We only know anything about Boudica because of her revolt. Historians were still writing about it centuries afterwards. Which goes to show just how severe the Roman army’s losses were – even if the revolt was ultimately unsuccessful.

When they described Boudica, Roman historians used common misogynistic stereotypes about northern European women.

One, called Cassius Dio, describes her wearing a golden torc around her neck, and says she was “very tall, in appearance most terrifying… [with] a harsh voice, and with a great mass of the tawniest hair [which] fell to her hips”.

In Roman society, women were expected to look and behave a certain way. For these elite male writers, Boudica was the opposite.

Why did she rebel against the Romans?

By 60 CE, the Romans were 17 years into their conquest of Britain. Even with a huge army of 50,000 soldiers, it hadn’t been easy.

Boudica, who may have been around 30 then, would have spent most of her adult life surrounded by war and violence.

The remains of a Roman fort in the Lake District, in northern England.

The Romans relied on making allies to keep control – these local rulers were useful friends, until the Romans no longer needed them. The same method continued to be used by conquerors in modern times, including the British empire.

One of these disposable allies was Boudica’s husband, Prasutagus. When he died in 60 CE, he tried to leave his kingdom to his daughters and the Roman emperor Nero.

Instead, the Romans took full control, seizing the Iceni’s lands. Boudica was whipped, and her daughters were raped.

Boudica and the Iceni joined with another community of Britons called the Trinovantes and led a revolt against the Romans.

Boudica burning London

While the Roman governor was distracted in Wales, Boudica’s rebellion wreaked havoc.

Starting around 60 CE, Boudica and her followers first attacked the Roman town Camulodunum – now called Colchester – burning, stealing and slaughtering huge numbers of people. London was next. Buildings were burned, and people living there were killed.

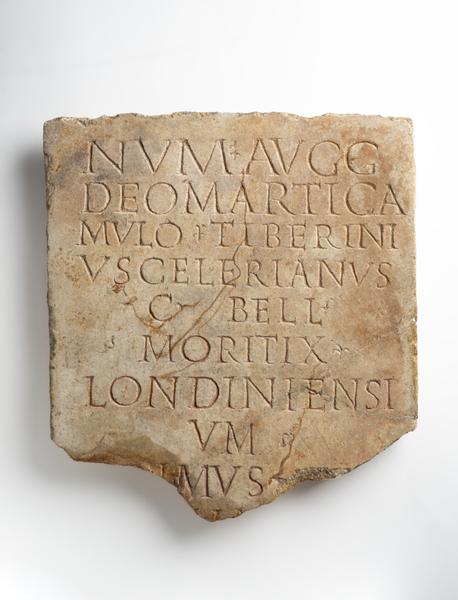

For proof that London was attacked, we don’t just have to rely on Roman writers. Our collection contains pottery and personal possessions from buildings burned down by Boudica’s army. In central London, archaeologists have found thick layers of burned debris. Burned finds from Colchester add to the evidence.

Our collection also includes four small carved gemstones – made to be set into rings – which were buried in Eastcheap, central London, at around the same time. One shows Pegasus. Another a discus thrower. They’re strong symbols of Roman culture – not something you’d wanted to be caught with by Boudica’s army. It’s very possible these items were hidden by whoever owned them.

After London, Boudica raided St Alban’s, then called Verulamium, repeating the burning, stealing and killing. In total her rebellion may have killed tens of thousands of people.

This ceramic container was buried to hide the carved gemstones inside, possibly during Boudica's rebellion.

How did Boudica die?

Boudica’s followers destroyed one Roman division sent to face her, but she couldn’t follow up on this victory.

The Romans regrouped with the remainder of their soldiers and marched to confront her on a battleground they had chosen.

A battle took place, probably somewhere in the midlands. Roman sources say that the Britons, led by Boudica, outnumbered the Romans.

But Boudica was defeated. One Roman historian says she poisoned herself after the defeat. Another says she died of illness. Poison is more likely – Boudica would have known that if the Romans captured her, she’d be humiliated, possibly paraded through Rome in chains, and finally executed.

An old story says that she’s buried under King’s Cross train station, but there’s no evidence for this. We don’t know where Boudica is buried.

This highly romanticised depiction of Boudica comes from a 19th-century book, the Illustrated History of England.

Boudica’s place in history

Boudica’s rebellion came genuinely close to booting the Romans out of Britain. Her story became a legend over the centuries, told by writers and poets from the 16th century, and more recently in films.

Boudica has been used as a patriotic symbol of leadership and defiance. A statue of Boudica and her daughters riding in a chariot, commissioned by Prince Albert, can be seen by Westminster Bridge.