Behind the scenes of post-war drag shows

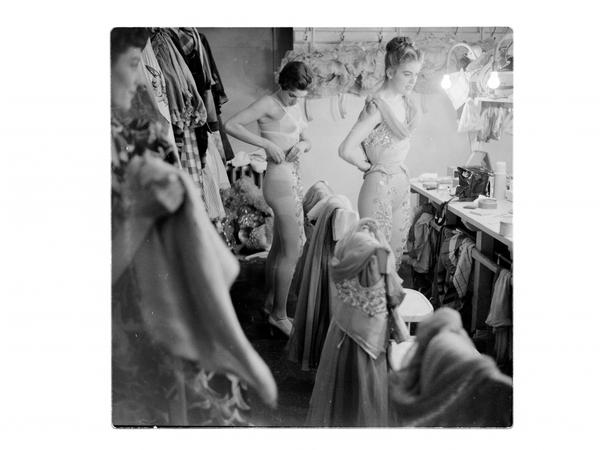

Drag performances were an important aspect of popular culture in the 1940s and 1950s. These behind-the-scenes photographs from a show in Islington are a testament to a form of entertainment that spans centuries.

Islington

1940s & 1950s

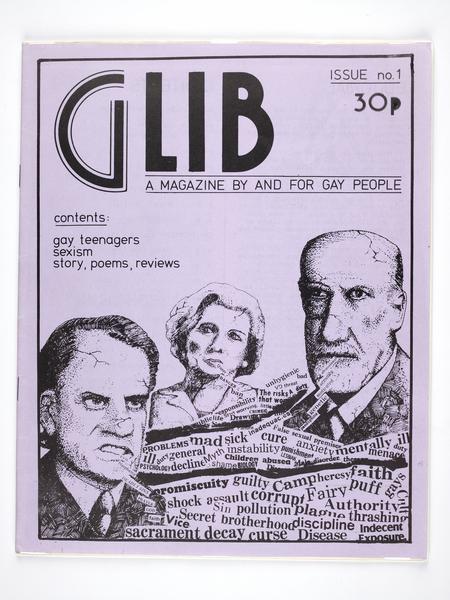

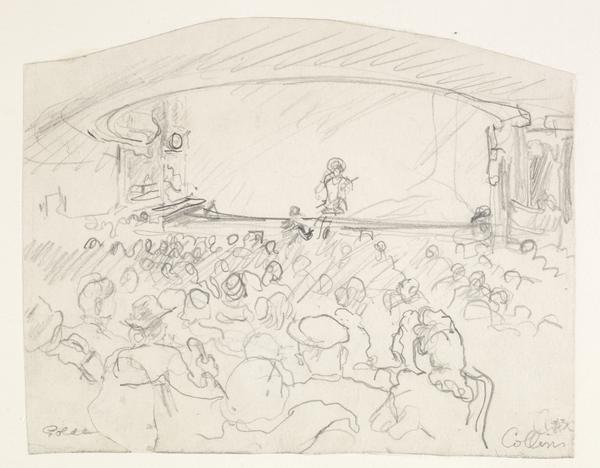

Backstage at Collins’ Music Hall, Islington, 1954.

The glamour and grit of post-war queens

Wigs, make-up, underwear, padding. Hats and hairspray, and cigarettes clenched between painted lips.

It’s May 1954 and we’re backstage at Collins’ Music Hall, Islington, as the cast of This Was The Army prepare for their evening drag performance. Photographer Alan Vines snaps away as the all-male performers transform themselves into glamourous women, entertain an audience, and head to the pub after the show.

Founded in 1946, This Was The Army was one of several drag revues in Britain after the Second World War. It was one of the longest running shows, touring for nine years. Vines’ photographs in our collection give us a rare insight into this world.

A history of drag in British culture

As Dr Jacob Bloomfield, an expert on drag history, points out, drag is not a phenomenon of the recent past. Cross-dressing performance goes way back – to Shakespearian times, for example, when male actors played female characters. It’s also been practised in many societies worldwide, including in ancient Greek theatre and Japanese Noh dance drama.

We know that the most common forms of contemporary drag (‘pantomime damery’ or glamour drag) have existed since at least the late 19th century. In fact, drag variety shows are an ingrained part of British popular culture. Some of Britain’s best-known stars of the post-war period were drag performers like Danny La Rue – whose stardom rivals that of RuPaul today.

Bobbie Barlow, posed and ready to perform.

Shows like This Was The Army, Soldiers in Skirts and We Were In The Forces were based on wartime army sketches in which servicemen played female roles to entertain the troops. Some of these sketches were turned into variety theatre after the war, and became a popular form of entertainment for audiences across the country.

So it’s surprising that we’re not familiar with more photographs of these shows. The negatives of these beautiful black-and-white pictures by Vines only resurfaced in the archives of a Kent-based photo agency. London Museum commissioned new gelatin silver prints from the original negatives, in a format likely to have been used by Vines himself. These are now held in our collection.

Alan Vines photographs This Was The Army drag revue

We don’t know much about Alan Vines or why he decided to photograph This Was The Army in 1954. But we do know he was working on a story for the Pictorial Press. We also know a few biographical details. He shared a darkroom with renowned photographer Grace Robertson, was described as having a chaotic lifestyle, and gave up his photography career in the 1960s.

The original lead story that was written to accompany the photographs – but was never published – comments on the success of their female impersonation. “Although the war days and the war boys are things of the distant past,” it says, “there is never any lack of recruits to the show in which, as the posters say, ‘Every Lady is a Perfect Gentleman’... And it is very remarkable indeed. The illusion of femininity is very strong, even when you get the other side of the footlights.”

Terry Dorset gets ready backstage.

The creation of this “illusion of femininity” required great skill and effort. Drag revues were hard work. Performers would usually do two shows an evening, six days a week, and they lived by travelling from place to place. All for a modest salary of £6–7 per week.

“It was a national phenomenon”

Who went to see drag revues?

We now often associate historic drag with transgression, especially in light of the moral standards of the 1950s. But the reality was much more complicated than that.

Drag revues were huge critical and commercial successes. People from all walks of life and classes across the country would come and see them. It was a national phenomenon and hundreds of thousands of people went to see the revues for a fun night out.

Audiences would have been both straight and queer, Dr Bloomfield points out, and there was little cultural consensus on the extent to which people explicitly associated drag with sexual immorality or homosexuality. The variety shows – with recurring acts like the mannequin parade, “dancing through the ages” and celebrity impersonations – were performed with great skill. This explains in large part why they were so popular.

Queer history and identity

Homosexuality and queerness were certainly part of the scene. For some people, this acknowledgement caused discomfort, while others overlooked it or saw it as part of the appeal.

‘Stage door Johnnies’ were a common sight, lingering outside the music halls after the shows, eager to join the chorus or to run off with one of the performers. At times, the police would attend the shows to make sure the performance was following the licensed scripts, and to keep an eye on what the performers and ‘stage door Johnnies’ did afterwards.

Men in Frocks is a 1984 book by Kris Kirk and Ed Heath that includes interviews with former post-war drag revue performers. It notes “for most of the queens, dragging was for fun, the camp and the giggle. But they began to realise that, even among their number, there were people who took it more seriously”.

Cross-dressing might have been acceptable on the mainstream stage, but it was much less so off-stage. Some of the performers would pluck their eyebrows and grow their hair out to make the daily ritual of wigs and make-up easier. But at a time when men’s fashions and appearances were much more prescribed, it didn’t take much to turn heads with a look that deviated even slightly from the norm.

The roaming lifestyles of drag performers

Drag as an expression of gender non-conformity was a motivation for some men to join the shows. Yes, the tone of the shows was comedic. But the impersonation of feminine glamour was an earnest effort. We can see this reflected in Alan Vines’s photographs. These are casual and intimate shots that reveal an authenticity to the performers’ body language, upheld even when fastening shoes, or coming down the backstage alley.

“it’s a hell of a life tramping from town to town… At least for a few hours every day we can be ourselves and enjoy it”

Paul Buckland, Chorus of Witches, 1959

Paul Buckland’s 1959 novel Chorus of Witches provides a fictionalised but insightful account of what it meant to be a member of the cast. One of the book’s main characters concedes: “It’s all right when you’re actually on the stage, knocking the audience cold with a bit of glitter and tit, but it’s a hell of a life tramping from town to town, spending every Sunday in a railway carriage and eating boiled cod in bed-sitting rooms practically every night of the week. And yet… we’d be far more miserable doing something else that we hated. At least for a few hours every day we can be ourselves and enjoy it.”

The images make us wonder: at a time when gender variance was little articulated, what would the inner lives and identities of these drag performers have been like? What did cross-dressing mean to them? And who might they have been today?

We’re grateful for the valuable insights provided by Dr Jacob Bloomfield, author of Drag: A British History, and Flora Smith and John Balean of Topfoto agency, who hold the rights to Alan Vines’s photographs. This story is partly based on a workshop with them.