The Battle of Cable Street

In October 1936, thousands of Londoners gathered to stop Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists marching through the East End.

Cable Street, Stepney

Sunday 4 October 1936

Fascism will not pass

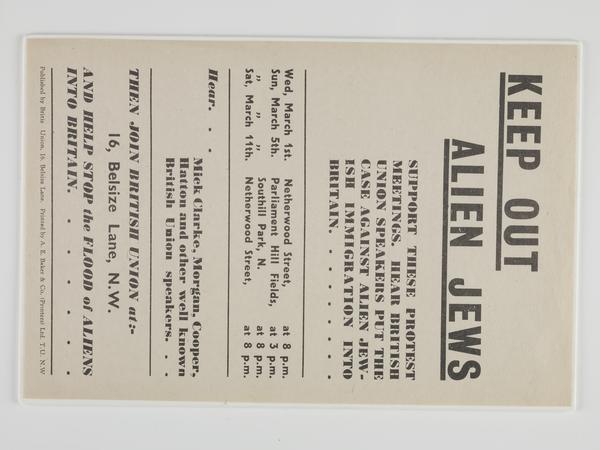

The fascists aimed to win support by dividing Londoners at a time of economic crisis, as have many other political groups past and present. Their march targeted the East End’s large Jewish community – who they used as a scapegoat for the area’s problems.

But the fascists never made it into Whitechapel. In what became known as the Battle of Cable Street, thousands of people, mainly local East Enders, came out and built barricades to stop them, clashing with police who tried to clear the way.

The event remains a symbol of Londoners’ resistance to the rise of fascism and antisemitism in the lead up to the Second World War (1939–1945).

Fascism in Europe

An international economic crisis in the 1920s turned many people in Europe towards more extreme political groups, led by strong, charismatic leaders. Communists and fascists called for drastic action, which appealed to people who’d lost faith in mainstream politics.

The far-right fascists wanted to restrict immigration and blamed immigrants for economic hardship.

Fascism in Britain

The British Union of Fascists (BUF) was founded in 1932 by Oswald Mosley, who had previously been an MP for the Conservatives and Labour. The BUF took inspiration and funding from the fascist movement in Italy, headed by Benito Mussolini, and the Nazi party in Germany, headed by Adolf Hitler.

They styled themselves like a military organisation, becoming known as “blackshirts” for their menacing uniform.

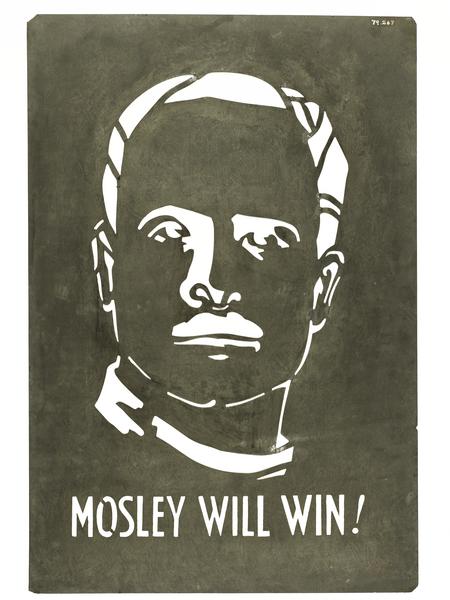

Thousands of people attended events organised by the BUF in 1933. The Daily Mail newspaper wrote in support of the party. In our collection there’s a stencil of Mosley’s face, possibly used to make campaign posters for the BUF or to paint Mosley’s face onto walls around the East End.

In 1934 the BUF gained a reputation for violence when their supporters attacked protestors disrupting a meeting at the Olympia Hall in Kensington. The Daily Mail’s publisher dropped its support as a result.

A stencil of Mosley's face, used to make posters or paint walls.

Why did the fascists want to march in the East End?

Mosley’s fascists followed the Nazi’s example of falsely blaming Jewish “immigrants” for society’s problems.

London’s East End was home to the city’s largest Jewish community. The area’s different communities largely lived together peacefully. But antisemitic views did exist, often driven by fears about competition for housing and jobs.

The BUF aimed to win support there by promoting antisemitism. In 1936, the party planned a march into the heart of the East End. Tens of thousands of people signed a petition to the Home Secretary to ban the march, but he refused.

What happened on Cable Street?

On Sunday 4 October 1936, 3,000 fascists gathered close to the Tower of London, with 7,000 police as protection.

The fascists intended to march into Whitechapel. But a huge crowd of East Enders and anti-fascists had gathered to stop them, possibly as many as 50,000.

Jews ignored the warning of the Jewish Chronicle newspaper to “keep away from the route of the Blackshirt march”. Instead they stood alongside dock workers with Irish heritage, Somali seamen, communists, and trade union and Labour party members.

“they were pelted with missiles and forced back”

Barriers were built from mattresses, corrugated iron and furniture on Cable Street and further north, at the junction of Leman Street and Commercial Road. A tram driver is said to have abandoned his tram in the middle of the road to help block the march.

The police attempted to clear the barriers, and charged the protestors blocking the route on horseback. But they were pelted with missiles and forced back.

Around 80 anti-fascists were arrested. At least 73 police officers were injured and dozens of men, women and children were hurt. 15 were sent to hospital.

The fascists were forced to abandon their original plan, with the police telling them to head back to central London. They eventually reassembled at Hyde Park.

The police make arrests in the wake of the Battle of Cable Street.

What happened afterwards?

East Enders partied in the streets.

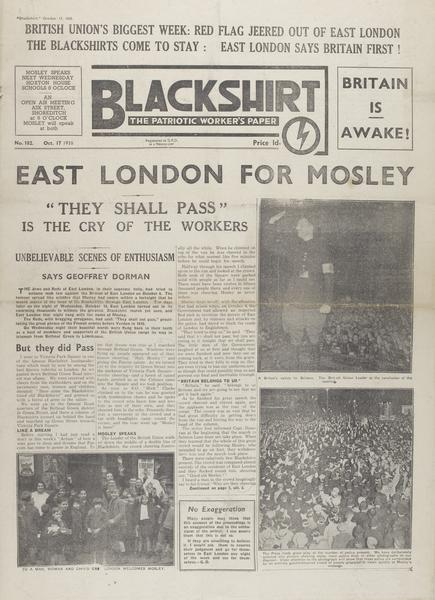

The Battle of Cable Street was rightfully celebrated as a victory against fascism. It showed that united community resistance could defeat right-wing extremism. Inevitably, the BUF saw things differently, as seen in this issue of the BUF’s newspaper from our collection. In the 1970s, a large mural was painted on Cable Street in Shadwell to commemorate the event.

The Battle of Cable Street was a turning point. The 1936 Public Order Act which was rushed through Parliament required march organisers to seek permission from the police. A ban was also placed on demonstrators marching in uniforms.

In 1939, Britain entered the Second World War against the fascist powers of Germany and Italy. Mosley and other members of the BUF were held in prison to stop them from helping the enemy. Mosley and his wife, Diana, spent most of the war together in a house in the grounds of Holloway Prison.

Police clashed with protestors in 1962 in Trafalgar Square, where Mosley was set to speak.

Two decades later, in 1959, Mosley unsuccessfully ran to become the MP for North Kensington. His anti-immigration campaigning there was extremely provocative, coming soon after a local outbreak of racial tensions, when white gangs had roamed through Notting Hill attacking its Black community.

Mosley’s later political activity drew more protest – our collection includes photos of an anti-Mosley crowd protesting a rally at Trafalgar Square in the 1960s.

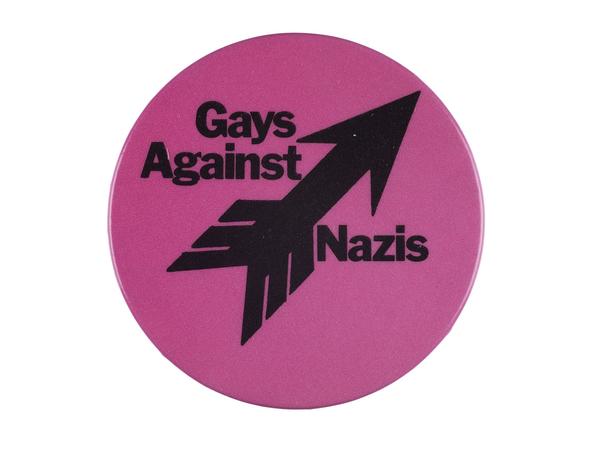

The events at Cable Street showed how a local community could come together to confront extremism and influence political change. Its legacy continues to inspire people to stand up against fascism and racism.