Albertopolis: Prince Albert’s London legacy

Albert, prince consort of Queen Victoria, was a champion of art, design and technology. His vision helped reshape London’s cultural landscape in the 19th century.

South Kensington

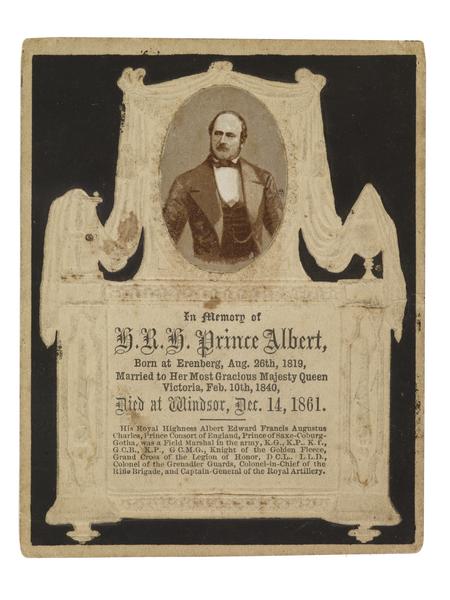

1819–1861

Pursuing the intellectual and the aesthetic

Why are there so many concert halls, universities and museums packed in together in South Kensington? Well, it’s largely thanks to Prince Albert, husband of Queen Victoria and an enthusiastic supporter of culture, science, education and industry.

During his 21 years of marriage, Albert dedicated much of his time to championing new technological developments. This culminated in his biggest project, the hugely successful and profitable Great Exhibition of 1851 in Hyde Park.

Albert wanted to transform the area around the Exhibition into a hub for science and arts in London. He died before he saw his vision realised. But this so-called ‘Albertopolis’ can still be seen as his legacy.

“Albert… is extremely handsome”

Queen Victoria, 1836

Marriage to Queen Victoria

German-born Prince Franz August Karl Albert Emanuel first met his cousin, the soon-to-be queen Alexandrina Victoria, on her 17th birthday in 1836. By all accounts, it was love at first sight. “Albert… is extremely handsome,” Victoria wrote in her diary, “his eyes are large & blue, & he has a beautiful nose, & a very sweet mouth with fine teeth.”

Victoria and Albert married at the Chapel Royal in St James’s Palace in 1836. They were a popular couple, and they gave birth to nine children between 1840 and 1857.

Over the course of their marriage, Albert also began to take on more of the queen’s royal responsibilities. By 1857, he was awarded the title prince consort, recognising his work supporting his wife in her duties as sovereign.

Champions of art, science and technology

Albert took an active interest in the arts as well as new developments in science and technology. He and Victoria fitted out their royal homes with the latest in Victorian tech, including hot water central heating, light bulbs and electric telegraphs. Albert was also a skilled painter, organist and singer. He held various roles in arts and literature organisations.

These interests combined in one of his great passions: photography. He and Victoria began commissioning and collecting photographs in the 1840s, when photography as a medium was just getting started. They continued to support and promote photography as it became more commercially successful. Both were appointed patrons of the Photographic Society of London in 1853.

The Great Exhibition of 1851

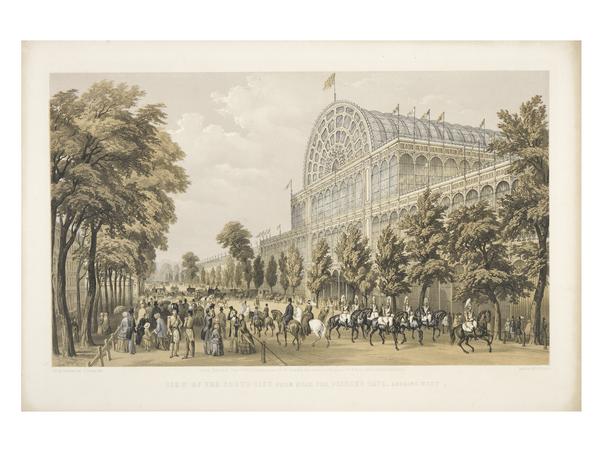

Albert’s largest project was the Great Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations, which he devised with civil servant Henry Cole. The Exhibition showcased modern design, industry and art while promoting a positive view of the British empire to the masses. It took place in the purpose-built Crystal Palace in Hyde Park between 1 May and 15 October 1851.

“I am more dead than alive of overwork”

Prince Albert, 1851

Albert played a key role in planning and supervising the Great Exhibition. He established a Royal Commission and, as its president, organised 13,937 exhibitors from over 30 countries to bring more than 100,000 products to London. Quite a logistical challenge. “I am more dead than alive of overwork,” Albert admitted in a letter to his grandmother weeks before the grand opening.

But the Exhibition was viewed as a spectacular success. It was the first international exhibition of its kind. Over six million people walked through its doors. And it turned over a very healthy profit of £186,437 – around £20 million in today’s money.

Albertopolis in South Kensington

Albert was adamant that the Exhibition “should not become a transitory event of mere temporary interest,” as he wrote in 1851. So the Royal Commission for the Exhibition of 1851, of which Albert was the chair, bought a site in nearby South Kensington. It was developed into a new centre for culture, education and science.

In the 1850s and 60s, the area became known as Albertopolis. And the road running through it was renamed Exhibition Road.

The South Kensington Museum transferred to Exhibition Road in 1857. But after suffering from bouts of ill health – exacerbated by the stress of putting on the exhibition – Albert died shortly after in 1861.

In the years following Albert’s death, the South Kensington Museum became the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Science Museum. The Royal Albert Hall (1871), also named in his honour, and the Natural History Museum (1881) opened their doors. As did the sites of the Royal Geographical Society and the Imperial College of Science and Technology.

The Albert Memorial in nearby Kensington Gardens opened in 1872. The statue of him seated, looking south towards Albertopolis, still stands there today.