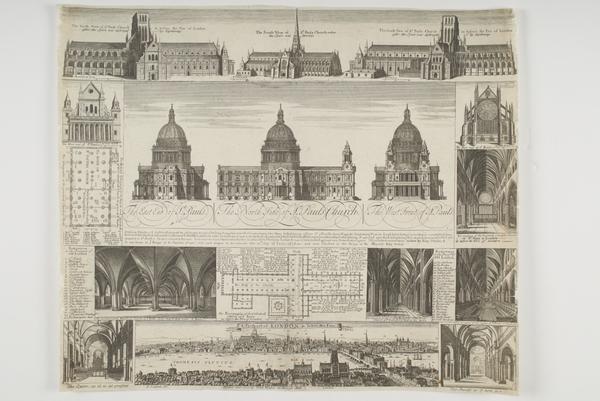

A history of St Paul’s Cathedral

A historic church rebuilt after the Great Fire of London 1666, the story of St Paul’s takes in national ceremonies, bomb threats and the vision of acclaimed architect Christopher Wren.

City of London

1711

London’s symbol of survival

St Paul’s Cathedral sits on top of Ludgate Hill, at the highest point in the City of London. It’s the same site as the important medieval cathedral, now known as Old St Paul’s, which was destroyed as the Great Fire of London swept through the city in 1666.

The present building was designed by architect Christopher Wren. You can probably picture it in your mind's eye: white Portland limestone, a Greco-Roman-style facade and, of course, an iconic, towering dome. Few buildings have been so strongly associated with the image of London quite like this one.

What was Old St Paul’s Cathedral?

Old St Paul’s was London’s fourth cathedral dedicated to Saint Paul the Apostle, one of the early Christian leaders. The first cathedral was established in 604 CE – possibly on the same plot atop Ludgate Hill. These cathedrals were the focal points of medieval London’s religious, political and social life.

Construction started on Old St Paul’s Cathedral in 1087, after the previous three cathedrals were destroyed by fire or Vikings. It was eventually completed in 1314. The building was huge. It featured Europe’s highest spire at the time – which stood even taller than the current dome does, before it burned down in 1561.

By the early 1600s, the cathedral had fallen into disrepair. Renovation works that had begun in the 1630s were halted by the English Civil Wars (1642–1651). And then in 1666, it was completely gutted by the Great Fire of London.

Who built St Paul’s Cathedral?

The present-day cathedral was designed and built under the supervision of architect Christopher Wren, who’d already been involved in advising on the repair of Old St Paul’s before the Great Fire.

The final design for the building took nine years to develop. It combines different architectural styles, with slender towers typical of theatrical Baroque churches, and a grand colonnaded entrance influenced by ancient Greek temples.

Wren also took on the architectural challenge of building a dome, rather than a steeple, on the cathedral. He had to call on the help and expertise of his scientific friends in the Royal Society, including Isaac Newton, who’d recently decoded the laws of gravity. The final dome was made from an outer dome, an inner dome and a supporting brick cone concealed between the two. It’s one of the largest domes in the world.

How tall is St Paul’s cathedral?

The cathedral is 111 metres high – and for over 250 years, it was the tallest building in London. Its skyscraper crown was stolen in 1963 by the 118-metre-tall Vickers Tower (now known as Millbank Tower) in the City of Westminster. But it’s now completely dwarfed by The Shard, which stands 309.6 metres high.

“Without, within, below, above, the Eye / Is fill’d with equal Wonder and Delight”

James Wright, 1967

How long did it take to build St Paul’s?

It took 35 years to build St Paul’s – actually a relatively short time to build a cathedral of that size.

The first service was held there years earlier in 1697, when the west end and dome were still to be built. Writer James Wright recorded his impressions of the cathedral that year in a poem. “Without, within, below, above, the Eye / Is fill’d with equal Wonder and Delight,” he wrote, “... such a City fits a Church like Pauls”.

Construction finished in 1710 when Wren’s son (also called Christopher) put the final stone in place. On Christmas Day 1711, Parliament declared the new St Paul’s Cathedral officially complete.

Who’s buried in the crypt of the cathedral?

Fittingly, Wren was laid to rest in St Paul’s crypt in 1723. On a nearby wall, an inscription reads, in Latin, “Reader, if you seek a monument, look about you”.

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, and Horatio Nelson – two British military leaders who became heroes during the Napoleonic Wars (1793–1815) – were both buried there.

Celebrated painters like Joshua Reynolds and JMW Turner were buried at St Paul’s. As was caricaturist and illustrator George Cruikshank, whose remains were moved from Kensal Green Cemetery to the cathedral in 1878. Many of Cruikshank’s prints are in our collection.

Funeral card from the funeral of Joshua Reynolds.

What events have taken place at St Paul’s?

As an iconic London landmark, the cathedral has hosted a number of prestigious ceremonies and spectacles over the years.

Many of these have been happy occasions. Jubilee celebrations for Queen Victoria, King George V and Queen Elizabeth II have featured events at St Paul’s. And Prince Charles and Diana Spencer chose to get married there in 1981 over the traditional Westminster Abbey. The cathedral could fit their large guestlist – and accommodate the hundreds of thousands of people watching along the procession route.

St Paul’s has also been a site of mourning. It hosted large funeral services for Nelson, Wellington and prime ministers Winston Churchill, who died in 1965, and Margaret Thatcher, who died in 2013. In 2017, more than 1,500 people attended a National Memorial Service there for the 72 people killed in the Grenfell Tower fire.

On 15 October 2011, Occupy London activists set up a camp outside the church to protest social and economic inequality. They remained there until they were evicted by the Corporation of London on 28 February 2012.

Why is St Paul’s Cathedral important?

St Paul’s is one of London’s most widely recognised landmarks. It’s a place of particular architectural and historical significance. The backdrop to many of London’s major events. A sanctuary of Christianity. A major tourist attraction. And an inspiration for artists, as seen in the many depictions of St Paul’s in our collection.

But St Paul’s has also been transformed into a symbol of London’s resilience. Reborn after the Great Fire, the cathedral escaped major damage when the German air force bombed the city during the First and Second World War. Photographed among London’s smoky skyline in 1940, it provided the powerful image to match the city’s ‘Blitz spirit’.

In 1913, it even survived a bomb plot by the Suffragettes during their militant campaign for women’s right to vote. Militants planted an explosive device made from an empty mustard tin and parts of a watch in the cathedral choir – but a bell-ringer discovered it before it exploded.