The 1918 election: When women first voted

In 1918, after decades of campaigning, some women finally won the right to vote in a British general election. About 8.5 million women were allowed to vote and 17 women stood for Parliament.

14 December 1918

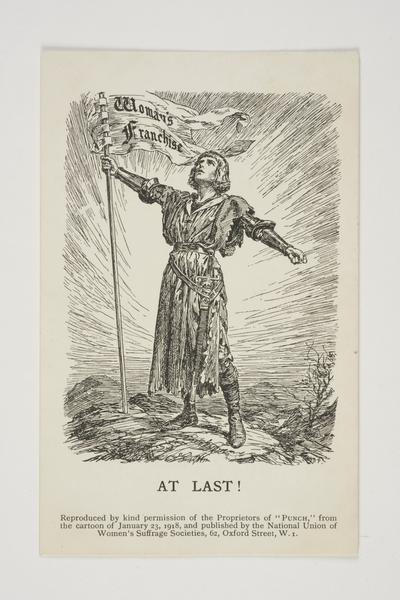

Campaigning in Smethwick on behalf of Christabel Pankhurst.

A vote for change

The December 1918 election was held just a month after the fighting of the First World War had ended. It also came four years after the Suffragettes had halted their militant campaign to win votes for women.

Both were significant in shaping the 1918 Representation of the People Act, which set new rules on who could vote. For the first time, votes were given to all men over 21 – and some women over 30.

It wasn’t a total victory for women’s voting rights. It wasn’t equality. But it was a major step forward.

On 14 December 1918, with the tragedies of the First World War lingering in their minds, women walked shoulder to shoulder with their husbands, brothers, sons and lovers to vote for the first time in a general election.

“At the previous general election in 1910, no women were allowed to vote”

Who could vote before 1918?

At the previous general election in 1910, no women were allowed to vote.

Only 58% of men over the age of 21 could vote. Men needed to own or rent property above a certain value to qualify, leaving millions without a vote.

Strangely, some male voters could vote twice: once in their home district, then once in their university constituency, or where they owned property.

How did women get the right to vote?

Women had campaigned for the right to vote since the 19th century. Then, between 1906 and 1914, a group of women known as Suffragettes used more extreme, militant protests to demand change.

When the First World War began in 1914, Suffragettes and non-militant suffragists stopped their active campaign to support the government’s war effort instead. Once enemies, the Suffragettes and the government were now united behind a common cause.

Millions died on European battlefields in the next four years. Women in Britain took new jobs in factories and farms to help Britain achieve victory. This changed views about women’s place in society and their economic value.

At the same time, the government realised that electoral changes were needed to reward the many thousands of returning British soldiers who couldn’t vote under the existing system.

Pre-1918 rules said men had to have lived in Britain in the past year to vote – but many soldiers had been stationed abroad. And many working-class soldiers were excluded by restrictions requiring them to own or rent property of a certain value.

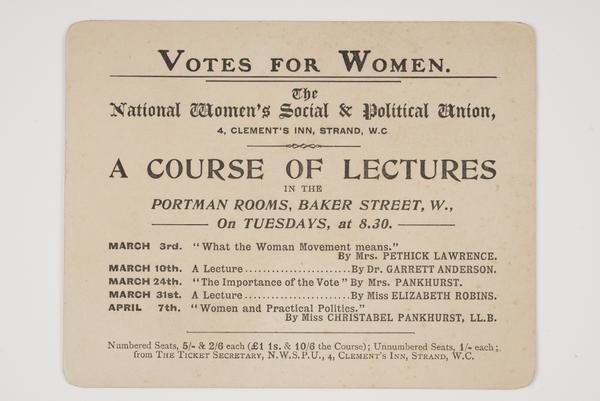

A pro-female suffrage postcard commemorating the passing of the Representation of the People Act.

The 1918 Representation of the People Act

This act, sometimes called the Fourth Reform Act, gave the vote to all men over 21. It also brought in postal and proxy votes for those away from home.

More significantly, the new rules meant that for the first time 8.5 million women – 40% of Britain's female population – could vote at the 1918 general election.

But the rules still discriminated against women, leaving millions without a vote.

“Many of the 1,300 women who went to prison battling for the right to vote were still too young to vote in 1918”

Which women could vote?

The 1918 Representation of the People Act gave the vote to women, so long as they were over the age of 30 and were either:

- a property owner

- a graduate voting in a university constituency

- a member or married to a member of the local government register (which lists who can vote in local elections)

Many of the 1,300 women who went to prison battling for the right to vote were still too young to vote in 1918.

Vera Wentworth, who had campaigned for votes for women for a decade, was 28, and therefore still too young, at the time of the election.

The age limit maintained a male majority

Due to the tragic deaths of a generation of young men in the First World War, there were over a million more women than men in Britain. If women had been given equal voting rights to men, they would have outnumbered male voters.

The 1918 Act prevented that from happening. Instead women made up only 40% of the electorate, the people who could vote.

In 1918, government minister Lord Cecil admitted in Parliament that the age limit was introduced to prevent women from being the political majority: “That is the reason why the age limit of 30 was introduced… for fear they [women] might be in a majority in the electorate of this country."

Suffrage campaigners like Milicent Fawcett were disappointed at the continued discrimination, but accepted it as a necessary and temporary compromise to get the vote.

The deaths of men in the First World War meant that there were over a million more women than men in Britain.

Nobody knew how women would vote

There was great interest around if and how women would vote, and how politically informed they were.

The day after the election, the Sunday Pictorial newspaper made reference to “Mrs Granny Lambert of Edmonton, who is on the voters’ register for the first time. She is 105 years of age, and says she has never heard of Mr Lloyd George”. David Lloyd George was the Liberal prime minister re-elected in 1918.

Women’s supposed ignorance about politics was a common theme in anti-suffrage propaganda. Even supporters were worried about helping new electors. This card urging voters in Smethwick to choose Christabel Pankhurst as their Member of Parliament (MP) shows how to fill out a polling card.

A card showing how to vote.

Emily Phipp, who ran as an independent candidate in Chelsea, set up a model polling booth where women could practise voting. She also made arrangements to care for mothers' babies while they went to the polls.

Women could stand to become MPs for the first time

A total of 17 women ran as candidates in 1918, from political parties including Liberal, Conservative, Labour and the Women's Party.

Senior figures in the Suffragette campaign, who’d been empowered by their experiences, stood as MPs. These included Christabel Pankhurst and Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence from the Women's Social and Political Union, and Emily Phipps of the Women's Freedom League.

“In 1928, women were finally given the right to vote on equal terms with men”

One woman was elected in 1918

Of the 17 female candidates, only Constance Markievicz was elected to Parliament.

Markievicz stood for the Sinn Féin party in the constituency of Dublin St. Patrick's, in what was then British Ireland. Sinn Féin supported Irish Independence – so its elected MPs refused to go to Westminster to serve in the House of Commons.

It wasn’t until 1919 that Nancy Astor became the first woman MP to serve in the House of Commons.

Countess Markievicz wearing the uniform of the Irish Citizen Army.

The struggle for equality continued

Ten years later, in 1928, women were finally given the right to vote on equal terms with men by the Equal Franchise Act.

But votes for women was only the starting point for the Suffragettes. They believed that having women in Parliament would lead to laws that could improve the lives of all women and make progress towards equality.

After their narrow defeats in the 1918 election, many of the former Suffragettes continued their political struggle. Some moved abroad, to countries such as the United States or Australia, to campaign there for suffrage and other social causes affecting women.

Contains edited content originally written by Alwyn Collinson, Digital Editor.