25 October 2023 — By Francis Marshall

Youth: A rare Festival of Britain sculpture by Daphne Henrion

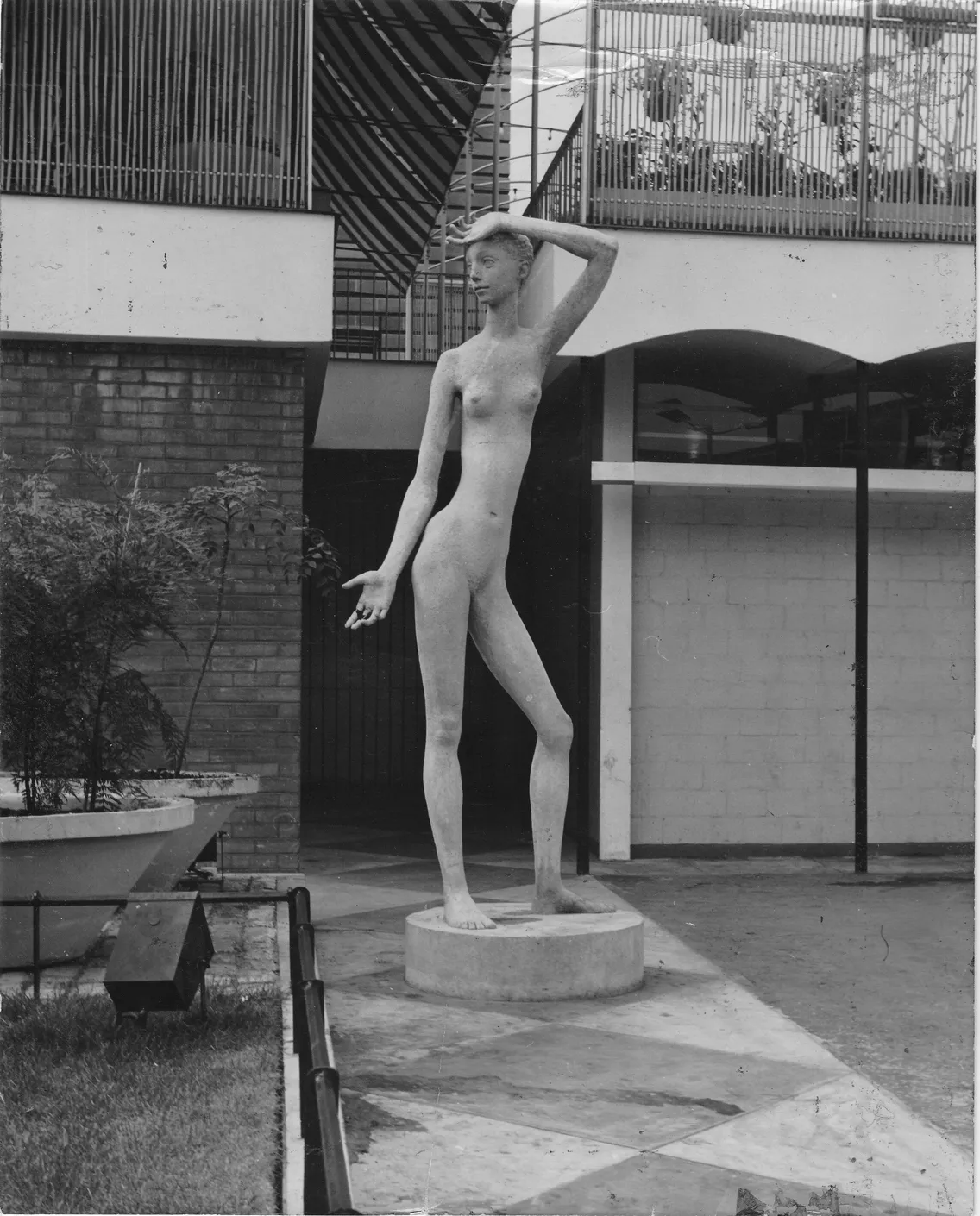

A striking, figurative sculpture by artist Daphne Hardy Henrion, ‘Youth’, has survived from the 1951 Festival of Britain. Lost to the public for around 70 years, the sculpture has been restored and is now part of our collection.

The 1951 Festival of Britain celebrated the nation through science, technology and industrial design. So it shouldn’t have been a surprise to conservators when the museum acquired a sculpture by Daphne Hardy Henrion to find that it was made in an experimental material that has yet-to-be fully identified. The cast, lost to the public for decades, is an alternative to one that was famously exhibited at South Bank during the festival.

But how did this rare survival from the Festival of Britain come into the museum’s collection, and where was it all this while?

“The 9ft-tall striking female figure 'Youth' had been standing in the garden of a house in Pond Street, north London, for 70 years”

The 9ft-tall striking female figure named Youth had been standing in the garden of a house in Pond Street, north London, for 70 years. But London’s weather, wind, rain, hot summers, cold winters and pollution had taken its toll. Once a pristine white, Youth was now stained a dark grey-green. More significantly, one of its arms was shattered, a hand was badly damaged, and there were numerous cracks and losses across the surface.

Youth was made for the 1951 festival, where it was displayed outside the ’51 bar and restaurant, on the South Bank. It was commissioned by architect Leonard Manasseh, designer of the ’51 bar and adjacent grounds. A showcase for the best modern British art, design and architecture, the festival provided commissions for many leading artists and makers, including Daphne Hardy Henrion.

Who was Daphne Hardy Henrion?

The young artist had trained at the Royal Academy Schools in London from 1934 to 1937. Afterwards, she established herself as a figurative sculptor at a time when abstraction was prevalent. Influenced by Greek, Roman and Italian Renaissance sculpture, she was noted for her sensitive portraits, particularly of children. For a time she lived with the Hungarian writer Arthur Koestler, whose novel Darkness at Noon, she translated into English from the original German. Later she married the influential German designer Henri Kay Henrion. Her portraits include Koestler, Cider with Rosie author Laurie Lee, as well as her husband’s. Her public works included a 1946 memorial to the victims of Belsen.

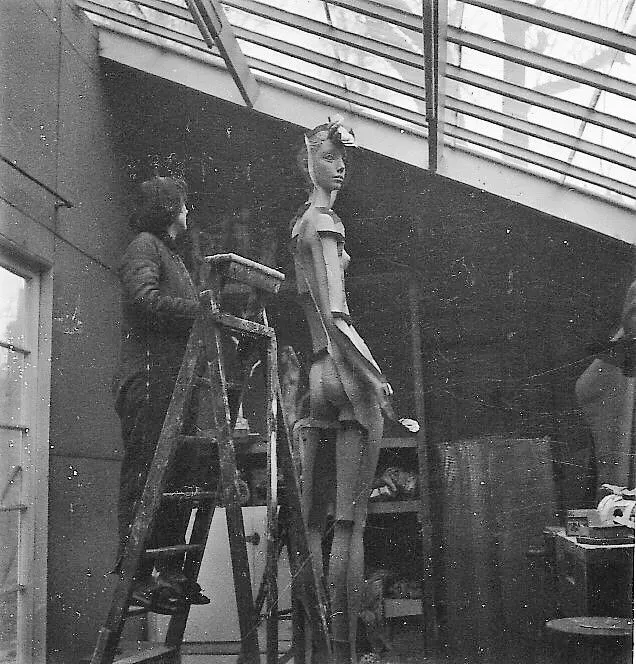

The artist at work on the clay original of Youth in her Hampstead studio. The fin-like structures will be used to create the section moulds for the casting process.

Youth-ful experiment, and the 1951 Festival of Britain

In 1951, Henrion made two casts of Youth. Cast, as opposed to carved, sculpture is produced from moulds and multiple versions of the same image can be made. Usually, the casts are limited to a small number. In the case of Youth, both casts derive from a now lost clay original, from which section moulds would have been created. Section casts would have made from the moulds and then joined together to create the whole figure. Photographs of Henrion at work on the sculpture in her Pond Street studio show exactly this process.

The cast, finally installed at the Festival of Britain, was made of concrete. There was even an article in the glamorously named magazine Concrete Quarterly (Autumn 1951) discussing Youth along with other concrete sculptures at the festival. Yet, when the museum’s cast was properly inspected by us and the conservators at Taylor Pearce, it clearly was not made of concrete, or anything like it! If anything, it looked like a form of fibreglass resin coated with a layer of paint or lime wash.

Fragments sent for analysis suggested a ceramic component to the medium, but without firmly identifying the material. Sculptors at this period often experimented with new materials – concrete is an obvious example – and clearly Henrion was no exception.

Following the demolition of the festival site, the Southbank cast was eventually moved to the garden of Leonard Manasseh’s home, also in Hampstead, where it currently still stands. Conservators at Taylor Pearce had recently worked on this cast, too, and confirmed it was, indeed, concrete. Which means the museum’s cast is an alternative version, made in an experimental material – and needs further analysis.

Bringing Youth to London Museum, and what’s next?

To ensure its long-term preservation, the artist’s family has given the sculpture to the museum. So, on a fine day in December 2019, if you were crossing Henrion’s family home in Hampstead, you would have seen the conservators at Taylor Pearce carefully removing it from its setting. To keep it stable and avoid further damage, the figure’s legs had been wrapped in cling-film, encased in plaster and buttressed with struts. Once extracted, it was taken to their south London studio where, over many months, throughout the Covid-19 lockdown, it was restored.

Interestingly, we don’t know why Henrion made two versions of such a large sculpture. To produce just one was a significant commitment of time, effort and materials. Whatever the reason for the two versions, the sculpture was obviously important to her. She kept it and put it on display in her own front garden, after all. Family photographs show the artist’s son, Paul, then aged about three, sitting at the feet of the statue.

Today, Youth is fully conserved and currently housed in the museum’s large object store awaiting exhibition. But not quite fully restored. Once conservators had cleaned and mended the figure, we had to decide whether to repaint it white or retain the colouration which had developed after so many years exposed to the elements. In the end, after much discussion, we felt that it was important to retain something of the sculpture’s history. We decided not to repaint it. The light grey patina Youth now displays resembles the weathered appearance common to many outdoor sculptures. We won’t, though, be displaying it outside in future.

Youth is a rare survival from a time of cultural optimism. Much of the art and design made for the Festival of Britain was scattered and lost once it was over. The concrete version displayed on the South Bank did survive but is in private ownership. We are therefore fortunate to have this alternative cast, owned by the artist herself, now fully conserved, as part of the London Collection.

Francis Marshall is Senior Curator (Paintings, Prints and Drawings) at London Museum.