02 December 2022 — By Beverley Cook, Guy Atkins

‘We Are What We Eat’: An exploration of food in prison

Brought together by members of the Prison Art Group at HMP Pentonville for London Museum’s collecting programme, London Eats (Curating London), the artworks here present an honest account of prison food and call for change.

“They say a picture speaks a thousand words. If only my taste buds could paint a picture. Being a big foodie has made food an issue for me at HMP Pentonville. Before I even arrived here, for the second time, I was dreading how much weight I would lose.” Ahmed M., member, Prison Art Group

At the end of 2021, London Museum approached HMP Pentonville to ask if people serving sentences would be interested in contributing to ‘London Eats’, a year-long community project that aimed to document, record and collect around the subject of Londoners’ relationship with food. The museum aims to reach all Londoners through its contemporary collecting programmes. Approaching HMP Pentonville to take part in ‘London Eats’ provided the opportunity of reaching out to a prison community and taking seriously the experience of Londoners living within this very challenging environment.

The HMP Pentonville Prison Art Group agreed to participate in the project on one condition: that through its art, it could give an honest and unfiltered account of prison food.

Over six months, the group produced over 40 artworks and short texts on the subject of prison food, which they self-published in the booklet We Are What We Eat, available in print and online. The project flourished through the commitment of members of the Prison Art Group, especially Ahmed G. who took on the project lead role. At the same time, the project benefited from the support of prison management, our commissioned artist-researcher, prison educators led by José Aguiar, and designer Patrick Fry.

“I think food plays a part in rehabilitation”

Ahmed M

The group nature of the project was a rare chance for people in Pentonville to come together and discuss as a team how their experiences should be represented and displayed. This is demonstrated by how much the artworks speak to each other, and how a quote by one person echoes the artwork of another. The Art Group were fully involved in the production of the booklet, assisting with editing and advising on the selection and layout of artworks and quotes.

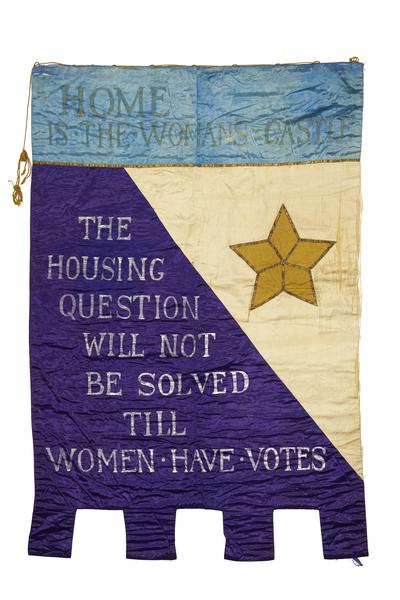

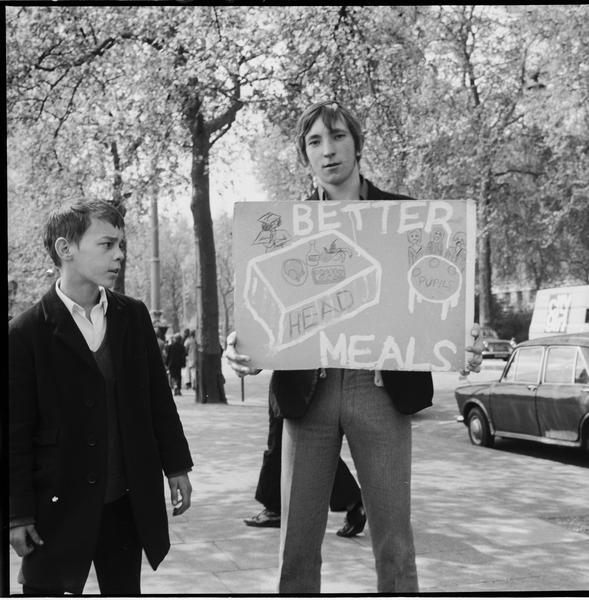

With references to artists such as Barbara Walker, MF Husain and Diego Velázquez, the finished booklet is an extraordinary document. It demonstrates the talent, ingenuity and perseverance of the men who took part, as well as the care and dedication of the prison educators who support them. In creating the booklet, the men drew from historical pamphlets in the museum’s collection – such as those disseminated by the Suffragettes – as well as the political pamphlets collected by George Orwell. As a result, the booklet makes a powerful case for prison food to be improved. For the participants it was important the booklet was perceived not as a health guide for people in prison but rather a call for change.

“Food is an essential part of a person’s day. What we eat determines how our day goes and how we feel. I know I feel much better after I have had a good meal, so I think food plays a part in rehabilitation,” says Ahmed M.

‘The kettle is a holy object’

The cell kettles feature in a number of the artworks. Used to cook food purchased by the canteen – such as pasta, tuna and hot chilli sauce – they provide a vital, additional source of nutrition. “You can make good food in your cell, with what you buy from the canteen list. Tin of chickpeas 59P, tin of Tuna £1.30...,” says Tommy. Ahmed M. further explains, “A kettle in a prison has more purposes than anywhere else. A saviour for the inmate who craves for a dish made with love, a taste of the outside, a creation of your own. It is a precious object for all prisoners who cook in them and get fed from them. The hob of the kettle sees so many unexpected items that it welcomes, from being a rice cooker to a frying pan. It gives you more life than expected.”

The cell kettles feature in a number of the artworks. Used to cook food purchased by the canteen – such as pasta, tuna and hot chilli sauce – they provide a vital, additional source of nutrition. “You can make good food in your cell, with what you buy from the canteen list. Tin of chickpeas 59P, tin of Tuna £1.30...,” says Tommy. Ahmed M. further explains, “A kettle in a prison has more purposes than anywhere else. A saviour for the inmate who craves for a dish made with love, a taste of the outside, a creation of your own. It is a precious object for all prisoners who cook in them and get fed from them. The hob of the kettle sees so many unexpected items that it welcomes, from being a rice cooker to a frying pan. It gives you more life than expected.”

Food is currency, it’s home…

Understandably, food has a broader significance within the prison community. There are times when “Food is a currency. Any spare food is traded. I trade food for haircuts,” explains Bouakai. Human depicts the feeling of home in ‘Smell Is Free’. “The smells of people cooking in their cells makes me jealous. When I smell fish I think of home,” he shares.

On the other hand, Ahmed G. writes, “Cooking in your cell is pressured. You only have one shot as you have no more food. You rewire your kettle so it doesn’t cut out, so it keeps on cooking your food. The kettle is a symbol of us rejecting the food of the prison.”

The reality of menus

Many of the artworks identify a clear link between inadequate food and the men’s well-being and morale. In his artwork ‘Fend for Yourself’, Ahmed M. brings attention to the long gaps between meals. The works also highlight the struggles of those who do not have access to money to buy food for cooking and eating in their cells.

The art group’s responses to prison food are also represented in the booklet. Osman writes, “Menus give a great deal of misconception. Everything on the menu sounds great. The reality is, it’s not.” While Ahmad says, “Everything is the same here…the menus repeat every two weeks. Then once a month you get a beefburger. No bun just the patty.” “They give you just a taster of the outside world. A spoonful,” recounts Miah.

Damien’s artwork, ‘We Are What We Eat’, shows the daily ritual of collecting the food from his wing’s servery. “There’s no shared area to eat. When you get back to your cell your legs are sore and your food is cold,” Damien explains.

“The kettle is a symbol of us rejecting the food of the prison”

Ahmed G

Creativity in adversity

The artworks highlight the resourcefulness and resilience of those serving sentences at HMP Pentonville. The Prison Art Group felt it important to demonstrate how — for those with enough money to purchase items to cook in their cells — food offers a chance for self-expression and community. There are times when “Someone takes the role of Chef. They cook for guys around them,” writes Ahmed G.

Creative expression within the prison environment brings many challenges. The participating members of the Prison Art Group showed a determination to confront and overcome issues that threatened the project including extended confinement due to the Covid-19 lockdown: for six weeks of the project, the men were confined to their shared cells for more than 23 hours a day.

This commitment ensured the project outcomes exceeded all expectations. The museum was incredibly proud that several of the artworks received commendations at the Koestler Awards for arts in criminal justice. Five of these — by Tommy, Paul, Ahmed M., Dean and Damien — were selected for display at the 2022 Koestler Arts exhibition in London, curated by the artist Ai Wei Wei.

“In this booklet, a few individuals have come together to express our opinions on the food at Pentonville in a creative way. We hope you can appreciate the work we have put together," shares Ahmed M.

Download

PDF: 5.3 MB

‘We Are What We Eat’ formed part of London Eats (Curating London), a London Museum programme supported using public funding by Arts Council England.

During the project, the Pentonville Prison Art Group consisted of Ahmed G. (project lead), M.I.A., Damien, Ahmed M., Paul, Miah, Ahmad, JK, Francisco, Human, Tommy, Robert, Frank, Elvin, Alexander, Dean, and Bouakai. In May 2022, the group presented copies of the booklet to both London Museum and the prison's management at a launch in the prison library.

The group was supported by artist-researcher Guy Atkins, prison educators Kirk Lawrence, Jose Aguiar and Helena Baptista, graphic designer Patrick Fry, and London Museum curator Beverley Cook.