17 December 2024 — By Mariarosa Spanu

Holiday broadsides: When tip requests were sheer poetry

In 1700s–1800s London, service workers created beautiful broadsides with verses and artwork, asking residents for holiday tips. Today, this artistic approach to seasonal gratuities is a lost art.

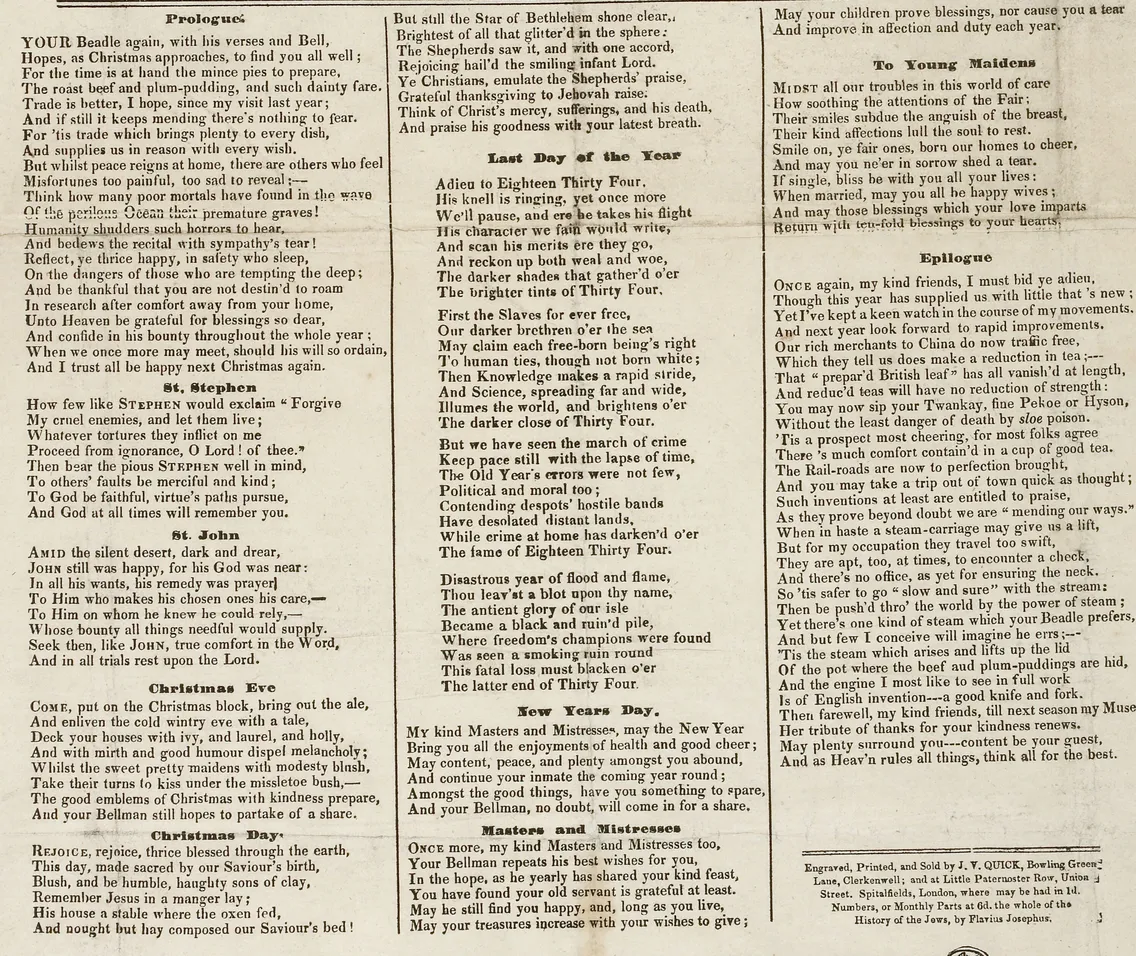

My kind Masters and Mistresses, may the New Year

Bring you all the enjoyments of health and good cheer;

May content, peace, and plenty amongst you abound,

And continue your inmate this coming year round;

Amongst the good things, have you something to spare,

And your Bellman, no doubt, will come in for a share...

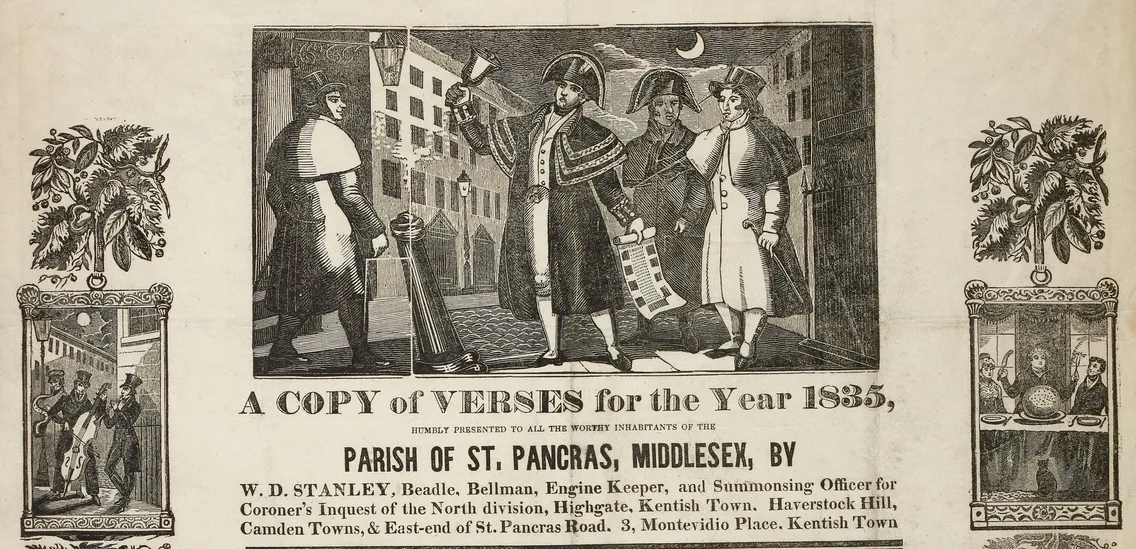

Published in 1835 London, this broadside – currently in our collection – was presented to "all the worthy inhabitants of the Parish of St Pancras" during the time between Christmas and New Year.

London service workers and seasonal verses

The holiday season brought forth a unique tradition that dated back to at least the 1700s: service workers would distribute beautifully crafted broadsides such as this one to remind residents of their year-round contributions.

These workers included bellmen who made public announcements, lamplighters who kept streets illuminated, beadles who assisted with parish services, and dustmen who maintained cleanliness. Many workers performed multiple roles across different local authorities, forming the backbone of community life. Their daily efforts ensured the smooth operation of London society in the 1700s–1800s, from maintaining well-lit streets to delivering important news and keeping neighbourhoods clean.

These essential workers often faced challenging conditions, working through harsh weather and long nights to keep their communities functioning properly. The nature of their work meant they became familiar faces in their neighbourhoods, developing personal relationships with the residents they served throughout the year.

The art of asking for tips

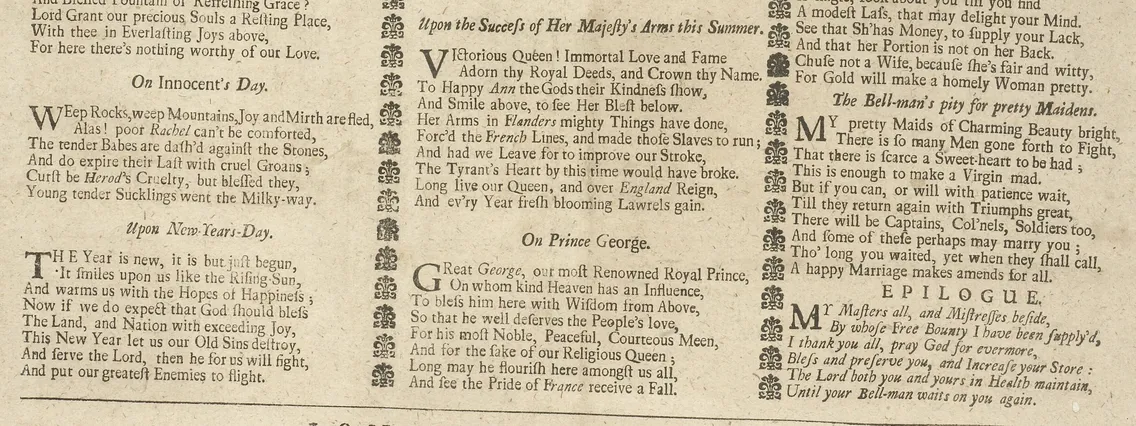

The broadsides themselves evolved from simple woodcuts to elaborate engravings. This is one of the oldest examples of such broadsides from 1706. It shows a charming illustration of a bellman and his dog, accompanied by verses for each day from Christmas Eve to the New Year, and then beyond.

“The Year is new, it is just begun, it smiles upon us like the rising sun, And warms us with the hopes and happiness...”

The same basic designs would be repurposed yearly, with parishes customising the verses and illustrations to their needs. They referred to their ‘masters’ with the hope of receiving a “bounty” or tips and praised their ‘mistress beside’ for her beauty and good virtues.

These broadsides represented more than just requests for gratuities; they were artistic works that showcased the period’s printing techniques and design aesthetics. By 1832, these prints featured sophisticated designs with domestic scenes and classical motifs, often created by established printers like JV Quick of Clerkenwell.

These broadsides represented more than just requests for gratuities, they were artistic works that showcased the period's printing techniques and design aesthetics. The verses were carefully crafted to appeal to the householders' sense of generosity while highlighting the workers' dedication to their community.

Many of these broadsides were so beautifully designed that families might have preserved them awhile, serving as reminders of the community bonds they represented.

A community-building custom

These weren't mere requests for money – they were an integral part of the holiday atmosphere. Service workers would often recite their verses while walking the streets, adding to the festive spirit. The broadsides themselves became decorative pieces, with households displaying them as seasonal artwork. This practice helped strengthen the bonds between service providers and residents, creating a sense of shared community values.

The tradition fostered a mutual understanding between different social classes, acknowledging the interdependence that kept London's society functioning. During the holiday season, these interactions helped bridge social divides and create a more cohesive community spirit.

A dustman's handbill warning people in the district of fake lamp-lighters.

The tradition of holiday tipping became so established that it even attracted imposters. In a handbill from December 1830, also published by JV Quick, warns residents about fake lamplighters requesting Christmas boxes, taking advantage of people’s seasonal generosity.

Ancient origins of holiday gift-giving

This broadside from 1761 has religious motifs on the border, and different themes for each of the verses.

This tradition of giving during the festive season still exists in old neighbourhoods, but how far back do such customs go?

The practice of giving gifts during the winter holidays traces back to the Roman empire. The Romans celebrated 1st January by honouring Janus, the two-faced god of transitions who gave January its name. They exchanged presents, hosted festive banquets and gave special coins bearing Janus’ image to honour Strenia, the goddess of New Year’s gifts.

“The endurance of these customs across millennia demonstrates how deeply rooted gift-giving and celebration are in human culture”

While religious authorities sometimes frowned upon these pre-Christian customs, the traditions were so deeply embedded in society that they eventually merged with Christian celebrations. These old customs laid the foundation for many of our modern holiday traditions, particularly the practice of expressing gratitude through gifts and celebrating with communal feasts.

The endurance of these customs across millennia demonstrates how deeply rooted gift-giving and celebration are in human culture. And these scenes are depicted in the broadsides, for instance one dating back to 1829.

The evolution of holiday gratuities

'The Gasman's Arms' broadside (1823–1840) and a border of woodcuts representing the gas industry.

Today's service providers rarely distribute decorative broadsides or recite verses, and the practice of holiday tipping has become less common. Perhaps this shift reflects our changing relationship with community service workers – as our interactions become more automated and distant, we've lost some of that personal connection that made the tipping tradition so meaningful.

Modern readers might recognise parallels between these historical practices and our own holiday customs. We still gather for festive meals, exchange gifts and celebrate the transition from one year to the next – much like the Roman and Victorian Londoners. While the specific traditions may have changed, the core values of gratitude, community and celebration continue to define our holiday season.

These broadsides in our collection remind us of the importance of acknowledging those who contribute to our community’s wellbeing. Perhaps, reminding us that we might consider how to adapt their spirit of personal connection and gratitude to strengthen our own community bonds today.

Mariarosa Spanu is Project Assistant at London Museum.