21 December 2021 — By Danielle Thom

Tiles of London, from Londinium to today

From Roman Londinium and 18th-century coffee houses to modern-day Tube stations, London has been home to a vibrant and varied ceramic tile industry for centuries.

“The tile is as old as London itself”

The humble ceramic tile is something we take for granted as we walk around London. It’s there on the facades of buildings, in Tube stations and public bathrooms. Little squares and rectangles in neat little rows, so commonplace that we barely notice them as we rush to and fro across the city.

But what we probably don’t realise, is that the tile is as old as London itself – Roman tegulae, or tiles, are some of the clearest proofs that we have for the layout of Roman Londinium (50–410 CE).

“It was between the 1870s and 1920s that London became a tiled city on a grand scale”

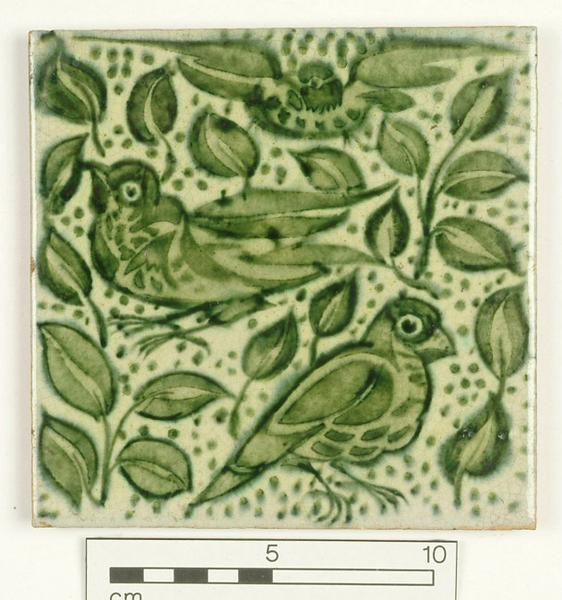

Elaborate patterned tiles were used on the floors of high-status medieval buildings, such as priories. By the Tudor period (1485–1603), hand-painted tin-glazed tiles were being imported from Delft, in the Netherlands.

These were used to line fireplaces and hearths, and their cheerful blue and white designs must have been an attractive sight in the flicker of firelight.

‘The Tile Kilns in Maiden Lane, Kings Cross’, watercolour by M Row, 1838.

South bank was a centre of tile-making

London became a centre of English tile-making in the 17th and 18th centuries, particularly along the south bank of the Thames at Lambeth, where pottery had been produced since the Roman period. It was here, in 1815, that the firm of Jones, Watts and Doulton – eventually, just Doulton – was established.

At a time when most large-scale ceramic production had moved out of London to Staffordshire, Doulton remained in the capital. Their financial success came from the manufacture of industrial ceramics – sewage pipes and bathroom fixtures, for a city increasingly aware of the need for sanitation (particularly in the aftermath of the ‘Great Stink’ in 1858). But it was their art pottery that captured the imagination. Alongside decorative vases and other vessels, the Doulton factory at Lambeth produced architectural tiles for both interior and exterior use.

Among the most notable of their works was a series of tiled plaques for the Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice in Postman’s Park, commemorating individuals who had lost their lives while saving others. They were at the forefront of changing fashions in design, from the 1870s until the factory’s closure in 1956; part of the factory building survives today on Lambeth High Street, decorated with the firm’s own tile designs.

The Memorial to Heroic Self-Sacrifice in Postman’s Park, London.

Tiles reflecting a colonial, orientalist mind set

It was in the half-century between 1870s and 1920s that London became a tiled city on a grand scale. Simple to produce in bulk, and easy to clean and maintain, tiles offered a way to produce striking yet practical architectural designs for a relatively low cost.

“In many ways, tiles enabled the modern city to function and grow as an imperial capital”

At the height of the British empire’s reach and power, tile design frequently reflected a colonial, orientalist mind set, appropriating ‘exotic’ styles from Arabic and Asian cultures. The ornate tiled bath house at Bishopsgate (1895), or the ‘Arab Hall’ of Leighton House (1877), decorated with genuine Iznik tiles from Persia, are surviving examples which can be viewed today.

The tiled Victorian Bath House in Bishopsgate, London.

In many ways, tiles enabled the modern city to function and grow as an imperial capital. Victorian and Edwardian Londoners could enjoy a drink in one of the newly tiled pubs springing up across the capital, such as The Ten Bells in Spitalfields; or purchase their dinner in the magnificent tiled food hall of Harrods’ department store, decorated by Doulton in 1902.

Heading home via the Underground (perhaps to a newly built house with a tiled kitchen and bathroom), they might pass through one of Leslie Green’s iconic stations, tiled in oxblood red outside and elegant glossy green inside.

Swimming pools, hospitals, restaurants, shops, public transport – all of the amenities and institutions of the modern city, clad in tiles.

Tile watching on the London Underground

The Russell Square station with Leslie Green’s iconic oxblood red tiles on the outside and glossy green tiles inside.

London’s transport network, in particular, has developed as an important site for showcasing the best and most unusual tiling work. Some stations are so well known as to be instantly recognisable – Sir Eduardo Paolozzi’s vivid tile mosaics at Tottenham Court Road, say, or the Sherlock Holmes silhouette tiles adorning Baker Street.

“Leslie Green’s designs have paved the way for tile installations by some of London’s best and most innovative ceramicists”

Others may be less well-known, but still brighten the commutes of thousands of Londoners each day, such as the perspective-bending Elliptical Switchback mural (2010) at Hoxton Overground station. Leslie Green’s designs have paved the way, more than a century later, for tile installations by some of London’s best and most innovative ceramicists.

Matthew Raw’s ‘Panel Discussion’ (2016) is one of a series of works by the ceramicist which engages with the idea of the urban street grid.

Jacqueline Poncelet’s monumental Wrapper (2012) covers part of Edgware Road station, with a series of tile murals reflecting the history of the area, while Matthew Raw’s handmade tiling for Seven Sisters station (2017) works on a more intimate scale. Raw’s work, which explores the potential of tiles to connect with a sense of place and belonging, is also in London Museum’s permanent collection.

Panel Discussion (2016) is a quartet of three-dimensional terracotta tiles, adorned with a quotation from Henry Mayhew, the social reformer and author of London Lives and the London Poor (1851): “He knew that this was London. England was in London somewhere, but he did not know where.”

The quotation is spelled out in delicate, hand-formed clay lettering, an integral part of the tiles themselves. The tile becomes a time capsule, something durable and solid which connects us with Londoners of a century ago.

Another contemporary work in the museum’s collection, Laura Carlin’s History of London (2016), takes this idea literally. A huge mural composed of 678 individual tiles, it illustrates a whimsical version of London’s past from prehistory to the present day. It invites us to look closely, and pore over each individual tile for fear of missing some crucial detail. A reminder, as we walk the streets of London, to look up and around ourselves, and enjoy this city of tiles.

Danielle Thom is Curator of Making at London Museum.