21 December 2022 — By Finbarr Whooley

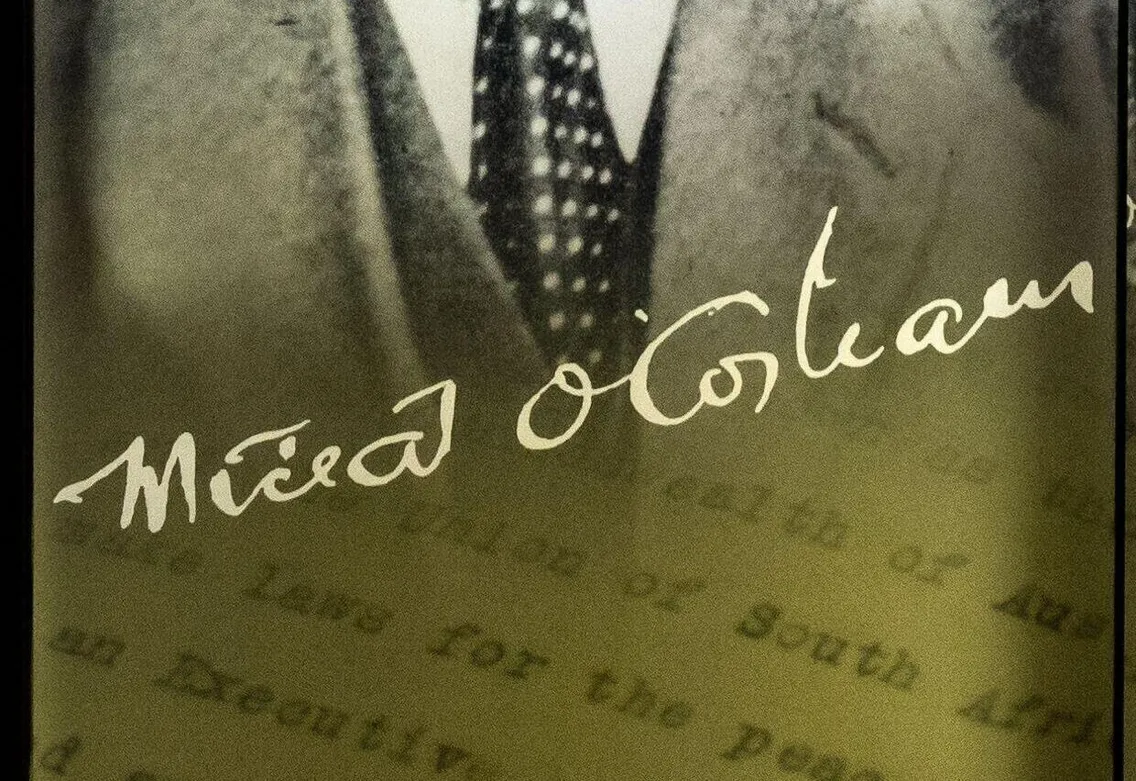

The mystery of Michael Collins’ signature

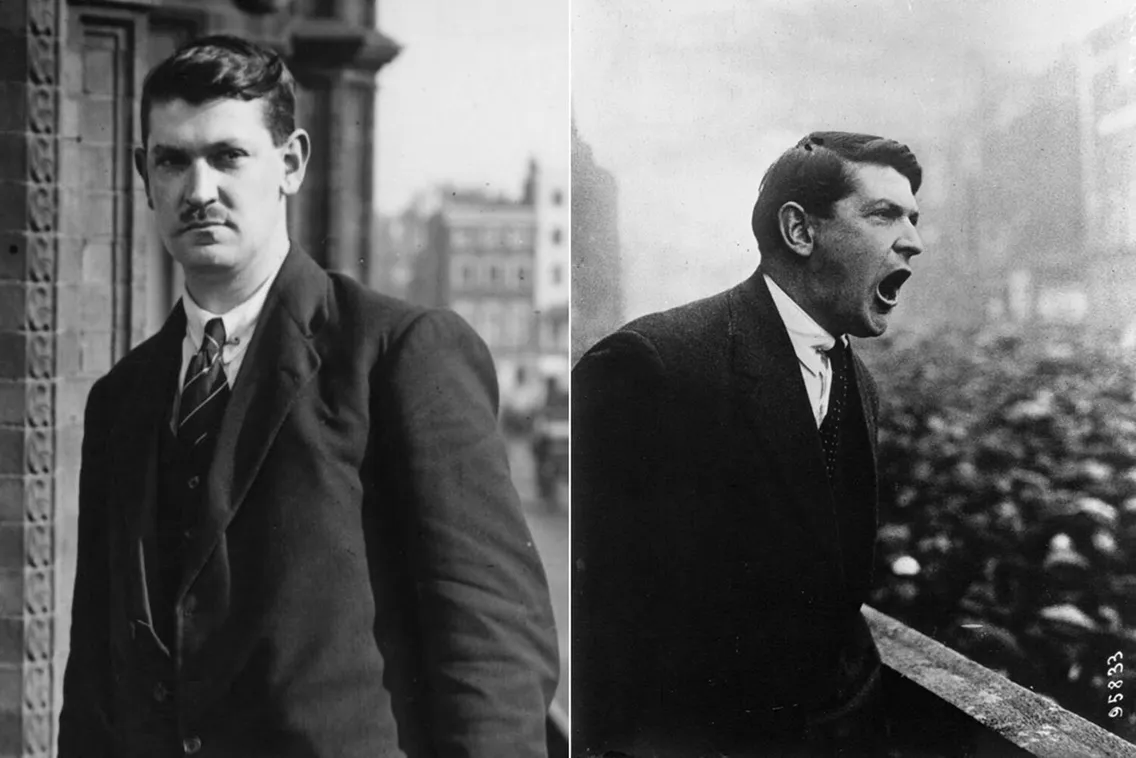

Did you know that one of Ireland's most famous revolutionaries became radicalised in London? Portrayed by the media of his day as a dangerous gunman and a romantic playboy, Michael Collins, the IRA leader, learned it all while living in London.

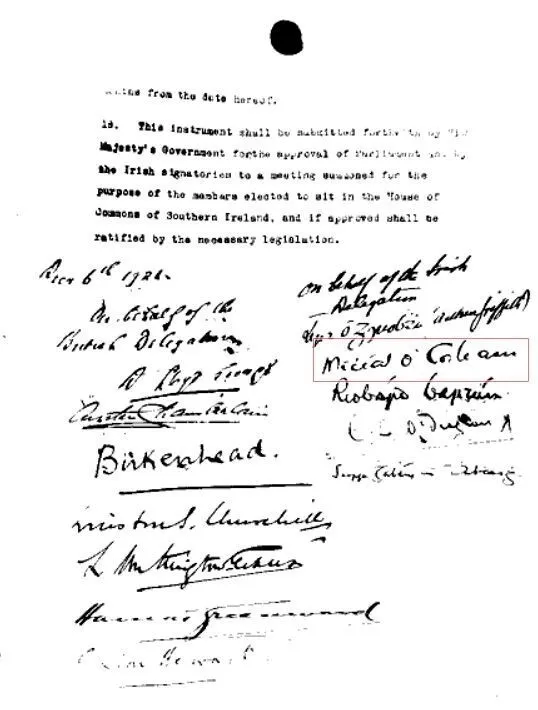

On 6 December 1921, Michael Collins, the Irish revolutionary leader, put his signature to the historic Anglo-Irish Treaty. Later, he wrote to his fiancée Kitty Kiernan that he had signed his death warrant. Within eight months that prediction had come true. Collins was assassinated on 22 August 1922, during the bitter civil war that engulfed Ireland following the signing of the treaty.

Michael Collins' signature: A historical insight

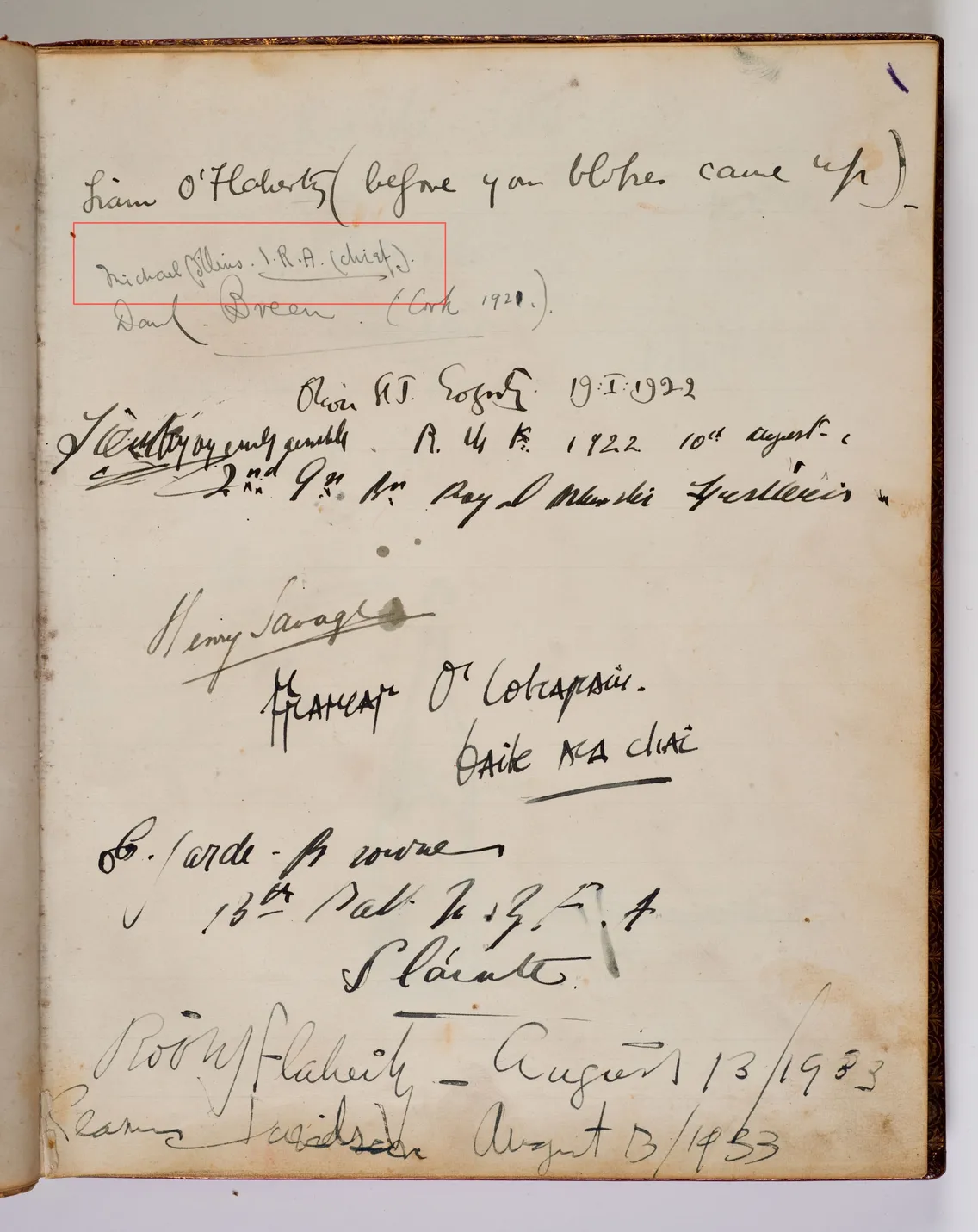

When I discovered that the museum owned a visitors book of the famous Fitzrovia Restaurant de la Tour Eiffel on Percy Street containing a signature of Michael Collins, I was intrigued. Interestingly, it was signed during the period Collins was in London negotiating the peace treaty.

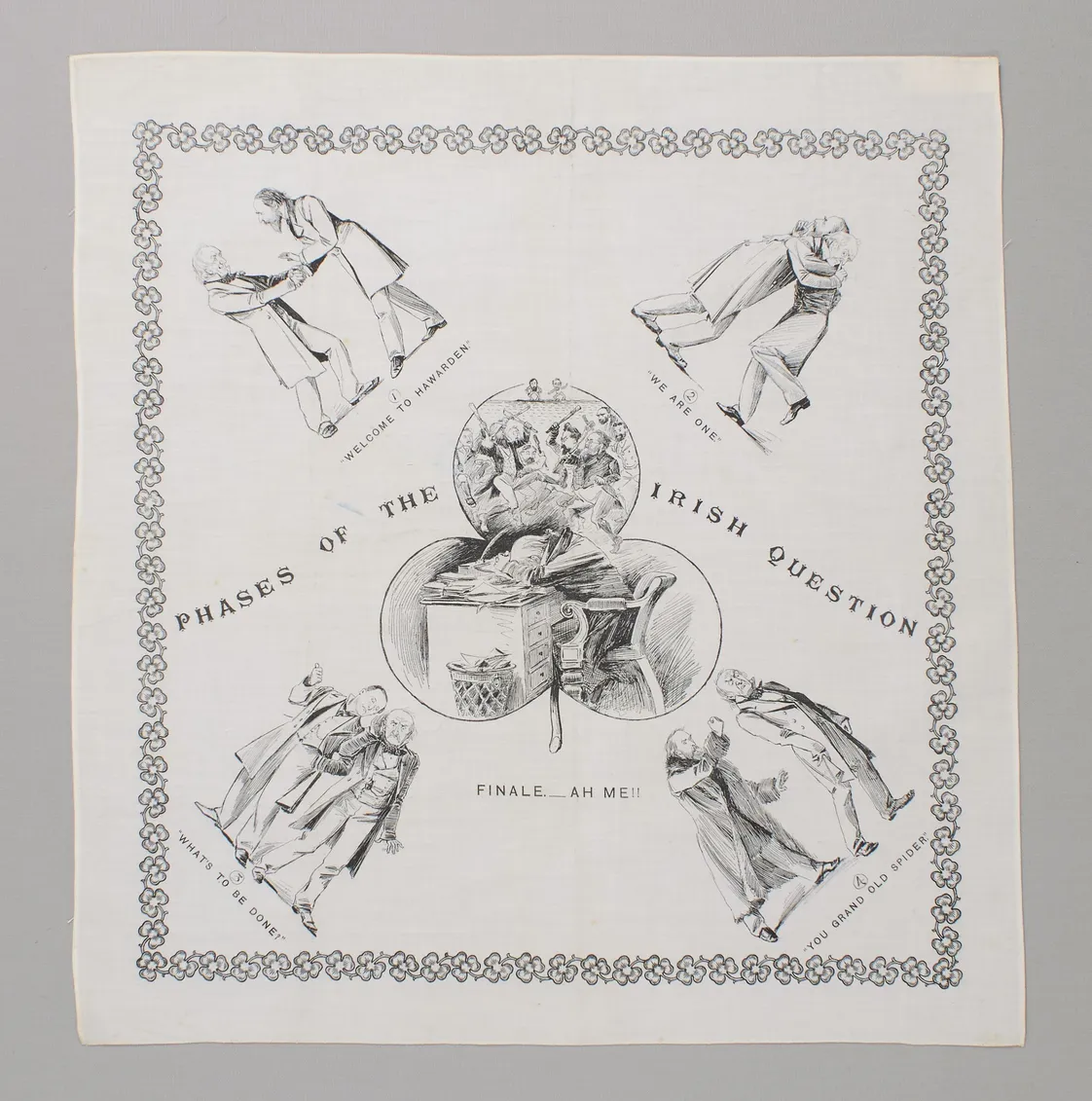

The years 1916–1922 were traumatic for Anglo-Irish relations. Following an initially unsuccessful rebellion, the Irish Republican Army (IRA) fought a deadly guerrilla war against the British security forces. Eventually, British public opinion forced the government to enter into peace talks with the rebels. Between October and December 1921, a high-powered government team led by David Lloyd George, and including Winston Churchill, faced an Irish team led by Arthur Griffith and Collins.

The Irish delegation in London

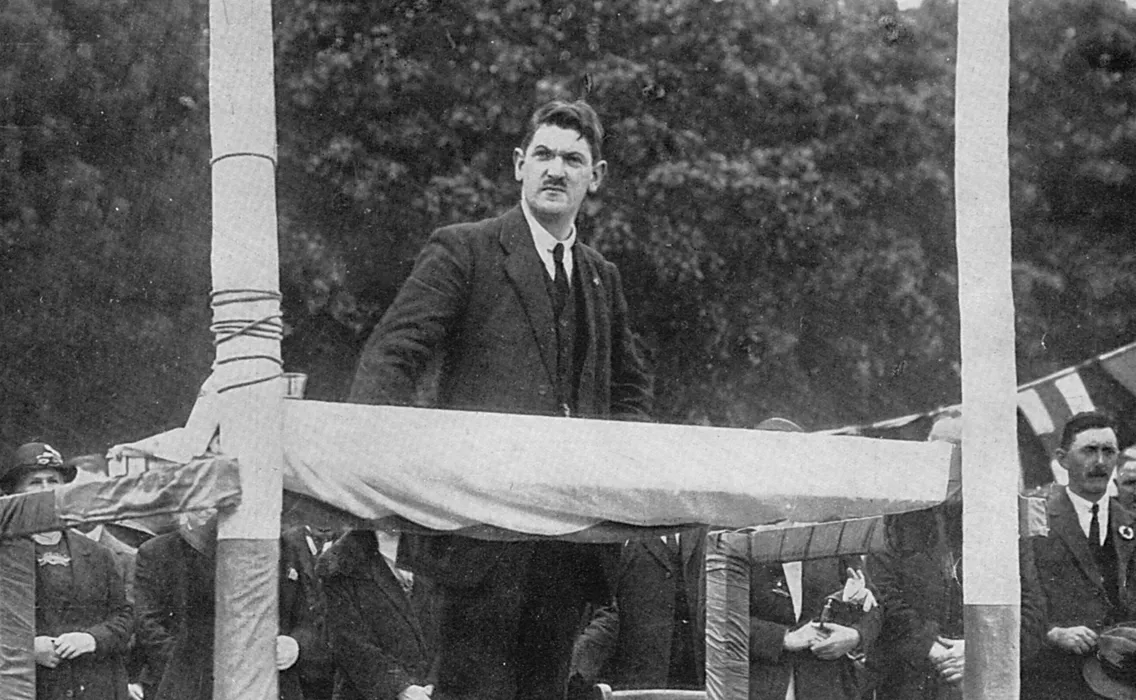

Upon arrival in London in October 1921, the Irish delegation became the focus of media attention. Crowds gathered to see them and they were invited to social events, house parties and public performances. Collins was particularly in demand because the media portrayed him as a dangerous gunman.

We know from contemporary accounts that members of the delegation went out in the evenings. And they might have visited the trendy Tour Eiffel during that time. The restaurant’s visitors book, now in the museum’s collection, contains signatures of celebrities of the day such as actor Charlie Chaplin, writers Aldous Huxley, Nancy Cunard and playwright Noel Coward. The restaurant was particularly associated with a school of painters called the Vorticists. An undated signature, which seems to have been written towards the end of 1921 proclaims “Michael Collins IRA (chief)”.

Did Collins take time out from the stressful treaty negotiations to eat in one of the most artistic venues in the capital? After all, he was known to have an interest in the arts and he was no stranger to London.

Collins and London

Collins was 16 upon arrival in London in 1906. His job was that of a ‘boy clerk’ in the Post Office Savings Bank in West Kensington. London represented a place of opportunity and freedom for the young migrant, who had little chance for advancement in rural Ireland. He spent the formative years of his life here. London was the place where he learnt about theatre, the world of finance and where he met a wide range of people, both Irish and non-Irish. London also radicalised the young Collins.

There was a vibrant Irish cultural and sporting scene in Edwardian London. Collins played Hurling for the Geraldine Club in Notting Hill, and regularly attended Irish cultural events and social gatherings. In November 1909, he was sworn into the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB) in Barnsbury Hall Islington. The IRB was a revolutionary organisation, which aimed to overthrow the British presence in Ireland.

London’s influence on revolutionary leaders

During this period, London was host to radicals from across the world. Perhaps the most infamous were the Latvian anarchists who engaged in a shoot-out with police and military in the Sidney Street siege of 1911. A famous image from that siege, which is in our collection, shows a young Winston Churchill, then the Home Secretary, peering around a corner during the gun battle.

Intellectuals, thinkers and revolutionaries travelled to London to study and to meet other like-minded people. M.K. Gandhi studied in London between 1888 and 1891, and the young Ho Chi Minh lived there for several years, from 1913 onwards.

When he was about 20, Collins left the Post Office to work at a firm of City stockbrokers Horne & Co. In those years, Collins the revolutionary was also Collins the commuter, travelling by public transport each day from Kensington to Moorgate.

London plaques marking the stay of revolutionaries such as M.K. Gandhi (Kingsley Hall), Ho Chi Minh (Haymarket) and Michael Collins (Netherwood Road).

Easter Rising in Dublin

Collins left London in 1916, the year of the Battle of the Somme. London was on a war footing; the Zeppelin attacks occurred from 1915 onwards and thousands of young Londoners were away at the front. However, for Collins and many young Irish men and women, the focus was not on France but on Ireland. For them, this was an opportunity to wrestle Ireland free of British rule.

He left his employers, the Guaranty Trust Company in January, telling his colleagues that he was going to “join up”. They assumed that he was joining the army and paid him an extra week’s wages as bonus. In reality, he was going to Dublin to participate in the Easter Rebellion.

“By the time of the treaty negotiations in 1921, these men were hardened guerrilla fighters”

The rebellion of 1916 left hundreds of people dead and Dublin in ruins. The leaders were executed and scores of activists, including Collins, were imprisoned across the UK. Collins spent many months in Frongoch camp in Wales. When the young revolutionaries were eventually released in a general amnesty they emerged even more determined to lead a successful revolution. By the time of the treaty negotiations in 1921, these men were hardened guerrilla fighters.

The visitor’s book mystery

The Tour Eiffel visitors book contains two closely written signatures – undated but apparently for the year 1921. One is Michael Collins, followed by the words IRA (Chief) and the second is Daniel Breen, Cork 1921. Breen was a local IRA commander in County Tipperary. Directly below these names is the signature of Oliver St John Gogarty, a noted writer, doctor, politician and wit. He was a contemporary of James Joyce, who based his Ulysses character Buck Mulligan on him. He supported the Irish revolution and was a friend of both Arthur Griffith, president of Sinn Fein, and Michael Collins. Collins had a key to Gogarty’s house in Dublin, which was one of the many safe houses he used when evading British security forces.

While I could not find any reference to Breen in London at this time another theory was developing: could Gogarty have been in London and hosted a meal at the restaurant for his friend Collins?

But then I discovered that while Gogarty’s signature appears to be genuine, the same can’t be said for Collins. The Irish nationalist always signed himself as ‘Mícheál Ó Coileáin’. Indeed, that is how he signed the Anglo-Irish treaty document. Looking at this English version of the name and closely comparing it to authentic examples of his signature convinced me that this signature is a forgery.

“Who might have forged it and why?”

The signature was clearly known to other diners during the subsequent history of the restaurant. In August 1933, the famous American filmmaker Robert Flaherty dined there with the crew from his Irish fictional documentary Man of Aran (1934). While Flaherty’s companions signed their names in the appropriate page, he returned to the page from a decade earlier that contained the Collins signature and other famous Irish people like Gogarty and Irish writer Liam O’Flaherty.

This would suggest that restaurant staff were proud of the signature and drew it to diners’ attention, no doubt it would be of great interest to some of their more radical clientele. Did the staff fake the signature back in 1921, or perhaps did Collins actually eat there and the staff added his name to remind everyone later?

Trying to unravel the signature mystery

There is a sad connection between the signatures of Collins and Gogarty. Within eight months of the signature being written, Gogarty – acting in his capacity as a medical doctor – examined the body of his assassinated friend and prepared it for lying in state. Michael Collins died following an ambush while travelling in a military convey at a place known in English by the name “the mouth of the flowers” in his native West Cork. He was 32 years old.

In conclusion, we don’t know the answer to the mystery of the Collins signature and a lot more research will be needed before there can be any certainty. We need to look more closely at the other signatures to better understand why so many famous Irish people seemed to frequent the restaurant at this time.

Maybe the public will help us to solve the mystery by studying all the names on the page to see what connections they can make? All suggestions welcome @wearelondonmuseum

Finbarr Whooley is Director of Content at London Museum.