24 January 2024 — By Beverley Cook

The 1889 London dockers’ & tailors’ strikes

In 1889, London tailors and dockers took industrial action protesting working conditions and minimal wages. While the two strikes remained separate, the brotherhood of the strikers led to mutual moral and even financial support.

In the late summer of 1889, east London was the scene of great industrial unrest as workers from two key local industries – tailoring and the docks – fought for better pay and working conditions.

The tailors and dockers were inspired by the strike of the largely young female workforce of the Bryant & May match factory in Bow the previous year. The success of the 1888 match girls’ strike in achieving better working conditions and pay showed how a united front by unskilled and impoverished workers could, with public support become a force for change. The dockers’ and tailors’ strikes during August–September 1889 also reflected the growing influence of unions that encouraged mutual support of strikers across different industries.

Why did the London dockers strike?

London’s casual dock labourers had long protested against the humiliation of the foreman’s early-morning ‘call-on’ that forced desperate crowds to gather at the dock gates, in the hope of a few hours’ work. Strikes became increasingly common as more workers joined unions, including the Dock, Wharf, Riverside and General Labourers’ Union led by Ben Tillett.

On 12 August 1889, unions issued a set of demands to the private dock companies that included minimum 4 hours’ work when taken on “without favouritism” at call-on times fixed at 8am and 12 noon. The demand for increased rates of pay to be 6d or ‘tanner’ (around £2 now) per hour for day work with 8d per hour overtime resulted in the strike being referred to as the ‘dockers’ tanner’. The inevitable refusal by the employers to concede resulted in a walk out across the port. Within days, skilled stevedores and lightermen unusually joined their unskilled brethren in the strike and, with up to 75,000 dockers refusing to work, the port was completely paralysed. As the world’s shipping queued in the River Thames unable to discharge its valuable cargo, London’s pre-eminent reputation as the “warehouse of the world” was at risk.

Realising the importance of public support and media interest in their fight, the dock unions organised daily processions to the financial heart of the City of London with brass bands and banners. Mass meetings led by union leaders on Tower Hill attracted thousands of onlookers. Locals, many of whom depended on the docks for their livelihood also rallied to support the strikers. This included the Irish landlady of the Wade’s Arms pub in Poplar, who provided a meeting room for the union leaders and nourishing stews to energise their struggle.

Donations were crucial for sustaining the strike and paying for the daily relief food tickets handed out by the union to the strikers. The fear of starvation was regarded by the dock companies as a powerful weapon in their favour. But as news of the strike wired around the British Empire, a lifeline came to the London dock workers in the form of a huge donation of £30,000 (over £2 million now) from the Australian labour movement and dockworkers’ whose livelihoods also depended on the successful operation of the London docks. This amount also went on to contribute to the tailors’ strike happening simultaneously.

A handwritten note on black mourning paper, probably written by a striking docker, listing the demands of the dockers.

The devastating economic impact of a paralysed port of London on the profits of the Empire prompted the Lord Mayor of the City of London to open negotiations between the dockers and dock companies. Also involved was Cardinal Manning, the Archbishop of Westminster, reflecting the Irish Catholic heritage of many working and living in the Docklands area. The agreement conceded most of the dockers’ demands, including the ‘dockers tanner’. On 15 September, the strikers held a victorious rally in Hyde Park, with the Australian flag at the forefront. The following morning, the dockers returned to work, satisfied for now, with their new pay and conditions.

The great strike of London’s tailors

Two weeks into the dockers’ strike, their nearby neighbours in the east London tailoring industry also began industrial action. Similar to the dockers, the tailors were unionised and the strike united 10,000 Jewish tailors from three unions in the fight for improved working conditions.

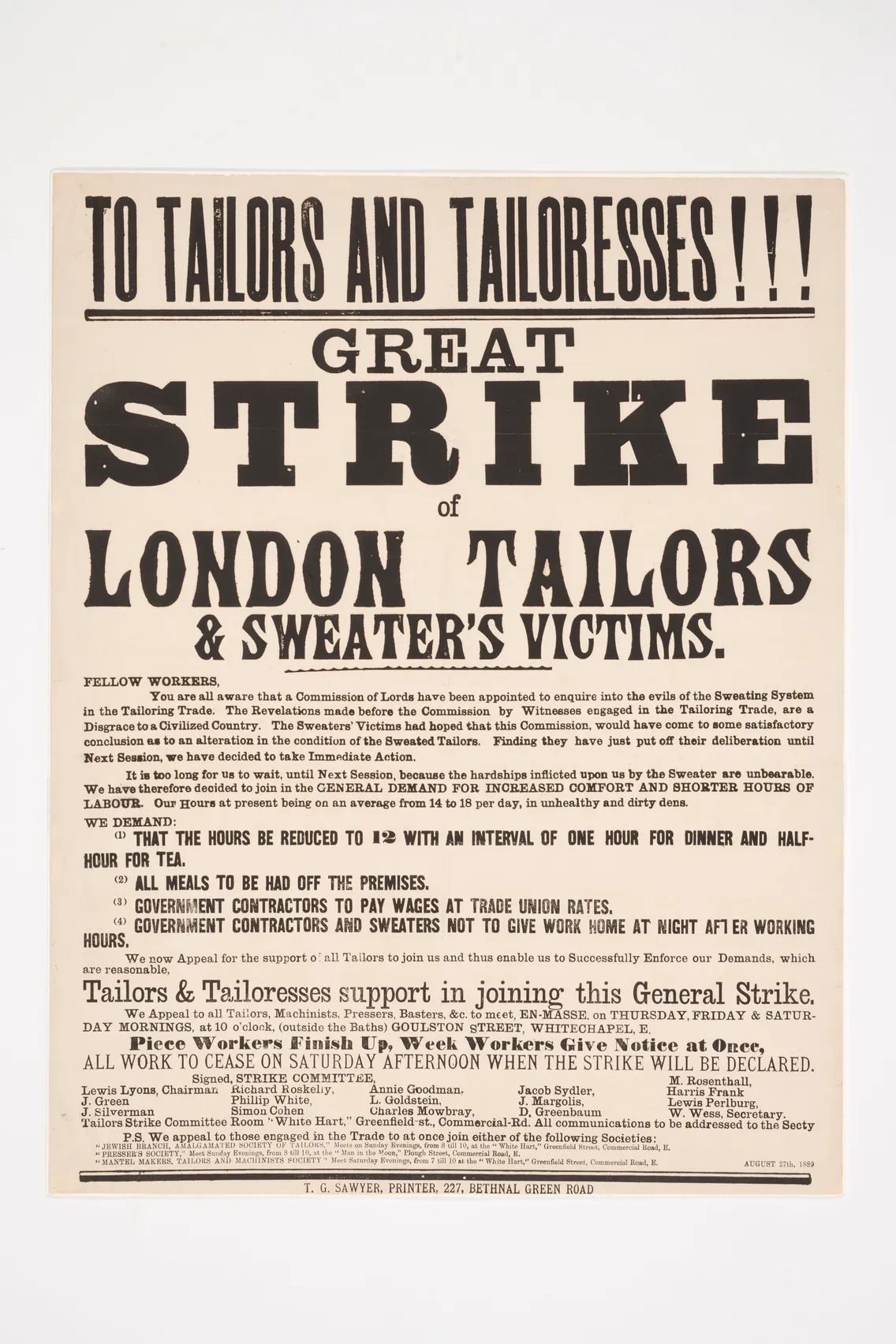

A poster from the 1889 tailors’ strike stating the demands of the workers, including specified work timings and wages at trade union rates.

By the 1880s, up to 70% of adult Jewish immigrants living in the Whitechapel area worked in the clothing industry dominated by the ‘sweating’ system of small workshops and the subdivision of labour into unskilled or semiskilled tasks. Charles Booth’s Inquiry into the Life & Labour of the People in London (1889), identified 571 workshops making men’s coats in less than 1 sq. mile in and around Whitechapel. Most employed less than 10 workers confined for long hours in cramped workrooms.

The tailors’ strike demands included a fixed 12-hour working day with an interval of 1 hour for dinner and tea to be taken off the workshop premises, increased wages at trade union rates and the abolition of the practice of forcing workers to take work home.

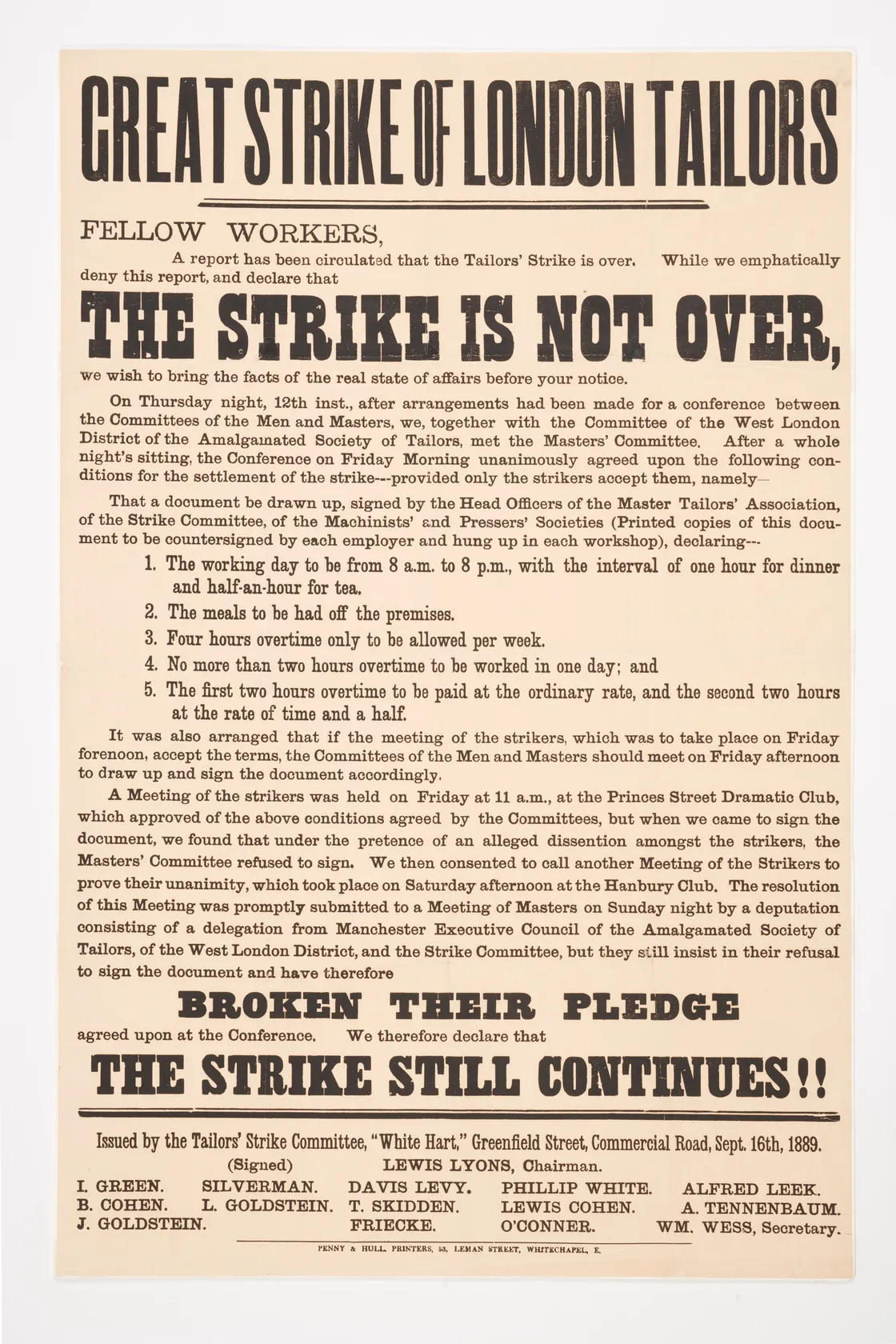

Both the dockers’ and tailors’ strikes benefited from effective and motivated leadership. With Ben Tillett and Tom Mann fighting the dockers’ cause, the tailors were roused by Lewis Lyons, Chair of the strike committee, and the Lithuanian Jewish anarchist William Wess who acted as Secretary. Both strike committees used local pubs for their headquarters. The tailors based at the White Hart Pub in Greenfield Street, from where they kept strikers informed through posters printed in English and Yiddish pasted around the Whitechapel area.

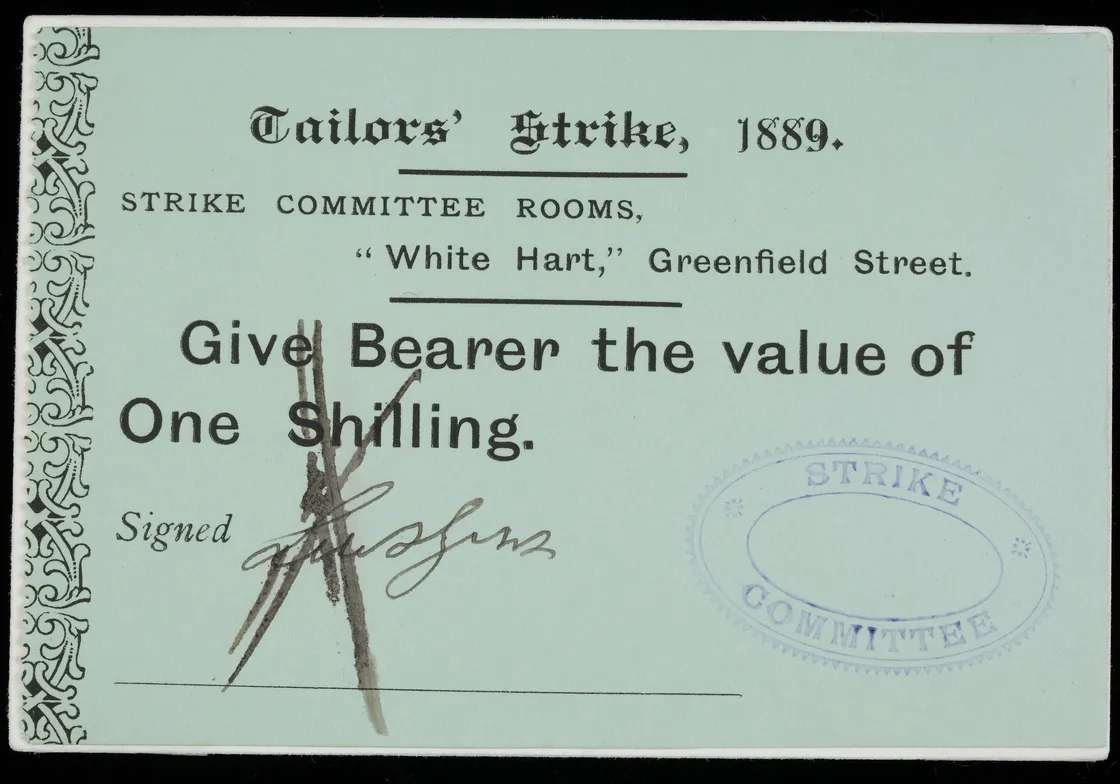

The strike committee raised funds to support the striking workers and provide them with essential food, issued in the form of food coupons such as this one.

Strikers in arms: Dockers and tailors

Although the two strikes remained separate, the brotherhood of the strikers led to mutual moral and even financial support. The donation from Australian workers to the dockers also benefited the tailors, who received £100 (around £8,000 now) from the Australian fund to pay for relief food tickets.

Notably, both strikes were finally resolved through the negotiating skills of independent and prominent society figures trusted by both sides. Acting as mediators between the tailors and the master tailors were leading members of the Anglo-Jewish community, including Lord Rothschild and the local Orthodox Jewish Member of Parliament, Samuel Montagu. The final negotiated agreement successfully achieved many of the key strikers’ demands for fixed working hours and a limit on overtime.

As the tailors returned to work after five weeks, a Yiddish periodical noted: “The workers are learning unity in action, and are moving step by step towards their self-realisation as a class.”

This observation could equally apply to the dockers and match girls, with all three strikes marking a small, but significant shift in the balance of power between employers and a unionised workforce.

Beverley Cook is Curator, Social and Working History, at London Museum.