07 February 2022 — By Jelena Bekvalac

Testy teeth! Dental interventions in 19th-century London

Of the 20,000 skeletons in our collection, we look at three sets of teeth, which provide fascinating insights into 19th-century dentistry.

This page contains content some people may consider sensitive, or find offensive or disturbing. Understand more about how we manage sensitive content.

Your teeth say a great deal about you and are a wonderful source of information. They show effects of childhood diseases, malnutrition, dental injury, food and drink — with sugar having the greatest detrimental effect (as many of us know).

London Museum has a remarkable collection of over 35,000 skeletons recovered from archaeological excavations. The skeletal remains and teeth of these people provide a unique understanding about the lives of the people and extraordinary changes to London over the years. Dental interventions found during such excavations form only a small part of such a large collection. The reason could be that dental treatments were expensive and not readily available to all. Studying their teeth gives us a unique glimpse into their lives, the time period they lived, their socio-economic status and access to dental treatment.

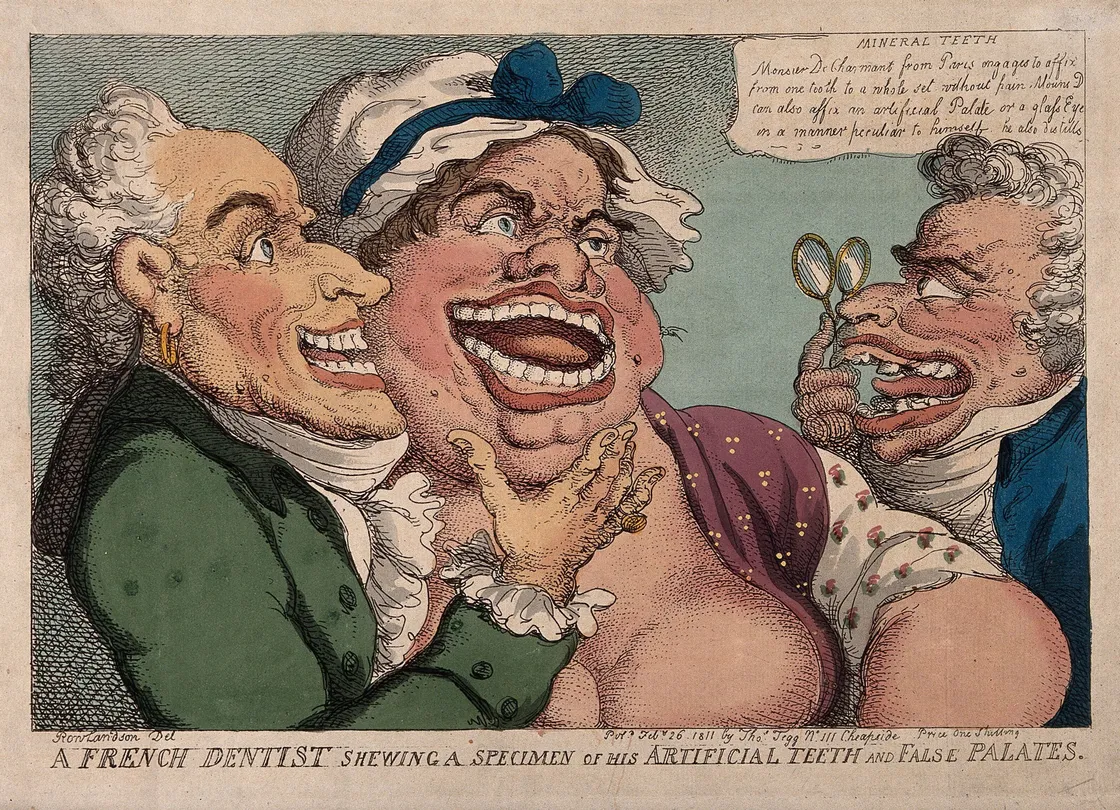

N Dubois de Chémant demonstrating his own and a woman's false teeth to a prospective patient. Coloured etching by T Rowlandson, 1811.

A brief history of dentistry

There have been discoveries of dentistry and dental treatment reaching as far back as the ancient Egyptians, Greeks, Etruscans and Romans, with texts in Sumerian, Egyptian hieroglyphs and Greek giving fascinating details. Evidence revealed from a discovery in Italy identified one of the earliest dental treatments with a tooth filling – 14,000 years ago.

But, it was many centuries before dentistry was seen as a distinct profession. French surgeon Pierre Fauchard (1679–1761) – known as the ‘Father of Modern Dentistry’ – led the way with his 1728 publication Le Chirurgien Dentiste (The Surgeon Dentist). It outlined a system for caring and treating teeth for the first time, with Fauchard also introducing the idea for dental fillings, using dental prosthesis (false teeth, bridges, dental plates). He proved that it was the acids from sugar that led to tooth decay. Prior to this, ‘tooth worms’ were the designated culprits.

Teeth of a male from the medieval period, coming from the excavations of St Mary Spital, Augustinian Priory, during development of the Spitalfields Market.

In England, renowned surgeon John Hunter (1728–1793) greatly influenced how dentistry was seen as a profession, notably with the publication of his 1771 book The Natural History of the Human Teeth.

During the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries, there were major advances made in dental treatment, including materials used for fillings (gold, silver and amalgam), porcelain teeth, use of animal teeth and even other people’s teeth. Dentures were made from wood, animal bone, ivory and vulcanite, to present-day plastics and acrylics.

Why were dental treatments important?

While the reasons for dental problems might be many, the most common are severe tooth decay and cavities. Treatment has always been an expensive affair. In the past, dentistry would have been accessible to those with money, since expensive materials such as gold and ivory were used. People living in poorer socio-economic conditions did not have the luxury of cosmetic dental treatments. The only form of treatment, if affordable, would be to have their rotten teeth extracted.

Good teeth were a commodity that could be sold – extracted both from the dead and the living (for some extra money).

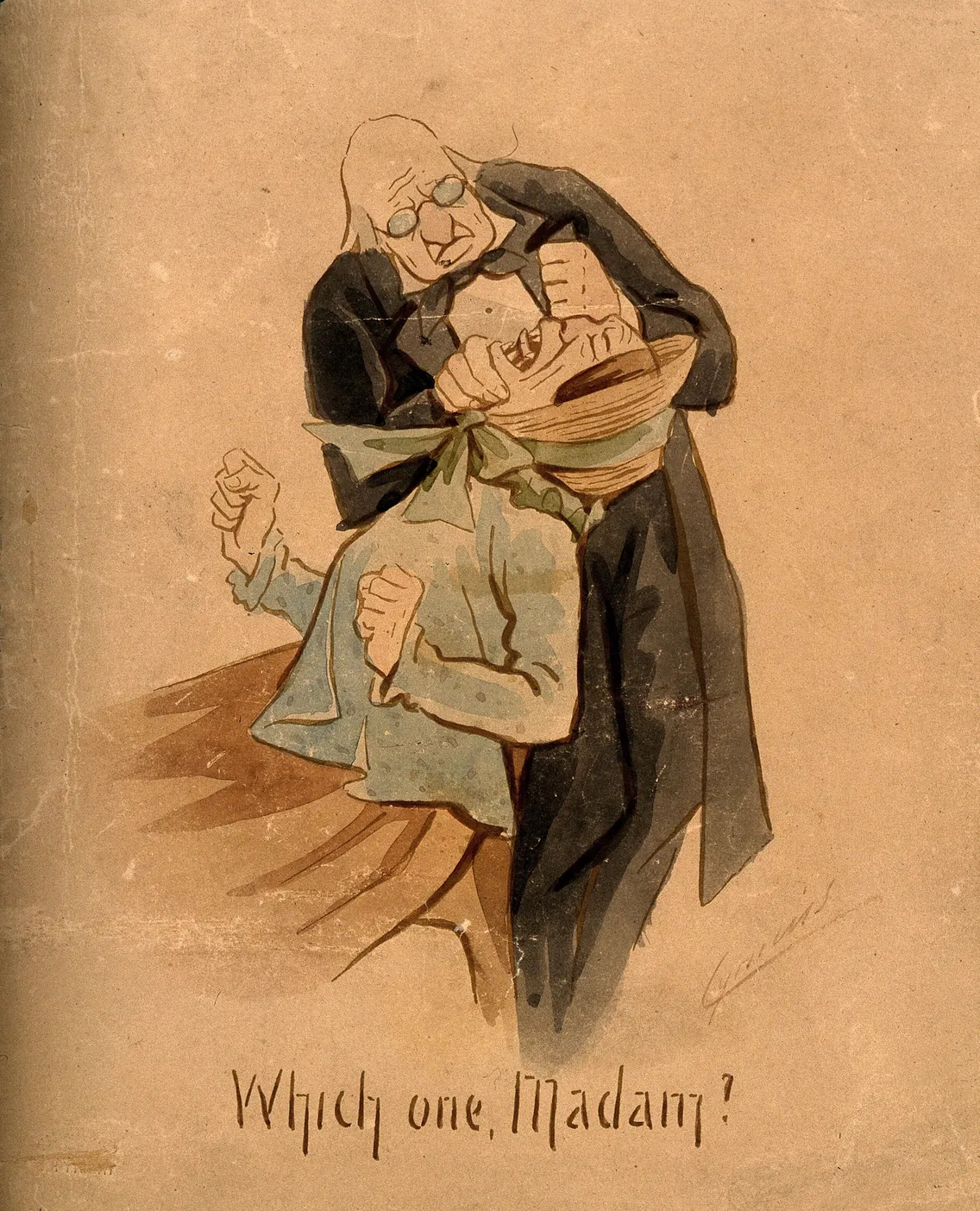

A fashionable dentist's practice. Teeth are being extracted from poor children in order to create dentures for wealthy people. Coloured etching after T Rowlandson, 1787. Rowlandson, Thomas, 1756–1827.

The man with the gold filling

Interestingly, the first gold filling to be recorded within the museum’s skeletal collection was found in a male, 36–45 years old, excavated during the development of the site that had been the location of St Bride’s lower churchyard, Fleet Street.

The lower churchyard was the burial place for the poorer people of St Bride’s parish, and was associated with Bridewell workhouse and the debtor’s jail. This burial ground was consecrated in 1610 and established to cope with the overcrowded burial conditions outside the church that upset the wealthier parishioners congregating there.

For this male skeleton to still have the tooth in his upper jaw with the gold filling intact, was quite something. Especially since it was quite common for such precious fillings to be removed from the deceased and sold.

Unfortunately, with no coffin plate, it wasn’t possible to know who he was or exactly when he died. The area of the excavation of the burial ground was dated 1770–1849, so it can only be surmised that he lived and died during this period, and at one point in his life had been wealthy enough to be able to pay for a gold filling. Not to forget his pain tolerance, since a gold filling procedure could be lengthy, but imagine it with none of the numbing agents used in today’s procedures. Later in life, he could have lost his wealth, ending up at the debtors’ jail, and eventually at the burial ground at St Bride’s lower churchyard.

The British Dental Association Museum has examples of the different types of instruments used for treatment and filling. Gold was an excellent material with it being inert and, so, not harmful being in the mouth.

Squalid living conditions of Victorian London

Prior to the development of a new nursery at St John’s Church of England Primary School in Bethnal Green, an archaeological excavation was carried out under the school’s playground in 2011. It was found that it was a privately owned burial ground during 1840–1855.

In the mid-1800s, London was undergoing a population boom and industrialisation. This part of east London was one of the poorest and disadvantaged parishes in London. Following the excavation, 1,033 individuals were recovered; and from the analysis of their remains, they provided an incredibly vivid insight to the squalid living conditions of Victorian London. Many showed more than one disease process through their lifespan. Poor dental health was common, as well as a high rate of tooth loss.

The woman with a partial denture

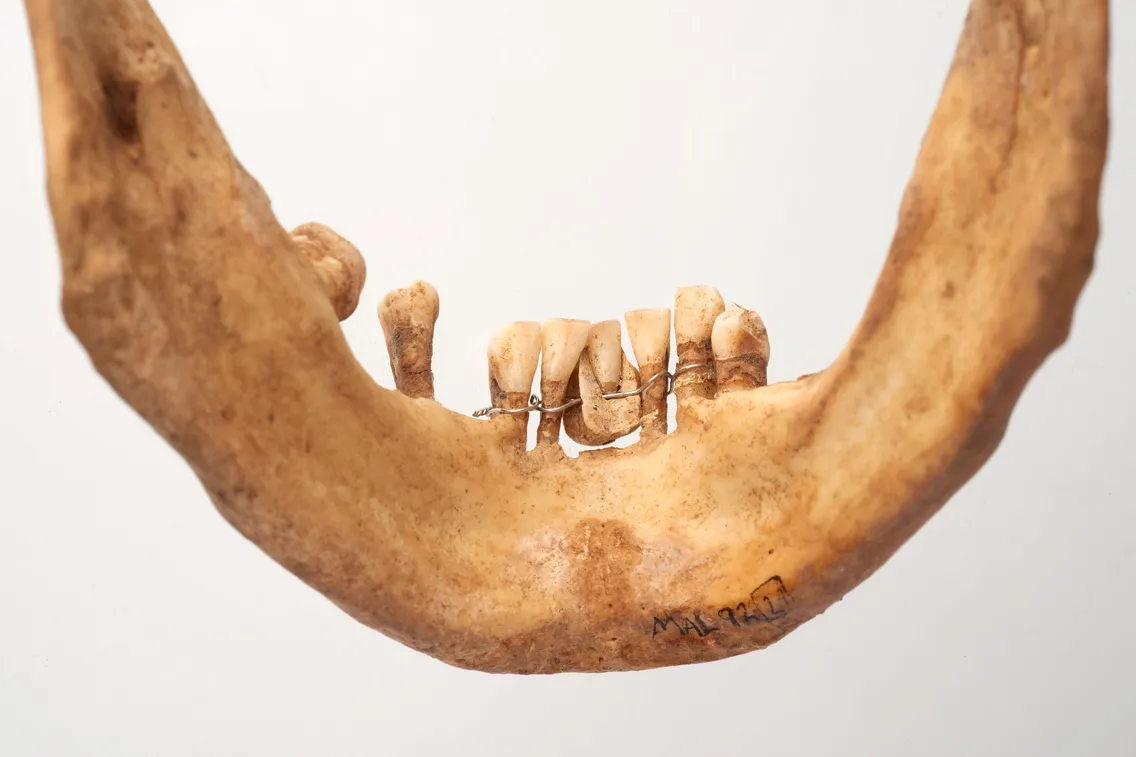

Among the individuals excavated, was an elderly female with a partial denture made not of gold but a cheaper alloy metal, potentially with lead content. The partial denture on the left upper jaw has been fitted to the area of the jaw moulding to where teeth are both present and missing, with metal polls to hold teeth. The two front teeth (central incisors) have metal adhering to the back of them to keep them in place, as part of the denture. The teeth used to make these dental interventions would once have been in the mouth of another person.

Such dental work would have incurred a cost, but one that the female must have been able to pay. It obviously functioned and worked in filling the gap but being metal in her mouth, it might not have been always pleasant.

Charlotte Bampton Taylor’s ‘Waterloo tooth’

The term ‘Waterloo teeth’ is associated with the removal of teeth from the many fallen soldiers who died during the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, then used in dentures and bridges. At the time, bodies and teeth were often sold by those known as Resurrectionists, or body snatchers. With so many having unfortunately died in the battle it was an opportunity for those willing to gather large quantities of teeth to sell. It would not just be ‘dentists’ buying teeth, but also jewellers and blacksmiths, who worked with them to fashion ‘dental creations’.

In 1817, St Marylebone church was initially built at a location that would gradually see expansion of housing developments for the socially affluent in west London. Excavations in the grounds of the church in 1992 revealed a number of burials, some with associated coffin plates. One such individual who had been interred in a crypt vault in an expensive coffin was Charlotte Bampton Taylor, who died in 1837, aged 77, and had dental treatment that would have been expensive at the time.

In the area of her front teeth in her lower jaw, Charlotte has a dental bridge with a ‘Waterloo tooth’ held in place with platinum wire. The ‘Waterloo tooth’ has a bone disc/plug to keep it in place, with the platinum wire attaching it to the adjacent teeth. It is possible to see grooves in the teeth, indicating that it must have been in place for quite some time, and it’s also possible to see the effects of periodontal (gum) disease and the loss of molar teeth. The one molar remaining slopes at an angle to compensate for the loss of the other molars on the left side. Presumably Charlotte did not want a gap in her teeth and the intervention may have been more for cosmetic reasons.

Thankfully, we’ve come a long way and we don’t need other people’s teeth to make dentures and bridges any more, but materials can be fashioned and moulded to look like real teeth. The cost can be very high in achieving the perfect set of gnashers and glowing white teeth! In that, there is very little difference from days of yore.

Jelena Bekvalac is Curator of Human Osteology at London Museum.