02 April 2018 — By Dr June Purvis

Suffragette Christabel Pankhurst & her ‘militant’ strategy

June Purvis, author of ‘Christabel Pankhurst: A Biography’, spoke to us about the iconic campaigner Christabel Pankhurst and her role in securing votes for women.

Who was Christabel Pankhurst?

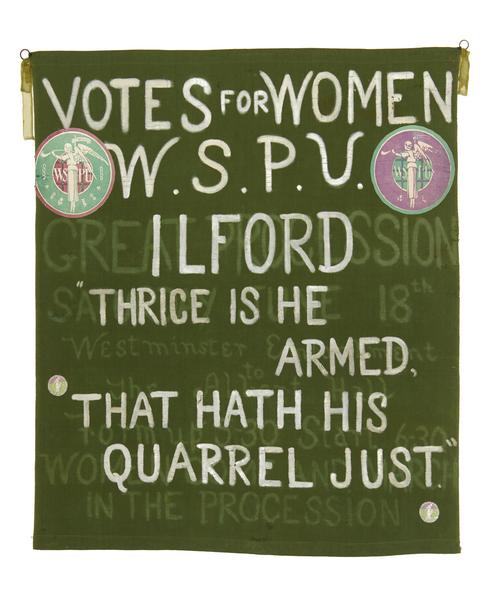

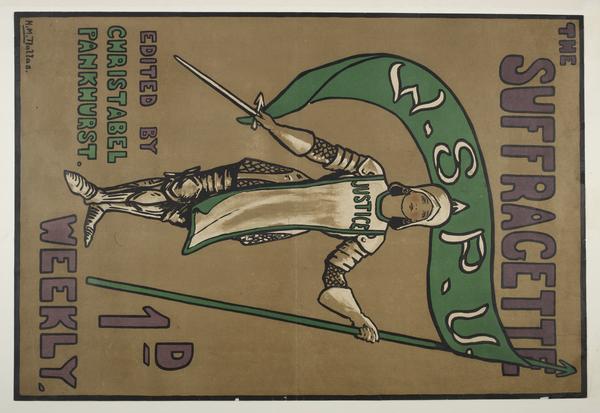

Christabel Pankhurst (1880–1958) was a very influential figure in the Suffragette movement in Edwardian Britain since she was the co-leader, with her mother Emmeline, of the Suffragettes of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). The WSPU had been founded in October 1903 by Emmeline, Christabel and some local socialist women, at the Pankhurst home at 62 Nelson Street, Manchester. Christabel became the Chief Organiser and key strategist of the WSPU. In later life, Christabel converted to Second Adventism and in 1940 moved to the USA, where she became a successful preacher and wrote about the Second Coming of Christ. However, it is for her suffrage work that she is remembered.

What inspired you to write a biography of Christabel?

Christabel has been very much maligned by historians, especially by her younger sister Sylvia, whose influential 1931 book The Suffragette Movement has become the dominant narrative of the campaign and Pankhurst family life. Sylvia was a socialist feminist who wanted to ally the WSPU with the socialist movement while Christabel, who resigned her membership of the Independent Labour Party, wanted to keep the WSPU free from affiliation to any of the men’s political parties of the day.

In her book, Sylvia presents a hostile picture of Christabel, their mother’s favourite child. Writing as a rejected daughter, a jealous sister and an angry socialist she presents Christabel as right wing, elitist, ruthless and autocratic. I had read enough in the primary sources to question this portrayal, which has been accepted unquestioningly by most commentators. Further, the late Jill Craigie gave me exclusive access to the Suffragette papers she held, particularly papers belonging to Christabel. So all these factors inspired me to research further, and write a biography of this eldest Pankhurst daughter.

“Christabel decided that women had been too submissive and had to become more assertive”

How different were the tactics of the Suffragette movement compared to previous campaigners for votes for women?

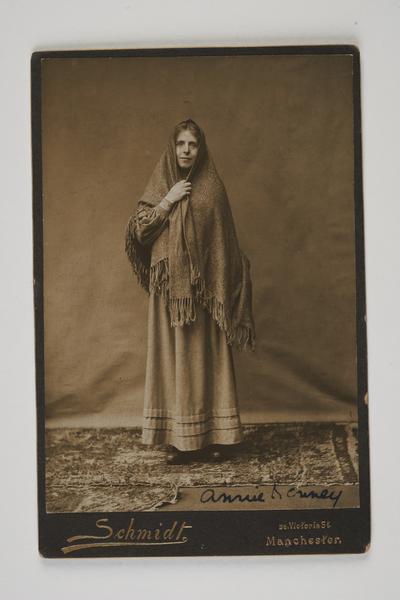

We must not forget that women had been campaigning for the parliament vote for women from at least 1865, using constitutional, peaceful methods such as writing to MPs, and presenting an annual petition to Parliament. This had brought no success. Christabel decided that women had been too submissive and had to become more assertive about their democratic rights, which she called a ‘militant’ strategy. Thus, together with Annie Kenney a working-class recruit to the WSPU, she initiated in 1905 the tactic of heckling MPs and a willingness to go to prison for the cause.

Christabel and Emmeline had tensions over tactics with the other Pankhursts. Why was that?

In October 1912, when the vote had still not been granted, Christabel and Emmeline decided to escalate the scale of militancy, which would include damage to property. This was a reaction to the violence the suffragettes had encountered on 18 November 1910 when, on a peaceful demonstration, they were treated with exceptional brutality by the police as they tried to push them back from reaching Parliament Square. Many of the assaults on the women, on ‘Black Friday’ as it became known, were of a sexual nature. The injured women said to Emmeline Pankhurst – what was the point of suffering damage to their bodies when protesting peacefully if the smashing of a window brought about a quicker arrest without physical assault.

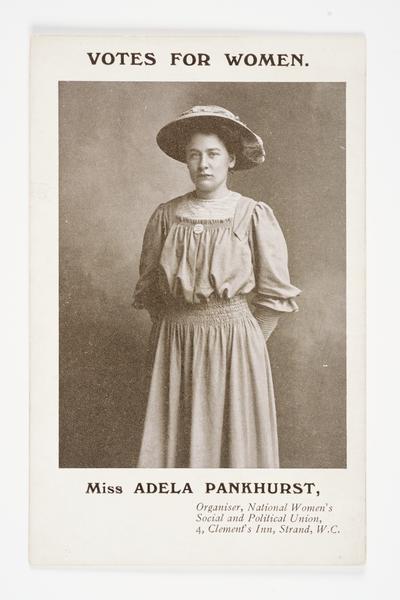

Thus, window smashing was engaged in, as well as attacks on pillar boxes and setting fire to empty buildings, as a way to force the Liberal government of the day to give women the vote. Throughout this campaign, both Emmeline and Christabel emphasised that there should be no danger to human life. However, both Sylvia and Adela, the youngest Pankhurst daughter, disagreed with this escalation in vandalism. Since Sylvia allied her East London Federation of the Suffragettes to the socialist movement, contrary to WSPU rules, she was expelled from the WSPU in 1914.

Emmeline also thought, erroneously, that the unhappy Adela was planning to establish a rival organisation to the WSPU and so suggested to her that she start a new life in Australia. Adela welcomed the proposal as a way to get out of a difficult situation. So the WSPU’s policy caused rifts in the Pankhurst family. No exceptions could be made for relatives. The same rules that applied to the membership applied to sisters and daughters.

“More than one Suffragette emphasised how Christabel put the fight into women”

You also wrote an earlier biography of Emmeline Pankhurst. In the course of writing your new book, did you change your opinion of her?

No, I did not change my opinion about Emmeline who was a courageous, determined and inspiring leader of the WSPU. She was always in the thick of the action and suffered 13 imprisonments which played havoc with her body. Sylvia in The Suffragette Movement portrays her mother as a weak leader, led astray by Christabel. This is nonsense. Both Emmeline and Christabel were charismatic leaders, and powerful orators who were always in accord with each other.

What drove the suspicion between Christabel and the broader left-movement in the UK? What do you think about suggestions that the WSPU was campaigning on behalf of middle-class women?

Let’s face it, the Independent Labour Party (ILP), despite saying that it upheld sex equality, did not practise it. Christabel found early on that sexism was rife in the ILP – socialist men could be just as unjust to their womenfolk as middle-class men. Time and time again, Labour MPs gave priority to class issues rather than women’s enfranchisement.

The WSPU sought the parliamentary vote for women on the same terms as it was or would be granted to men – that is on a property qualification – since they wanted to break the sex discrimination that prevented women from voting. Christabel knew that a claim for a universal franchise for all men and women would not be granted by Herbert Asquith, the Liberal Prime minister for much of the suffrage campaign, and a fierce opponent of votes for women. And she was right on this.

The 1918 Representation of the People Act, which was passed after Asquith had stepped down and was succeeded by David Lloyd George, was a very cautious measure. It only enfranchised certain categories of women aged 30 and over – those who were householders, wives of householders, occupiers of property of £5 or more annual value, and graduates. Universal suffrage was not on the cards.

Nor were the nearly 8.5 million women who were enfranchised granted the vote on the same terms as men. Under the 1918 Act men could vote at the age of 21, without any property qualification – and even younger if they had seen active service in the war. Women had to wait until 1928 before they could vote on equal terms with men, without any property qualification.

Do you think women could have won the right to vote in 1918 without Christabel and the WSPU?

No. More than one Suffragette emphasised how Christabel put the fight into women, encouraging them to develop their backbone. She emphasised that the subordinate position of women in Edwardian society was due to the power of men and so she saw the separatist WSPU, which only admitted women as members, as an important vehicle for women to foster a sense of sisterhood that would enable them to stand on their own two feet and articulate their demands.

Why do you think it has been so long since the last biography of Christabel Pankhurst was published?

As a feminist, Christabel pioneered a number of concerns that were later central to ‘radical feminism’ in the Second Wave of the women’s movement, in the 1960s and 1970s. These concerns included the power of men over women in a male-defined world, the importance of a women-only movement as a means for raising women’s consciousness, the commonalities that all women share, and the primacy of putting women first rather than considerations of social class, political affiliation or socialism.

Such concerns were of little interest to a left-leaning women’s history as it developed in the UK. It was the socialist Sylvia Pankhurst who was admired, not Christabel, and it was Sylvia’s book The Suffragette Movement which became the standard reading of events. Since feminism was seen (and still is) as owned by those on the left, she became a ‘problematic figure’ in the history of British feminism.

Committed to a cause rather than party politics, Christabel was despised by the left, disliked by the Conservatives and hated by the Liberals. There was no political party to claim her as a ‘heroine’. Few were interested in her life and even fewer were keen to write a biography about her.

Why do you think it's important to remember the struggle for women's suffrage?

It is important to remember the struggle for women’s suffrage since it was a struggle for women’s right to be able to exercise the parliamentary vote in our democratic system. That it was a long, hard fight in which women experienced brutal treatment, imprisonment and forcible feeding is no credit to the Liberal Government of the day, nor to the male MPs who consistently voted against a women’s suffrage measure.

Dr June Purvis is the author of Christabel Pankhurst: a Biography.