02 February 2025 — By Tim Miller

Struck gold: A mother-son mudlarking adventure on the Thames

From child hobbyist to Thames mudlark society Chair, one man's 50-year journey of riverside treasure hunting with his mother reveals London's hidden history – including a gleaming Roman gold coin discovery.

“As I leant forward and plucked the coin from the mud, it was unmistakable – gold!”

We’re all familiar with the chocolate money populating the Christmas stockings of small children: sweet treats wrapped in shiny gold foil masquerading as mint condition coins. As I scoured the Thames foreshore, one day in the early 2000s, that’s what appeared to be staring up at me – a coin too pristine and too perfect to be real.

If it wasn’t chocolate, perhaps it was one of those replicas you can buy in a museum shop.

But as I leant forward and plucked the coin from the mud, its weight was unmistakable – gold!

The gold Roman coin of Emperor Diocletian.

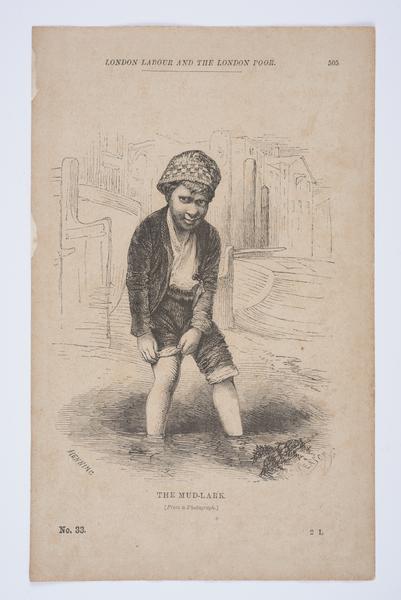

Mudlarking: A window into the past

The stunning condition Roman aureus (coin) of Emperor Diocletian (274–315 CE) was my best single find. And it was a very long wait. I’d been mudlarking since the 1970s and had lost count of the number of times onlookers had shouted in a mocking tone from the riverside walk: “Struck gold yet?”

Now, after nearly 30 years, I finally had.

But it wasn’t gold that had lured me onto the foreshore. I was at primary school and doing a project on Roman London. My mum Pamela and I had been cycling around the City photographing remnants of the original Roman wall when I spotted a ‘digger’ on the South Bank. He’d found a mixture of coins and bottles, and I was excited at the possibility of doing the same.

So, after he’d left for the day, I sat in his hole running the thick mud through my fingers. Blessed with beginner’s luck, I found a fragment of metal that turned out to be a broken Victorian florin (2 shillings). It was broken because it was a contemporary forgery made from silver and lead.

“This was a window to 19th-century criminality. I was hooked”

This very first find wasn’t a mass-produced artefact – but a window to 19th-century criminality. I was hooked.

Most weekends as a 10-year-old, if the tides allowed, I was on the foreshore alone. This was the 1970s, so none called social services. The stretch I was searching on was generous: coins, rings, pipes, although nothing of great age, mainly Victorian. But the finds were sufficiently abundant to tempt my mum into joining me.

The mother-son mudlarking duo

Tim’s mother Pamela mudlarking and digging with full gusto on the Thames foreshore, 1989.

The mother-and-child double-act must have been a rare sight, as mudlarking in those days was almost exclusively a male pursuit. We didn’t ‘dig’ but still had a fair degree of success as eyes-only surface scrapers.

There was much excitement when my mum unearthed what London Museum initially thought was a rare medieval pilgrim’s bell. Later tests revealed it to be much more modern Indian silver. But the ‘mystery’ and uncertainty only added to the excitement.

Contributions to historical records

The only picture from the pre-selfie era of a young Tim Miller mudlarking, about 2005.

As a teenager in the mid-80s, I was by now a recognisable foreshore face. Inevitably, I was invited to join the Society of Thames Mudlarks – an elite group of ‘veterans’ licensed to dig deep holes and to assist London Museum with their excavations. Members were renowned for being the most skilled in using metal detectors and were asked by the museum to assist in ‘rescue’ digs in the City of London.

The finds unearthed by society members on excavations and the foreshore enormously contributed to our understanding of the lives of ordinary Londoners so often overlooked by the historical record.

“In the 80s and 90s, my mum was in her 60s and unfazed by the hard labour of digging on the foreshore”

In the 80s and 90s, my mum and I briefly teamed up as ‘diggers’. She was by this stage in her 60s, unfazed by the hard labour but sometimes barely able to climb out of our holes because of her diminutive stature.

I had to create bespoke steps carved into the sides to ensure she could clamber out.

A silver bell that was initially thought to be medieval pilgrim bell.

Society of Thames Mudlarks

Since the society was founded in the 1980s, mudlarks have needed a permit from the Port of London Authority (PLA) – issued on condition that all finds be reported to and recorded with London Museum. The number of mudlarks in the society who are permitted to ‘dig’ is capped at about 50.

The PLA also issues several thousand ‘standard’ permits for non-diggers who need to report and record their finds. These days there are much tighter restrictions on where and how deep society members can go. Despite this, as Chair of the society, I can proudly report that members continue to assist the museum by providing a pipeline of exciting discoveries.

Tim mudlarking on a cold January morning on 2025.

My favourite mudlark finds

Over the last few decades, I have returned to surface searching. My favourite finds include a leather Tudor jerkin, a hoard of 12 medieval groats (silver coins), an Elizabethan toy gun, a plague medicine bottle and a 17th-century pocket sundial.

I also found a rare Roman medallion probably given to a soldier or an official as a mark of honour to commemorate a special occasion. I’ve come a long way since that primary school project on Londinium.

Although she had moved out of London, my mum continued to mudlark with me. On one occasion she asked me to help dislodge a piece of curved metal from the mud. It turned out to be the handle of something much more spectacular – an 18th-century pewter tankard. It’s elegantly inscribed with the words ‘Hill’s Chop House, at St Mary at Hill” and has a maker’s mark on its base.

This was perhaps my mum’s best find which passed to me on her death last year aged 93. The sandwiches we used to eat with our muddied hands clearly never did her any harm! (But don’t try this at home).

As I reflect on more than half a century of searching the foreshore, I note that what was once a niche and eccentric pastime has become immensely popular – the stuff of bestselling books and primetime TV. But what’s most surprising to me is how long it has taken people to cotton on to the fact that mudlarking the River Thames is the greatest ever hobby.

Tim Miller is Chair of the Society of Thames Mudlarks and a former journalist. Please note that you must have a permit from the PLA in order to go mudlarking.