08 July 2020 — By Anna Laviniere

Stitches in time: Remaking a 1577 Bible cover

How do you recreate the embroidery on a 1577 Bible cover that could have been done by Queen Elizabeth I herself? Here are three stitches and some pointers.

My traineeship at London Museum involves preserving museum objects through environmental monitoring, pest management and other forms of preventative conservation. I also take part in researching and cataloguing collection items.

This article is inspired by my experience of exploring the museum’s embroidery collection and my attempt to recreate elements from one object in particular: a 1577 embroidered Bible that is said to have been to be crafted by Queen Elizabeth I’s own hand.

My enthusiasm for the museum’s embroidery collection stems from my own hobbies. Outside of work and academic study, I am very interested in crafts and textile art. I am a self-taught embroidery artist, sharing my work on my Instagram page ‘Lavystitch’ where I connect with fellow artists and those that admire embroidered work.

Over my two years of stitching, I have learned that embroidery is a very time-consuming and detailed craft. I take this into consideration when admiring textile art, such as the pieces in London Museum's collections.

“Until 1450, all books were entirely handmade and reserved for scholars”

Bible cover ‘worked by Queen Elizabeth’s own hand’

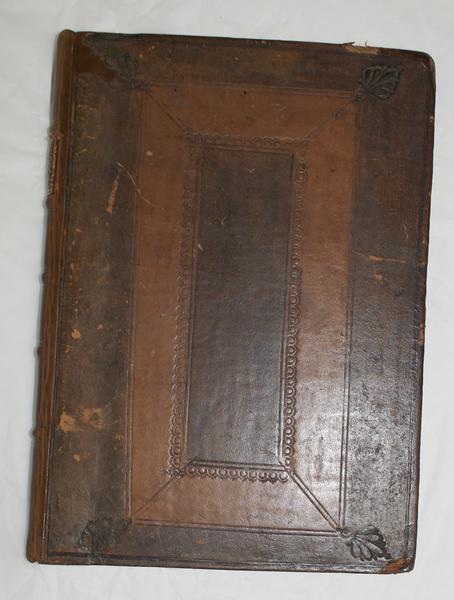

I chose to recreate the 1577 embroidered Bible cover hoping to learn more about embroidery during that time and how it has evolved since. At first sight, I was struck by the materials used in this Bible cover that are thought to be silver-gilt thread, silver purl and small amounts of silk inlaid and couched work. These materials are dramatically different from the cotton threads I commonly find in craft stores and markets for my own embroidery. The luxurious materials used in the making of the Bible suggest that it did indeed belong to somebody with wealth and power, such as a monarch. A letter found at the back of the Bible reads: “This Bible was in possession of the late Duchess of Portland, at her Death it was sold and came into my hands, the covers being worked by Queen Elizabeth’s own hand, whose real Bible it was”. However, the truth of this story requires further investigation.

Bible covers were incredibly precious during the 16th century. Book covers were thought to represent their contents, as well as protecting them, so Bible covers reflected the value placed on the holy words and scriptures they contained. Historically, books were of great worth. Until 1450, all were entirely handmade and reserved for scholars then passed down as heirlooms. This helps us understand the choice of materials for this Bible cover and why it is embroidered; a laborious and esteemed practice.

Materials used by Anna to recreate the embroidery.

Traditional stages in medieval embroidery

I encountered this item while assisting with a tour of the museum’s library, where a selection of books were presented for viewing. The interlacing of Tudor roses and exotic flowers stitched onto the Bible cover make this piece stand out to me. The design is very detailed and complex, compelling viewers to lean in for a better view. On closer inspection, the difference in stitches, thread colour and even thread count is evident. In awe of the sheer arduous detail of the work on the cover, I was inspired to attempt a Renaissance interlace rose design myself.

With the help of Glyn Davies, Head of Curatorial at the museum, and Lucie Whitmore, Fashion Curator, I was able to conduct further research about the traditional stages in medieval embroidery and compare this with modern-day techniques. For example, the first stage in traditional preparation would be termed as ‘pouncing’, which is when the design is drawn onto paper, pricked along the outline and placed onto the grounding fabric. The pounce, which would be a fine powder such as charcoal, would be applied on top of the paper, leaving the design in dotted lines on the grounding fabric to stitch onto. Essentially, a dotted outline of a design.

In the first stage of design in modern-day embroidery, we have access to water and air erasable pens that allow embroiderers to draw designs straight onto the fabric. To trace designs, stitchers may use a lightbox under the fabric and paper, giving them a better view of the outline. Although the process is definitely very similar to imprinting onto fabric, achieving the outline design has become a lot quicker now.

“I used stem stitches, bullion knots and satin stitch to recreate the central Tudor Rose motif of the Bible cover”

Recreating a Bible cover, 500 years later

To recreate the embroidered Bible, I substituted gold metallic thread and yellow thread for the silver-gilt thread. I believe this approach worked just as well in the final look of the piece. As my work comes a few hundred years later than the Bible cover in the museum’s collection, the colours are bound to be brighter and to stand out more than the tarnished gold and silver thread. The original piece has red velvet as the grounding fabric. For my version, however, I chose red cotton fabric to be able to use a water erasable pen for the modern tracing process.

After tracing the design with the water erasable pen, I used stem stitches, bullion knots and satin stitch to recreate the central Tudor Rose motif of the Bible cover.

“The process of sewing the Tudor Rose was very intricate and time-consuming”

The process of sewing the Tudor Rose was very intricate and time-consuming for a 3 x 3 inch design. Comparing this to the scale of the Bible cover indicates how much time the embroiderer would have spent overall on this item. It may have been made as recreation or as paid labour, depending on whether it was a commissioned piece or not. The process has taught me the value of handmade art and what this can add to an object, such as a book. This Bible cover tells its own story which centres on the maker and their visual art.

Embroidery continues to be popular throughout England and around the world. It is both a pastime and profession, which encompasses many different techniques and serves many different purposes. While historically the craft often served a religious purpose, today embroidery is increasingly seen as an act that can be politically powerful. It can also be a self-empowering practice. Through the use of social media, embroiderers can share their experiences and beliefs in thread and potentially reach a global audience. My experience at London Museum has made me reflect on the history of my craft and the people involved, by learning through remaking.

Design for Tudor rose embroidery.

Make your own embroidered Tudor rose

If you would like to have a go at making your own Tudor Rose, you can print or trace the design below and get sewing!

Tools required: Needle, gold metallic and yellow thread, water soluble marker, red cotton fabric, scissors and embroidery hoop of your preferred size (4-inch hoop used here).

You are, of course, free to use any stitch you would like to complete this pattern. But if you would like guidance, here is a step-by-step tutorial showing each of the stitches I used.

Stem stitch

Follow the steps for the Stem stitch.

Commonly used for flower stems. We will use this stitch a lot in the design.

Step 1

Bring the needle and thread through point A and into point B. From the other side of the fabric bring the needle through to point C. Point C should be in the middle of A-B.

Step 2

Bring the needle through to point D. Make sure that C lies on top of A and B. As you go along, all of the following stitches will lie on top of their previous stitch.

Step 3

Bring the needle in through D and out through B, making sure that B is halfway between C-D.

Continuing these steps successfully, here is a final image of stem stitch, this will be used for the outline of the Tudor flower.

Bullion knots

Follow these four steps to make a Bullion knot.

This is another key embroidery stitch when creating floral designs. In this pattern we will use bullion knots to fill in the outline we created with the stem stitches.

Step 1

Bring the needle through point A and into B, this will be the length of your knot. When pulling the needle through point B, make sure not to pull all the thread through for the next step.

Step 2

Bring the needle out through A again and use the thread you did not pull through (Step 1) to wrap around the needle. The distance of the wound thread should be equal to A-B, to help measure this you can tilt the needle slightly (as shown in the image).

Step 3

Hold the wrapped thread with one hand and pull the needle out with the other. Keep pulling the needle until the wraps are flat on the fabric, as shown in the image. Rearrange any wraps as required to make them even, then feed the needle back through point B.

This is a final image of a bullion knot. This should be used in rows to fill the flower pattern.

Satin stitch

Satin stitch is rather simple to fill in the space.

This stitch adds texture to a design and leaves a smooth satin-like appearance. We will use this for the middle of the rose.

Step 1

Bring the needle out through A and into B, the box outlined is an example of the space you would want to cover in a satin stitch.

Step 2

Bring the needle back and through to point C, which should be just beside point A. The next stitch would then be just beside point B, and so on.

Final image of a satin stitch, this should be used for the centre of the flower pattern.

Anna Laviniere is a Collections Management Trainee at London Museum, in partnership with Culture& and Create Jobs.