23 September 2024 — By Francis Grew

Smithfield Market: The iron legacy of Sir Horace Jones

Smithfield Market's architectural transformation highlights the engineering feats of Sir Horace Jones, showcasing the innovative use of ironwork and the market's unique place in London’s history of civil engineering.

The architects of Smithfield

“As I’ve walked round the General Market, appreciating the boldness of the ironwork and the fine detailing of the brick Vaults, I’ve often felt very close to the original designer, Sir Horace Jones,” says Paul Williams about the Smithfield Market building. He is the Principal Director at Stanton Williams, the lead architecture practice in a consortium working on the new London Museum at Smithfield.

“A superstructure…the size of Oxford Circus”

Paul Williams, Principal Director, Stanton Williams

As this iconic space is being re-imagined, it’s important to take cognizance of the vision of the original architects of the two magnificent buildings at its core. “Contrasting in style…the 1880s General Market exploits the structural capabilities of wrought iron, its 16 elegant Phoenix columns supporting a superstructure that covers a space the size of Oxford Circus. The 1960s Poultry Market stretches to the limit the plasticity of concrete, creating the largest clear spanning concrete domed roof in Europe,” he reflects.

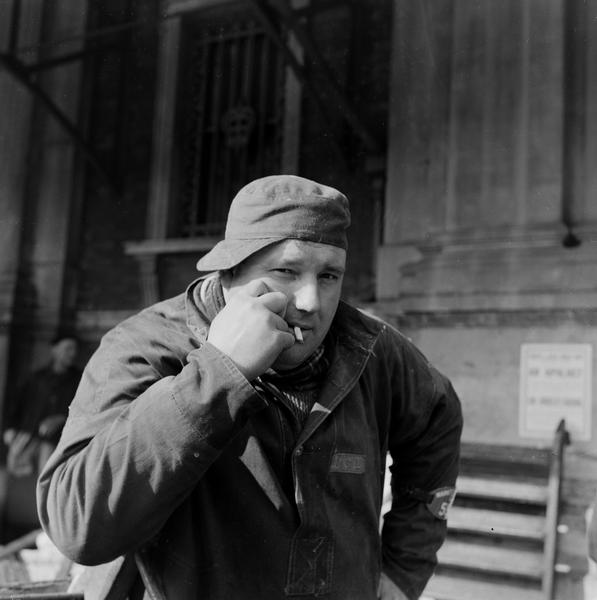

Sir Horace Jones: The visionary architect behind Smithfield Market

A portrait of the architect Sir Horace Jones (1819–1887) by Walter William Ouless.

“With respect to the Ironwork, a very large and special feature in this Structure, great care and very particular supervision has had to be given to this part of the works.”

So wrote Sir Horace Jones in February 1880, about the building that will house the museum’s Past Time and Our Time displays. Jones had been appointed Architect and Surveyor to the Corporation of London in 1864, and much of his extraordinarily heavy workload since had involved designing markets.

The Fish Market at Billingsgate had opened in 1877, and the retail shopping mall of Leadenhall would open in 1882. But one project outstripped them all in scale and complexity

The Smithfield development – which, besides meat, eventually included fish, fruit, vegetable and provisions trading, retail and wholesale – was a 25-year enterprise that wasn’t completed until several years after Jones’ death in 1887.

Engineering marvels of the market buildings

Jones’ first two Smithfield buildings, the Central Meat Market (1868) and the Poultry Market (not fully completed until 1878), had tested the engineering limits of the day. But the requirements of the new Fruit and Vegetable Market were even more demanding.

It had to be built on an artificial platform over a full basement, accommodate a steep slope, with a railway cutting through, and bordering the culverted River Fleet – all the while providing a vast, open trading floor instead of the narrower avenues of the meat-trading markets.

And that was just the interior.

“Internally, this is a structure of wood and glass, and of iron – huge quantities of it”

Externally, the new building would revitalise a run-down district by having parades of small shops on all four sides to turn this into a retail shopping centre as well.

From the outside, the brick facades and stone dressings of the retail shops look conventional, harmonious with many of the surrounding buildings at the time. But appearances are deceptive. Because underground was a set of magnificent brick vaults.

The significance of ironwork in the design

Internally, this is a structure of wood and glass, and of iron – huge quantities of it. Jones notes that by December 1880, about a year after the start of work, a total of 1,326 tons of ironwork had been delivered to the site, of which about three-quarters was already in position.

A proposed concept image of how the interior of the General Market will look, showcasing the original ironwork.

Deliveries would continue for the next year, with Jones often reporting that the iron foundry couldn’t keep up with the rapid timetable and the voracious demand for metal. “Considerable delay has arisen in the supply of…ironwork…and the Works have been greatly retarded and much extra labor and anxiety has been caused in consequence of this,” he scrawled in the margin at one point.

So, how was all this iron used and why was it so important?

The answer lies in the need to produce a large and uninterrupted space at both basement and ground-floor levels. This couldn’t be done with brick or stone vaults, or with relatively small cast-iron columns and girders as on the trading floor of the central Meat Market.

So here, Jones laid down an especially heavy-duty table of Portland cement concrete to support the “great weight” of the stanchions and special iron construction. These widely spaced columns carry the girders of the market floor and are mostly of composite wrought iron construction.

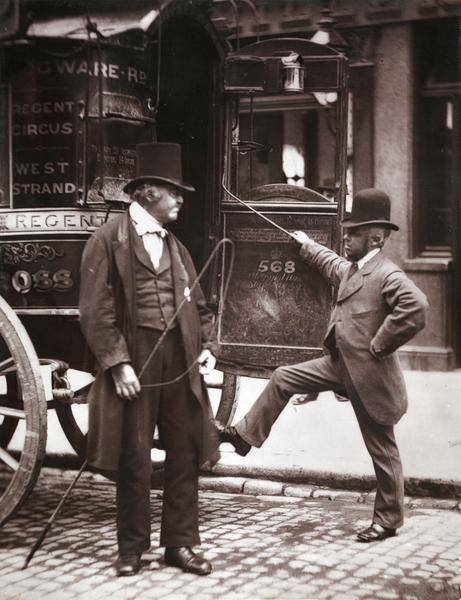

Phoenix columns: Supporting Smithfield’s roof

A close-up of one of the renowned Phoenix columns.

Above this, the entire interior roof structure is carried on just 16 gigantic Phoenix columns: an inner square of four beneath the dome, and an outer square of 12 to carry the plywood-trussed avenues of glazed and louvred windows. Each of these columns was made up of eight flanged sections, bolted and riveted together, and rolled out of wrought iron. That material was far superior to cast iron in terms of absorbing the lateral movement of a structure.

Quality control was essential, and we know samples from different batches were taken for testing to “Mr David Kirkcaldy of Southwark Street”, a well-known authority. Remarkably, these premises and the actual machine used for testing can still be visited today.

Much ink has been spilt in discussions on who manufactured the 16 giant columns. Some stress that this type of stanchion should have been protected by a patent from the Phoenix Iron Works of Pennsylvania. Others point to the superior quality of Continental ironwork at the time and suggest Belgium as a possible source.

Jones doesn’t comment specifically on the subject, arguably for fear of being found out for using an overseas supplier. But we should remember that composite wrought iron stanchions were not unknown in British buildings of the period.

Horace Jones’ love for ironwork

Unlike many contemporary architects – as opposed to engineers – Jones seems to have had a lifelong interest in the possibilities of ironwork to produce large spaces. Perhaps, it originated with his rebuilding of Caversham Park in Berkshire in 1850. A stately home, the owner was a Welsh iron magnate who insisted it be constructed around an iron frame.

As for the new Fruit and Vegetable Market, Jones talks of the “ironwork for Girders, Stanchions etc which is being rolled at Darlaston, Staffordshire”. He was probably referring to the Darlaston Steel and Iron Co.

“These might be one of the last major buildings in London constructed entirely of iron”

Jones’ market building holds a unique place in the history of civil engineering. This might be one of the last major buildings in London constructed entirely of iron as within a decade, wrought iron would be replaced by steel, with its much greater load-bearing potential.

But, in the meantime, we can only express our admiration and gratitude to Sir Horace Jones, this far-sighted and practical architect, who provided the cavernous spaces – as big as Oxford Circus, as Paul Williams puts it – that have the capacity for transformation into the new London Museum.

Francis Grew is Senior Curator of Archaeology (New Museum) at London Museum.

More about London Museum: The museum’s permanent galleries in the Victorian General Market are due to open in 2026. The 1960s’ Poultry Market, home to the museum’s temporary exhibitions, collection stores and learning centre, is scheduled to open in 2028.