11 April 2023 — By Nabil Al-Kinani

Ramadan in London: In search of ingredients from home

Jenan and her son Ayaan represent a significant Muslim population in London who travel across the city to get the ‘right’ ingredients for their home-cooked meals, especially during important occasions.

At the turn of the 21st century, the United Kingdom has become home to diverse and vibrant West Asian and North African communities, with London accommodating significant populations from countries such as Iraq, Iran, Egypt, Morocco, Algeria, Palestine and Syria. Despite facing challenges and discrimination, migrants have made and continue to make significant contributions to British society – think architect Zaha Hadid, footballer Mo Salah, and UK garage legend MC Mighty Moe of Heartless Crew.

Most people in West Asia and North Africa identify as Muslims, meaning they follow Islam – one of the largest religions in the world. Aside from the Islamic presence brought by migration in the 20th century, London has had long history of Muslim presence going back to traders and travellers in the 16th century onwards. Islam’s roots are in West Asia and the Arabian Peninsula, but its followers come from diverse ethnic and cultural backgrounds worldwide, and not all culturally identify with West Asian languages or customs. At the same time, being from West Asia does not necessarily mean one is Muslim: for instance, Yemenite Jews and Egyptian Copts are not Muslim.

The importance of Ramadan

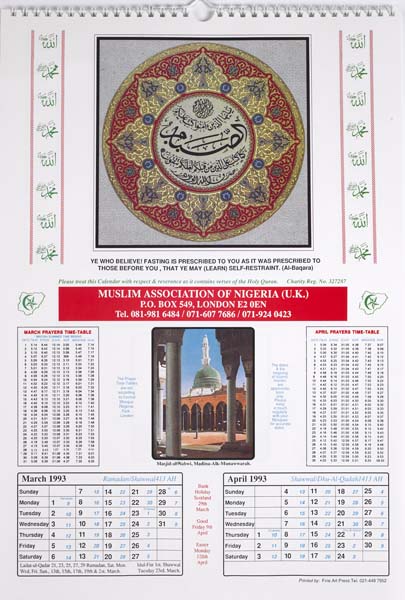

The month of Ramadan is a holy month for all Muslims and holds special significance as it is the month when the Holy Qur’an was revealed. Fasting during Ramadan is considered an act of worship and is observed with great devotion and reverence by Muslims around the world.

Ramadan represents one of the five pillars (‘tenets’) of the Islamic faith, where Muslims practise abstinence from food, drink and other physical needs from sunrise to sunset for a month – as an act of self-discipline and devotion to Allah (one of God’s names in the Islamic faith). In London, countless mosques and Islamic community centres provide support and resources for Muslims during the month of Ramadan. It is common practice to find Muslims coming together for communal meals, known as iftar or 'futoor' (Arabic for ‘breaking [of the] fast’), and engage in collective prayer, reflection and charity. Many community leaders organise events and activities that bring together members of the Muslim community. The end of Ramadan is marked by the celebration of Eid al-Fitr (Arabic for ‘festival of [the] breaking [of the] fast’).

During Ramadan, the diversity of London’s Muslim population is reflected in the variety of practices taking place in the city – Muslims from different ethnic and cultural backgrounds engage in a variety of activities unique to the cultural context of their countries of origin. For example, the traditional Cameroonian Ramadan practice involves leaving their doors open before iftar time, to invite those who may need to find somewhere to break their fast.

“Many [migrants] face the challenge of the adjusting to a new cultural context, and…search for traditional ingredients”

A sense of nostalgia

West Asian and North African food culture in London demonstrates the rich culinary traditions of countries such as Egypt, Lebanon, Iran, Syria and others in the region. From savoury wholesome meals and stews to flavourful sweets, pastries and baked goods – many establishments across London (irrespective of faith or beliefs) offer special Ramadan menus and iftar meals during the month – and extend their opening times to allow for customers to enjoy their meals from sunset to sunrise.

Many migrants find their initial experiences of Ramadan in London different to what they are accustomed to back home. Many face the challenge of the adjusting to a new cultural context, and many embark on a search for traditional ingredients they would have used in home cooking. These challenges have been particularly felt by refugees and asylum seekers, many of whom have fled West Asia, and Syria in particular, in recent years to seek humanitarian protection in the UK under international laws.

Generally, upon arrival to London, for instance, refugees are not given the option to choose where to live – and many are relocated in areas of the city with little or no connection to West Asian communities. As a result, many West Asian refugees face the practical, yet significant, challenge to find the necessary ingredients required to cook authentic home-cooked meals. Many people resort to using similar ingredients, but they often struggle to recreate the flavours and dishes they cherish the most. Ramadan intensifies the longing for familiar home-cooked meals, as for many it brings back memories of past and a sense of nostalgia.

‘From the (Middle) South East to North West’

In 2022, we tried to capture these nuances through the collecting project ‘From the Middle South East to North West’, as part of Curating London’s London Eats programme at the museum. The project aimed at telling the story of a Syrian family who fled the 2011 Syrian Civil War. It follows an elderly mother, Jenan* (meaning paradise/heaven) and her young adult son, Ayaan* (meaning gift of God) on their city journeys from their accommodation in Woolwich, south-east London to the north-west part of the city in search of ingredients to prepare authentic Syrian dishes for Eid al-Fitr.

Woolwich is host to a mix of retailers from various backgrounds – such as Chinese, West African, Caribbean, Turkish and East Asian – but lacks West Asian and North African retailers. As a result, Jenan and Ayaan often struggled to find the necessary ingredients to cook traditional Syrian meals, particularly during Ramadan when the longing for family celebration is heart-felt.

Their quest leads them to north-west London, an area with a high concentration of Syrian grocers and roasteries. This part of the city is home to several Syrian families who established businesses well before the 2011 Civil War to meet the needs of a growing London Syrian community. The location of these stores is often known through word-of-mouth among friends and relatives.

The museum’s collection documents Jenan and Ayaan’s travels to Willesden High Road, a ‘little Syria’ housing a range of grocers, restaurants, coffee shops, barbershops, nuts and confectionary shops, all sporting “Syrian” or “Al-Sham” on their store frontages. Al-Sham refers to the Levant, the region where Syria is located and which designates the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. The stores are stocked with an array of Levantine products, from shisha coal to baklava, tahini, herbs and spices, as well as dried nuts, fruits, cheese, butter and creams. During Ramadan, the roasteries on Willesden High Road adorn decorations and offer Syrian sweets, chocolates, biscuits, nuts and coffee.

“Eriq Sous is considered one of the most important drinks during Ramadan due to its nutritional value”

Coffee and Eriq Sous, alongside dates, are popular drinks found on virtually every Syrian dining table during Ramadan. (Courtesy: Nabil Al-Kinani)

Jenan and Ayaan’s travels yield various items that are now part of the museum’s collection, as well as the shopping trolley they used. These include a box of Eriq Sous (liquorice), a popular drink found on virtually every Syrian dining table during Ramadan. The drink is made by soaking wet root wrapped in a cloth in water and is served cold. It is considered one of the most important drinks during Ramadan due to its nutritional value.

Ma’amoul is another special item, explains Jenan, “a Syrian type of cookie offered to guests during important occasions, such as Eids and breaking fasts during Ramadan. It is a filled butter cookie made with semolina and flour. The filling is usually made of either dates or nuts such as walnuts and pistachios.”

Other yielded items include ground coffee, a staple in Syrian culture. Coffee is often served with added sugar as a sweet drink or plain as a bitter drink. “Drinking coffee in Syria is considered a ritual that can be enjoyed alone or shared with family and friends. It is an essential element of hospitality and is typically offered to all guests, whether for an occasion or a casual visit,” says Jenan.

The culmination of Jenan and Ayaan’s journey is a 'sufra', a communal dining experience where they, along with the rest of the family, can relish the taste of home, feasting on food they prepared with the authentic Syrian ingredients obtained on their journey from south-east to north-west London.

Nabil Al-Kinani is an urbanist, cultural producer and creative practitioner. This article is part of the London Eats project.

*Names changed to protect the identity of participants who are in the asylum process.