03 July 2023 — By Joana Vieira Varela

Of Victorian cravat pins & Cleopatra’s Needle

How did a chip off a 3,500-year-old Egyptian obelisk, braving an arduous journey across the seas, wind up encased in silver as a 19th-century fashionable Victorian cravat pin?

It’s the year of 1819. The 3,500-year-old Egyptian obelisk – popularly known as Cleopatra’s Needle – was presented to the British government by the then Sultan of Egypt and Sudan, Muhammad Ali Pasha. While the gift was accepted, and the over 200-tonne ancient structure was moved from Cairo to Alexandria, where it sat for 58 years, awaiting transport to England.

In 1877, Cleopatra’s Needle finally started its voyage to London, and that is where our journey starts as well. While looking through our collections, we found an interesting piece – a cravat pin. A simple fashion accessory at first glance, this item has something only a keen observer would notice – an inscription on its side that says “Chip of Cleopatra’s Obelisk, 1878”.

“Could it be that the embedded stone is a chip from the Cleopatra’s Needle, now at Victoria Embankment?”

The obelisk – gifted to Britain in appreciation of Admiral Sir Horatio Nelson’s victory against the French during the Battle of the Nile in 1798 and Sir Ralph Abercromby’s victory at the Battle of Alexandria in 1801 – was brought in from Egypt to London in 1877, in a specially encased capsule that was then hailed as a feat of engineering.

Sir William James Erasmus Wilson, an anatomist, dermatologist and philanthropist, sponsored its transportation to London. Successful international engineering contractor John Dixon was appointed the chief engineer in charge of the transport project, assisted by his brother Waynman Dixon, also a well-known engineer, who was tasked with building the transport cylinder for the obelisk.

How Cleopatra’s Needle got to London – in watercolours

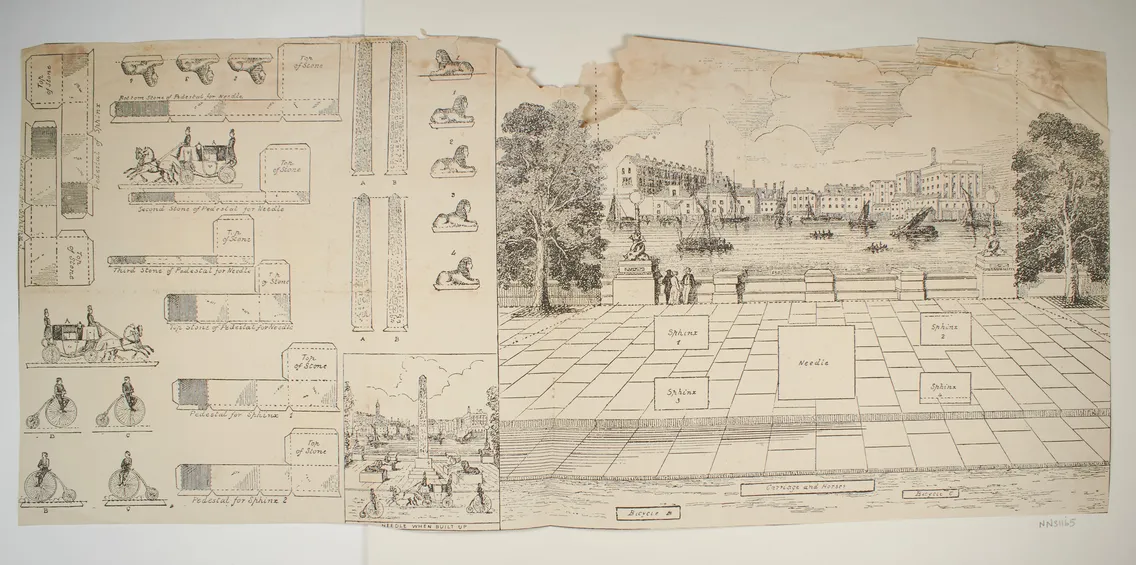

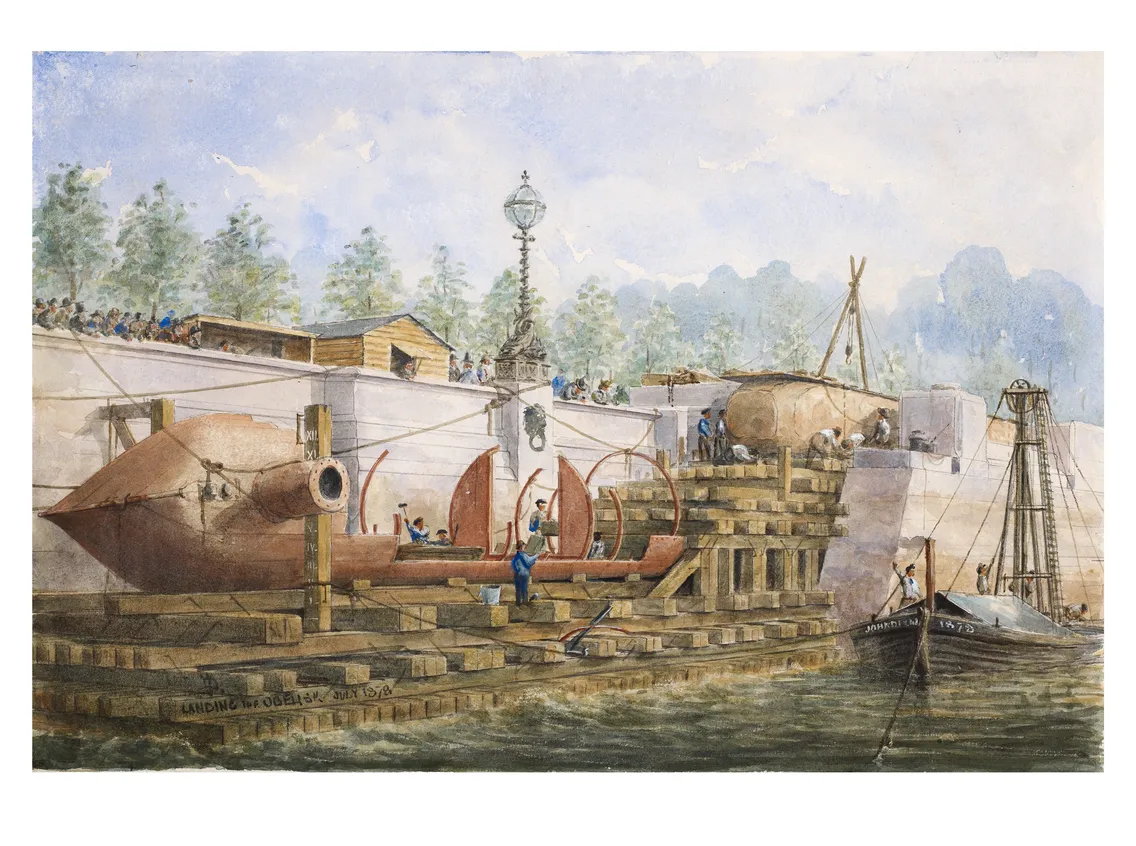

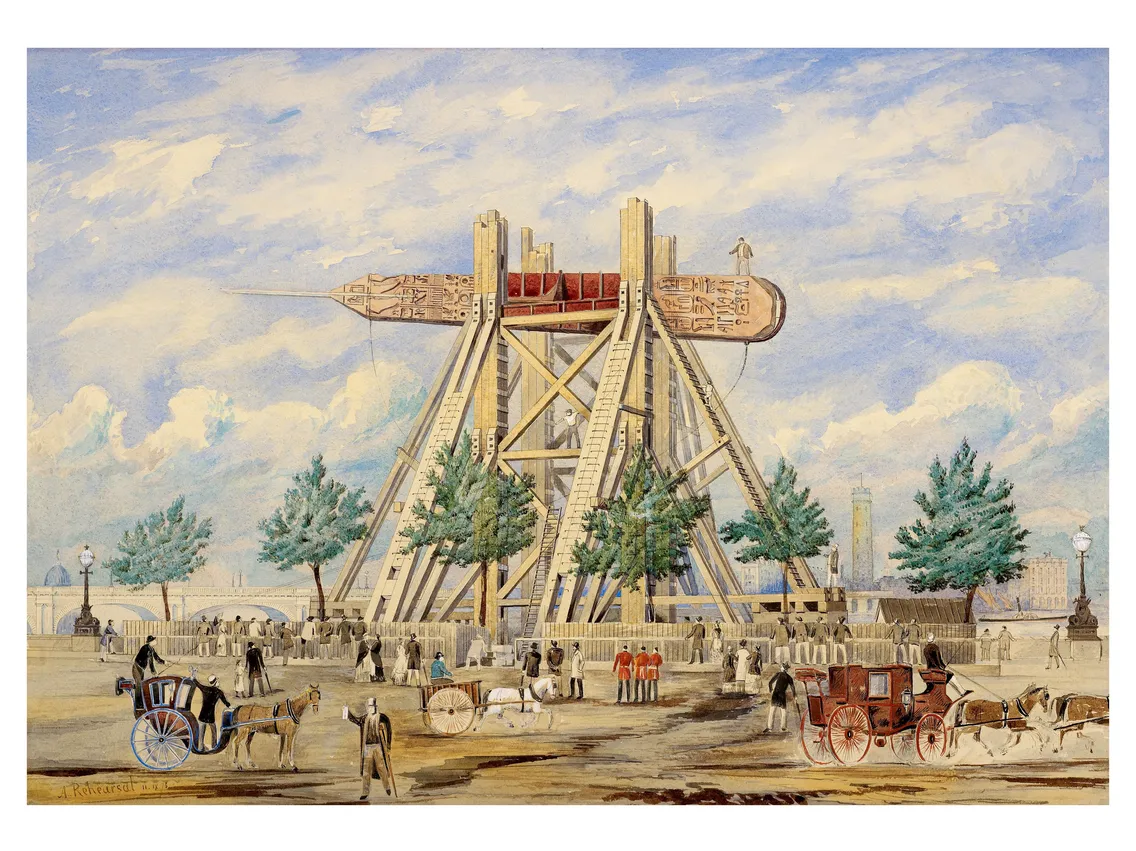

A further dive into the museum’s collection, and we found that John Dixon, who was also a photographer and painter, had painted a series of beautiful watercolours between 1877 and 1878 depicting how he had envisioned the transport of the monument. Photographs and prints of these watercolours are in the museum’s collection.

Interestingly, unlike the depiction in Dixon’s watercolours, we know that the obelisk was transported from Alexandria encased in an iron cylinder, which was then rolled using levers and chains down a track into the sea. It was fitted with a deckhouse, mast, rudder and steering gear and manned by a crew of Maltese sailors. This craft was named ‘Cleopatra’ and was to be towed to Britain by the steamship ‘Olga’. Braving a storm and after the loss of six men, the needle made its way to English shores.

Its proposed location was in St Stephens Green, as you can see in one of the watercolours, but once news reached Metropolitan District Railway that such a heavy monument might be erected directly above their rail line, concerns were raised. It was “feared the vibrations set up by trains would one day encourage the needle to drop into the tunnel”, as reported in R.A. Hayward’s Cleopatra's Needles (1978).

“Not known to many, the Victorians planted a time capsule underneath Cleopatra's needle”

The obelisk’s location was then moved to Victoria Embankment, where it was finally placed on 12 September 1878, and where it continues to stand tall today, guarded by two sphinxes designed by the renowned British architect George John Vulliamy. Not known to many, the Victorians also planted a time capsule underneath the needle.

Erecting Cleopatra’s Needle in London

To lift the obelisk into position, Dixon’s team of engineers created an iron girdle, with pivots at its centre, laying the needle horizontally. To elevate it, a massive wooden framework was built astride the obelisk, it was raised with jacks and then lifted the monument to its vertical position, where it was secured on its ornate base, also designed by Vulliamy.

With the help of our Librarian Lluis Tembleque Teres, we came across an 1878 manuscript by well-known architect William Beck in our library’s special collection, which details the raising of the obelisk. In this work, he mentions a Telegraph article in which Queen Victoria congratulated Dixon and Prof. Wilson “on the successful termination of their enterprise”.

Now that Cleopatra’s Needle is up in its place, we’re back to our beautiful cravat pin

A chip off the old block

Did a piece fall off, or was it chipped off? We’re not sure. We do know that our pin belonged to author-historian-curator Henry Walter Fincham (1860–1952). Maybe he got it as a gift from one of the engineers? Or, maybe, he just found the chip and fashioned it into a pin? In early 2023, two cufflinks also adorning chips from the obelisk were auctioned in Birmingham, indicating that these trinkets were part of a Victorian trend of “collecting items of historical and cultural value”.

As the first curator of the Museum of the Order of St John, Fincham was an antiquarian, amongst other things, and he was described has having had a keen eye for valuable items. He collected small fragments of objects, which lead us to believe that he might have acquired the shard and had it embedded in the cravat pin. Or, perhaps, he purchased it of someone who worked in the transport of the obelisk? We can wonder. The wonderful pin was donated to the museum by his son, William Henry Angel Fincham, in 1977.

Worn vertically to secure neckwear, with a decorated head, this kind of jewellery was a vehicle for novelties of all kinds, such as this piece of Cleopatra’s Needle.

The pink and grey granite stands out encased in the silver collet, catching the observer’s eye. Could Fincham have visited its twin in New York, or cousins in Paris and Luxor? Did he share tales of how the one sitting on the Thames’ bank arrived there? Perhaps, he could have told the story of how he came to acquire a small piece representative of such an iconic feat of engineering.

An item close to one’s heart, and kept close to eye level, this cravat pin was certainly a conversation starter.

Joana Vieira Varela is Project Assistant (Archaeology) at London Museum.

Do you have any commemorative items at home? Let us know and share your story on social media tagging @wearelondonmuseum