02 August 2024 — By Wendy Shearer

Notting Hill Carnival: Memories, roots & rhythms

A personal journey through London's iconic Notting Hill Carnival, exploring its Caribbean roots, cultural significance and evolution over decades.

My parents are Guyanese and I grew up in the 1970s and 80s in south London, where there was and still is a large Caribbean community. My childhood memories are rooted in Caribbean-British culture, with visits to Surrey Street and Brixton market with my Nan to buy her provisions of sweet potatoes, cassava and fish; attending Saturday Supplementary School for children (not exclusively) of African and Caribbean heritage; enjoying youth club at my local Samuel Coleridge Taylor Centre, staying up late at family house parties and dancing through the streets during Notting Hill Carnival.

“I soaked up the feeling of freedom as everyone came together, smiling, dancing and watching the parade”

Caribbean roots in south London

Before I hit my teenage years, we always went to the carnival on ‘children’s day’, which is traditionally held on a Sunday. I loved the atmosphere – an electric mix of musical mayhem and vibrant colours wrapped up in the tantalising smells of Caribbean food. We’d pick a float to dance behind along Ladbroke Grove, and I longed to be one of the children dressed up in the parade with their large costumes – colourful feathers, beads, sequins and headpieces.

My dad explained to me: “these traditional costumes with African and Indian designs are part of the carnival story. This is how we remember our ancestors who celebrated their freedom during colonial times in the Caribbean.”

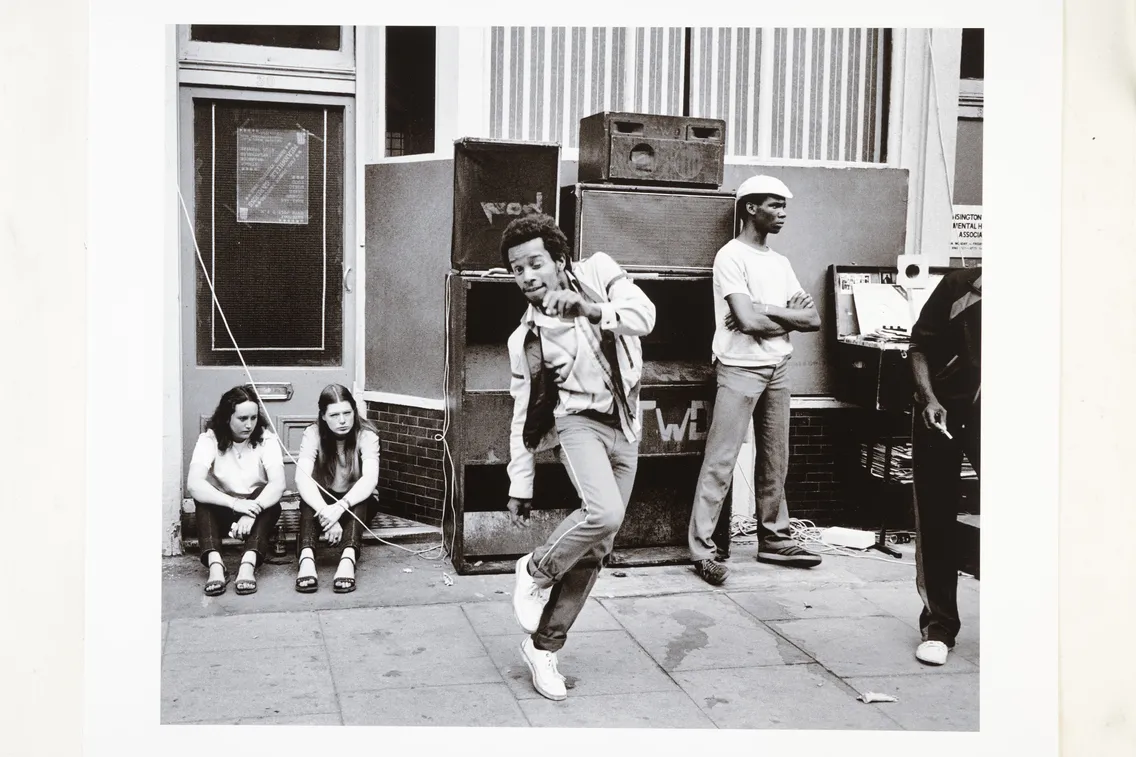

I soaked up the feeling of freedom as everyone came together, smiling, dancing and watching the parade. Whenever we were tired of walking, we’d always head to one of the music sound systems, which is the heart and soul of the carnival. DJs play all kinds of music from Reggae to Samba. My parents always took us to the Soca Sound System.

Soca originated in Trinidad and Tobago and is very popular in Guyana, so this is the sound of my youth. I finally got my wish of being part of the parade when I turned 14. I invited a couple of school friends and we danced behind a steel pan float. My friends were of Scottish and Indian heritage and had never been to Notting Hill Carnival before. We wore carefully crafted costumes of red, white and blue to represent an angel, devil and queen – revelling in how united we all were.

Adult carnival: Joy and tension

I’ll never forget the first time I attended the ‘adults day’ at Notting Hill Carnival. It was 1989 and I was 16. It was a significant time for me, attempting to throw off the shackles of childhood and assert my independence. My parents were planning to head to the soca system as we always did, but I headed off with my friends to hear rare groove and reggae. Once again, the atmosphere was high energy with Mas dancers in incredible costumes leading the way, but this time it felt extremely crowded and we sensed tension in the air.

“The mood had changed from one of joy, liberation and freedom to resistance and protest”

We danced alongside the steel pan float with its two tiers of musicians. Everyone was blowing their whistles in between the beats. In previous years, I was aware of a few police officers who blended into the background or danced alongside us, but that year there was a wall of white shirts and what would later be described as an unprecedented level of policing.

Certain streets were blocked off for safety to avoid a bottleneck where floats could not get through. This seemed like sensible guidance, but while partying it aggravated many people.

The words “enough is enough” floated through the air as revellers tried to get past barriers and head down streets. Towards the end of the evening, I remember feeling a massive surge of people and seeing bottles flying at the police. The mood had changed from one of joy, liberation and freedom to resistance and protest. Ironically, the carnival was born as a response to ease tensions after the 1950s race riots and a desire to unite communities who lived alongside each other, but did not necessarily mix.

In 1959, Claudia Jones, a Trinidadian human rights activist organised the first Caribbean carnival, which was broadcast by BBC and held inside St Pancras Town Hall before it eventually grew to become the street festival we now know as Notting Hill Carnival.

The 1997 Touch Guide to Notting Hill Carnival.

The carnival's evolution through decades

When I attended the carnival in the 90s as a young adult, I understood even more how important it was to the community. I was acutely aware of how little representation there was of Black history and culture in our school curriculum, in supermarkets and bookshops. But at Notting Hill Carnival, there was an opportunity for people of a variety of ethnicities to mingle, celebrate and represent.

The mid-1990s were the start of my clubbing years and my favourite DJs were Richie P and Mike Anthony, who started Rampage, mixing all forms of urban music. Mike lived in Notting Hill and I was ecstatic when he and his friends brought the Rampage sound system to Colville Terrace. Over the years, they became the biggest sound system at the carnival with amazing artists performing on their stage. The atmosphere was now like a free concert for the community with artists such as Shaggy, Ms Dynamite, Dizzy Rascal and Stormzy to name just a few, rocking up to take control of the mic.

During the mid-2000s, I took a break from the carnival as motherhood took over and attended the Guyanese folk festival, with lots of traditional food, soca music, artists and entertainment.

A constant community tradition

Notting Hill Carnival splashed onto our London streets in 1966, and has remained a constant Caribbean community tradition, which now attracts around 2 million people, over 50,000 performers and 30 sound systems over the August Bank Holiday weekend. Even during the Covid-19 lockdown, they found a way to bring the celebration into our homes by performing online. I remember my whole family having a day-long dance-a-thon in our living room.

For the next carnival, we might attend the early morning ‘J’Ouvert’ (derived from the French words ‘jour ouvert’, meaning ‘opening of the day’). It’s a traditional way to start the carnival just before sunrise and get messy with colourful paints, powder and, sometimes, chocolate to represent the mud and oil tradition in the Caribbean. It’s a beautiful way to welcome the day and embrace traditions that are rooted in remembrance.

Wendy Shearer is a London-based professional storyteller, writer and mother of two who loves to dance.

She's curated a list of books (all available through our online shop) highlighting stories of Black British people that deserve to be shared, celebrated and remembered.