02 February 2019 — By Alwyn Collinson

Mapping London’s LGBTQ+ history in our collection

We take a look through our collection for signs and symbols of the centuries-long struggle by LGBTQ+ Londoners for acceptance, recognition and equal rights.

For most of London's history, people who practise same-sex love or transgress traditional gender identities have lived hidden lives, for fear of punishment and censure. When they appear in the historical record, it is usually because they are being prosecuted or vilified. From 1533 in England, homosexual activities between men were a crime punishable by death. Despite the great personal risk they faced, men who had sex with men still created a vibrant subculture in London. In the 18th and 19th centuries, certain London pubs and coffeehouses became popular gay meeting places, known as ‘molly houses’. We know about these activities from the writings of contemporary moralists, who denounced the growth of ‘Almighty sodomy’.

The 18th century book Plain Reasons for the Growth of Sodomy in England attributed a supposed increase in homosexuality to men’s dress. From the 19th century, male attire was dark and plain. It was not until the 1960s that gay men’s flamboyant dress styles influenced mainstream fashion, making it more colourful and adventurous. More evidence of historical homosexuality in our collections comes from a grimmer source: records of the prosecutions, and sometimes executions, of men who had sex with men.

Who was Samuel Drybutter, aka ‘Ganymede’?

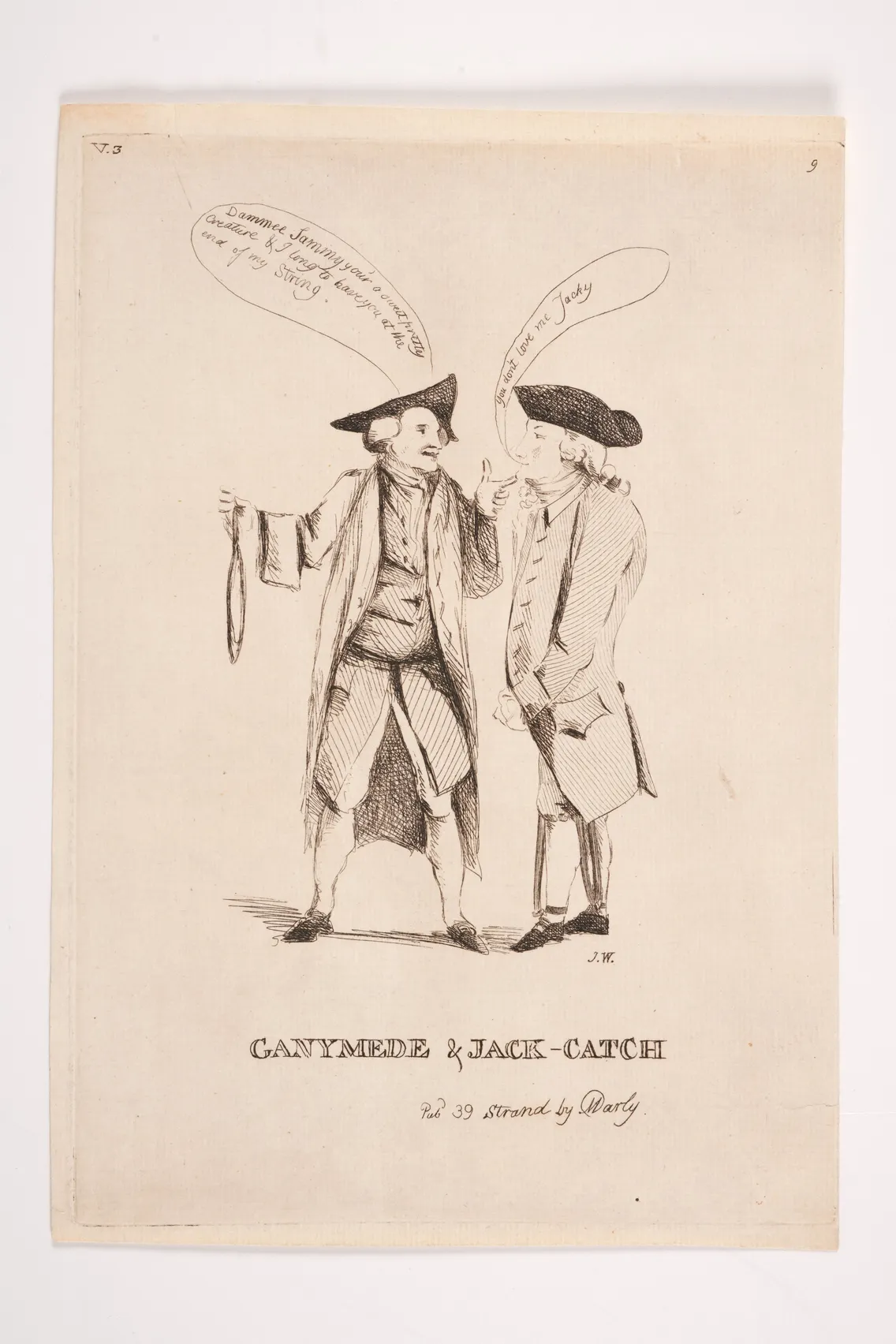

A 1776 print shows Samuel Drybutter, a bookseller in Westminster Hall, who was a public figure in 18th-century London, famous for his flamboyant dress and supposed homosexuality. Drybutter was a prominent ‘Macaroni’, men who dressed in extravagant fashion and whose behaviour was stereotyped as affected and unmanly.

Drybutter was arrested on many times for attempted sodomy but managed to escape prosecution. He was publicly ridiculed and suffered various physical attacks. Satirists nicknamed him ‘Ganymede’, after a shepherd boy who was the lover of the god Zeus in Greek mythology.

In the print, the figure speaking to Drybutter is Jack Catch, a nickname given to English executioners. Jack the hangman, holding a noose, says, “Dammee Sammy you’r a sweet pretty creature & I long to have you at the end of my string.” Drybutter, shackled in leg irons, replies, “You don't love me Jacky.” Despite the comical tone, it’s a grim reminder of the constant threat of violence that hung over those who stepped outside the norms of sexuality and gender in past London.

Pinning symbolisms of Pride

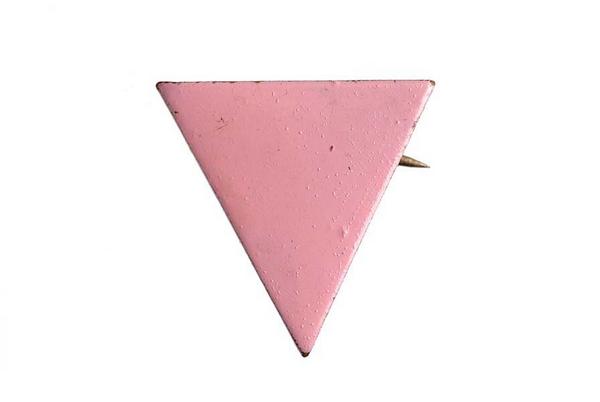

The museum’s collection has a number of badges celebrating Pride and gay activism created during the 1970s and 80s. At the time, wearing them on the streets was a powerful and dangerous political statement, sometimes met with abuse or violence. The pink triangle badges are a reference to the cloth badges that gay prisoners were forced to wear in Nazi concentration camps. Gay victims of Nazism were not freed by the Allied occupiers of Germany in 1945, but were forced to serve out remaining prison sentences for their ‘crimes’.

Other symbolisms on the badges include safety pins in the mid-1980s – symbols of the punk movement that emerged in London and attracted many LGBTQ people with its resistance to oppressive authority. ‘Scrap the Section!’ pins referred to Section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988, under which local authorities were prohibited by law from “promoting homosexuality by teaching or by publishing material”, effectively banning help for LGBT people from schools, libraries, and community groups.

It was the first anti-gay British law passed since 1885. Following a mass campaign, the section was finally repealed on 18 November 2003.

UK’s oldest LGBTQ+ bookshop

'Defend Gay's The Word' lapel badge, 1984–1985. This badge was worn by a supporter of the campaign to defend the bookshop.

Gay’s the Word is a bookshop located on 66 Marchmont Street in Bloomsbury. Founded in 1979, it’s the only bookshop in Britain that specialises in gay and lesbian literature. In 1984, Customs and Excise officers raided Gay’s the Word as part of ‘Operation Tiger’. They seized all imported titles on the grounds that they were obscene. The case went to the European Court in 1985 and the charges were eventually dropped. This badge in our collection was worn by a supporter of the campaign to defend the bookshop.

Talking Pride through jewellery

A silver labrys earring, 1999. Lesbian and feminist groups adopted the symbol of the labrys in the 1970s.

Many items relating to LGBTQ+ history in the museum’s collection are much less visible. They reflect the difficulty of living in a London where being gay could cause you to be sacked from a job, publicly shamed, or even arrested.

One such piece is a silver earring in the shape of a double-headed axe called a ‘labrys’. The labrys is believed to have been used as a tool by a number of ancient civilizations for the dual purpose of fighting and harvesting, and is linked to the Amazons, a mythical tribe of female warriors. Lesbian and feminist groups adopted the symbol of the labrys in the 1970s. Wearing jewellery like this is one way for lesbians to indicate their sexuality.

Gender non-conformity through the centuries

Some Londoners from history have broken out of strict gender identities, either through their clothing, or by living a secret life in another gender. An 1804 print shows Theodora Grahn, a woman from Berlin who dressed in male clothing while working in London. Theodora, who styled themselves ‘Doctor John de Verdion’, worked as bookseller, secretary and a teacher of languages in Regency London. They appear to have become a well-known, if much-mocked, figure. Their true gender known, but tactfully ignored. Whether they were transsexual, or simply determined to live a life unavailable to an independent woman in 19th century London, is uncertain.

Another evidence from our collection is from the 20th century. A ‘Mudman’ skirt, produced by Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren in 1983 was worn by the male clothes designer Dane Goulding. He said, “I really owe a huge debt to Miss/Mrs Westwood… I honestly never bought her clothes to look cute, I always felt as though I was commenting on a world I was really unhappy with.”

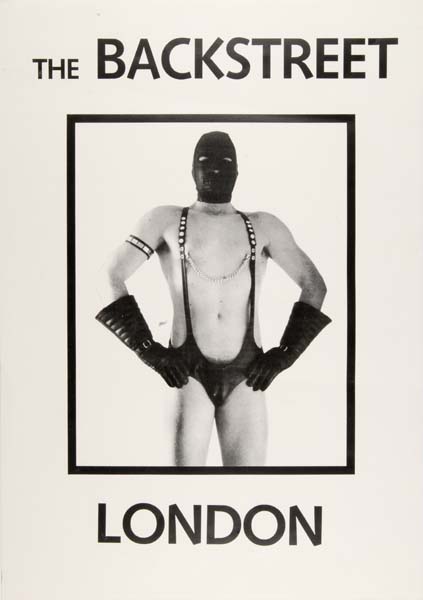

Legal equality and social recognition for LGBTQ+ Londoners has been gradually won over the last 50 years, and we continue to collect material that reflects this progress. In 2017, London Museum acquired clothes from the wardrobe of Francis Golding, award-winning London architect and fashion icon. And in 2022, we acquired 28 items from The Backstreet club, London’s longest-running, men-only leather bar, which closed in July of the same year.

Alwyn Collinson is Digital Editor at London Museum.