14 January 2025 — By Suyin Haynes

Lunar New Year in London: Celebration, change & Chinatown

From Chinatown feasts to family hotpot gatherings across generations, a mixed-heritage journalist and her mother share how Chinese Malaysian traditions blend with British culture for Lunar New Year celebrations in London.

It’s late January in London, and the cold, damp air is punctuated by hundreds of suspended red lanterns that sway to the beat of rhythmic drumming. Crowds of people surge through the streets of Chinatown, hoping to catch a glimpse of the mystical lion.

In the shop doorways, red packets known as ‘ang pao’ hang alongside whole heads of Chinese lettuce, waiting to be gobbled up by the hungry creature to symbolise good luck and prosperity for the year ahead.

“For many peoples and cultures across East and Southeast Asia, it’s the most important festival of the year”

Queues line the streets waiting for dim sum, and trolley carts of vegetables rattle on their way to replenish depleted supermarket shelves. We try to go early to ensure a good table near the window on the first floor at our usual restaurant, New Loon Fung (every family has their favourite restaurant in Chinatown, and we’re no exception).

It’s a typical scene in London during Lunar New Year, which begins on the first day of the first lunar month in the calendar and ends on the 15th day. For many peoples and cultures across East and Southeast Asia (ESEA), it’s the most important festival of the year and is known by many different names, including Seollal in Korean, Tết in Vietnamese and Spring Festival.

Signs and symbols of the Lunar New Year at Camden Chinese Community Centre.

The evolution of a pan-Asian celebration

Growing up, I’d always heard it referred to as Chinese New Year. My relatives in Malaysia still use this phrase while planning their meals together in our family WhatsApp chat. Yet, the term Lunar New Year has now become more widely used, reflecting the festival’s rich diversity across ESEA communities worldwide.

These red pouches and money envelopes given during Lunar New Year symbolise luck and prosperity.

Here in London, for example, Chinatown and the symbols or rituals described above may not factor in some families’ celebrations at all. For others, it may be a focal point of gathering during the fortnight of festivities.

As the daughter of one Chinese Malaysian parent and one white British parent, and as a born-and-raised south Londoner, I’ve seen my own relationship with the festival transform. My mother, who came here to train as a nurse in 1974, left behind some of her cherished traditions. One such tradition is a 'reunion dinner’ hot pot, held on the eve before the first day – so called because it marks the homecoming of relatives back to the family home.

She tells me that Lunar New Year celebrations didn’t feature much in her personal journey of building a life here in the UK during the 1970s and 1980s, although she and her fellow Malaysian classmates often made an effort to eat a meal together to mark the occasion.

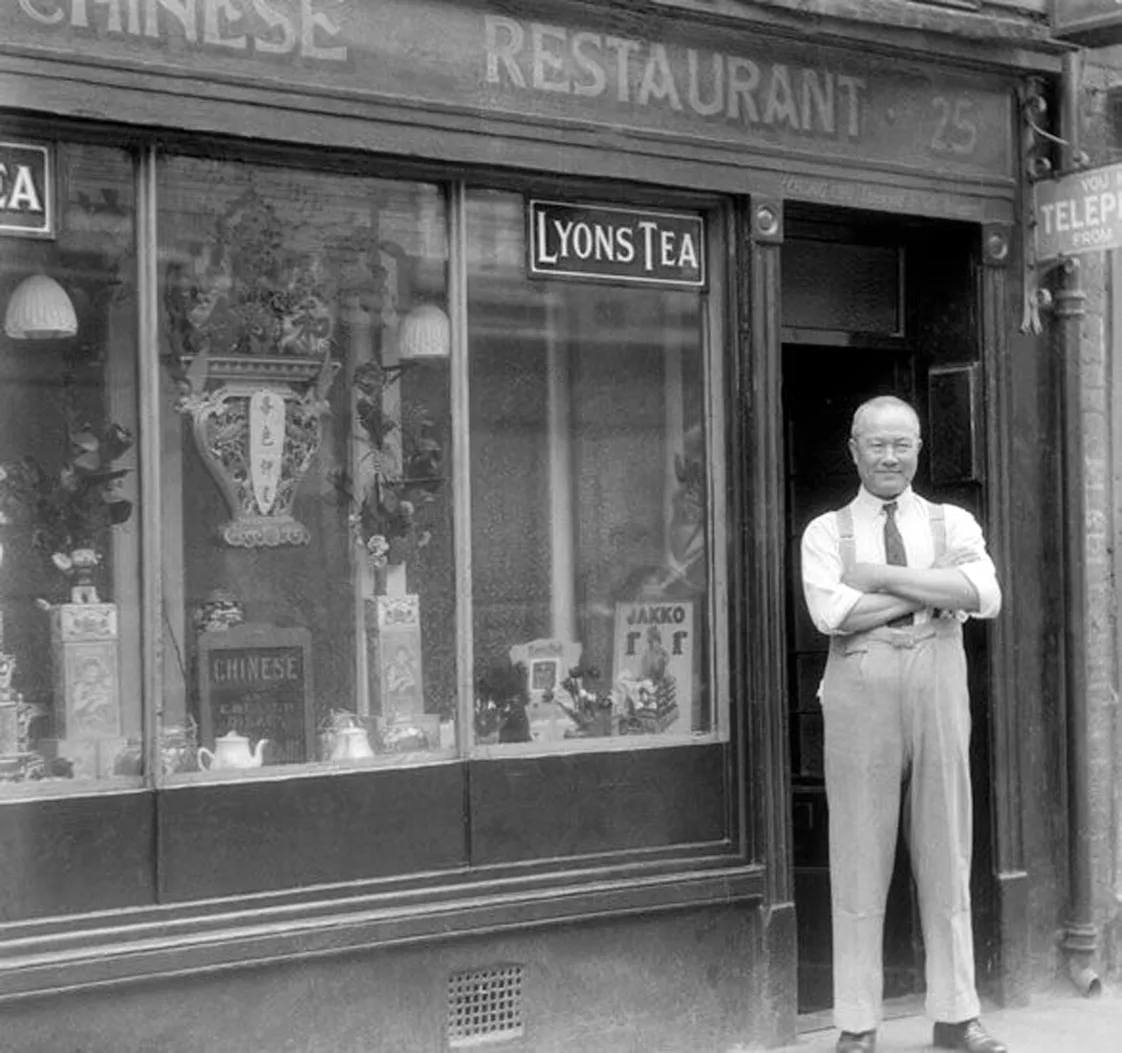

A history of community, celebration and Chinatown

Yet, the years that marked my mother’s migration to the UK also marked the first public, organised festival celebrations in Chinatown, mainly in Gerrard Street and parts of Soho. Here, a cluster of businesses run by migrant entrepreneurs, largely hailing from Hong Kong island and the New Territories, had blossomed since the early 1950s.

“There was a really strong sense of community in the early days of Chinatown”

Dr Xiao Ma, scholar

“There was a really strong sense of community in the early days of Chinatown,” says scholar Dr Xiao Ma, whose work focuses on culture and heritage in London’s Chinatown. Initially celebrated privately among the business community, Lunar New Year has now become a time for more people, including migrant communities, coming to Chinatown to experience the atmosphere and celebrations.

In 1985, the launch of official Chinese New Year Celebrations in London, as organised by the London Chinatown Chinese Association, coincided with the area being officially named ‘Chinatown’ by Westminster City Council. This reflected the importance of the area to the diaspora entrepreneurs and communities. In 2002, the celebrations expanded to include Trafalgar Square for the first time, complete with a stage, international performances and political VIPs in attendance.

Today, the celebration attracts thousands of members of the Chinese diaspora, the broader ESEA diaspora groups, tourists and Londoners alike.

Pride, identity and cultural connection

As Xiao has observed over 12 years of living in London, such high-profile, visible celebrations hold different meanings for different people. For younger generations with Chinese or ESEA heritage, Lunar New Year can be a source of pride through visibility, she says.

“People are exploring their identity as Londoners...living in a multicultural city in a celebratory way”

“It’s not always easy to grow up as a minority, and sometimes, people may associate their cultural practices with shame. So, to see how Lunar New Year is celebrated at this kind of scale does create a sense of pride,” she reflects. Xiao also points to its wider significance beyond diaspora communities too. “You feel people are exploring their identity as Londoners. I met so many people who are local Soho residents, exploring what it is like to live in a multicultural city in a celebratory way.”

Dragon dance during Lunar New Year celebrations at London Museum Docklands.

Yet, alongside the celebration comes complexity. Xiao and I reminisce about our experiences of walking together representing the charity China Exchange in the Lunar New Year parade through Chinatown in 2023. It was the first year that in-person celebrations resumed after two years of virtual events due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Chinatown as a site itself was deeply affected by the pandemic in different ways, including anti-East Asian racism and discrimination, and the financial impacts of lockdown.

Personal reflections on cultural heritage

That sense of holding celebration and complexity together resonates with me deeply when it comes to thinking about my own relationship with the festival. Only in recent years have I grown to actively consider and create what it means to me, rather than feel pressure to do the rituals and customs perfectly or worry that I’m not ‘doing’ it right at all.

I think this has come from a sense of what Xiao mentions earlier: from having more pride in my Chinese Malaysian heritage and feeling more comfortable celebrating that openly with my mother.

We have run dumpling virtual cook-alongs to fundraise for organisations working with ESEA communities, been to thoughtful Lunar New Year events run by both grassroots community groups and cultural institutions in London, and, of course, continued going to New Loon Fung for our customary dim sum.

We’ve also worked to recreate our version of the ‘reunion dinner’ with friends, journeying to Wing Yip in Croydon and carefully selecting our favourite brands of tofu skin, cuts of meat and three types of mushrooms for cooking collectively in the hotpot.

And I have also come to think of it as a time of reflection and renewal – with this year being the Year of the Wood Snake, I will be thinking about how I’d like to bring its qualities to my year ahead.

Linda Haynes preparing for a hot pot with friends.

For Xiao, who grew up in Gansu Province in northwestern China, Lunar New Year back home has traditionally been about family reunion, rituals and ancestor worship. “We will always leave a bowl with food for our departed family members in a symbolic way,” she says.

This year will mark the first time that her parents will join her in London for this Lunar New Year. “I think I will take them to the parade and they will be surprised to see it,” she says. “They will see the busy atmosphere, the traditional celebrations, and very interesting slices of history from the past.”

Suyin Haynes is a freelance journalist, media consultant and lecturer in journalism at City, University of London. She covers identity, culture and underrepresented communities.