06 October 2022 — By Curatorial

London’s dark public execution history in 5 objects

From an 18th century gibbet to a 300-year-old bed sheet embroidered with human hair, we delve into what these five objects say about public executions in London over 700 years.

This page contains content some people may consider sensitive, or find offensive or disturbing. Understand more about how we manage sensitive content.

London was once known as the City of Gallows. Tens of thousands of people were executed here, from the first recorded execution at Tyburn in 1196 to the last public execution at Newgate in 1868. London’s courts condemned more people to die than those in the rest of the country.

These visible demonstrations of state power and violence attracted vast numbers of spectators. They became a key feature of London and part of the collective experience of living in London during this period. By the end of the 18th century, over 220 crimes – from murder to sodomy and theft – were punishable by death under what was known as the ‘Bloody Code’.

A wrought iron gibbet cage used to hold the corpse of an executed felon.

The following five evocative objects from our collection that represent key aspects of London’s execution history, which were on display during our 2022–2023 exhibition, Executions. Along with the personal story, these objects also reveal the wider impact of public executions on London and its citizens.

Of all the dreadful ways that public state death was meted out, some methods were more horrific than others. Take, for instance, the punishment for treason, dating back to the 12th century: “Traitors were ‘drawn’ or dragged from prison to the execution site, hanged until they were nearly dead, then castrated, disembowelled, beheaded and cut into quarters,” as explained in the book Executions: 700 years of public executions in London.

The practice continued into the 19th century, but by then traitors were hanged until dead before decapitation. Boiling and burning were some other methods.

City of gibbets

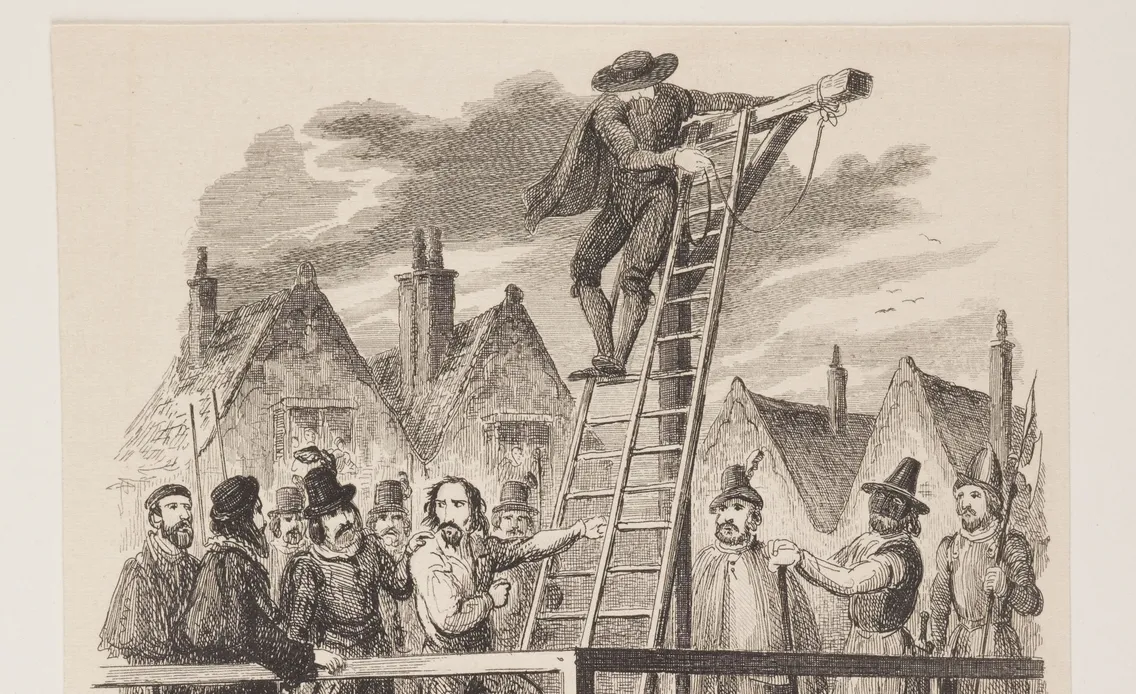

A satirical print by William Hogarth shows Tom Idle being taunted by a sailor pointing to a gibbet.

‘Hanging in chains’, or gibbeting, was an additional harsh punishment used for crimes such as highway robbery, piracy, smuggling, robbing the mail, and murder. The executed body would be cut from the gallows and put in an iron cage and hung from a gibbet, a vertical pole with a horizontal arm from which the cage would be suspended – often for many years.

Gibbets were usually located on roads leading into London, on open ground such as Wimbledon Common or along the River Thames so no one entering the capital could escape witnessing the fatal consequences of crime. Similar to public executions, gibbets attracted huge crowds, particularly on Sundays when food and drink stalls were set up around the sites, to take advantage of the money-making opportunity.

Notorious murderer William Smith’s gibbet on Finchley Common was visited by 40,000 people on the Sunday after his execution in 1782.

Most gibbets were bespoke, and individual bodies were measured by the blacksmith who made the cage to ensure a good fit. The gibbet cage in the museum’s collection is unusual in that it was adjustable and, therefore, re-usable. Shockingly the practice of gibbeting only ended in 1834.

A ceremonial axe as a symbol of state power

The axe made for the execution of the Cato Street conspirators in 1820 is a powerful warning to those contemplating rebellion. The conspiracy was an attempt by radicals to overthrow the government by assassinating Prime Minister Lord Liverpool and the cabinet. Betrayed by a spy, the radicals were charged with conspiracy to subvert the constitution and levy war. Five of the revolutionaries Arthur Thistlewood, Richard Tidd, James Ings, William Davidson and John Brunt were sentenced to the traditional traitor’s punishment of drawing, hanging and quartering.

This symbolic axe was not used to behead the men, but placed on the scaffold near the wooden block on which the men’s heads were severed by a masked man with a surgical knife, after they died on the gallows.

Public executions accounted for a thriving economy

An execution broadside 'The Particulars of those Ordered for Execution' printed with an account of the crime, trial and execution, 1824.

“A 'good murder' could sell up to 250,000 copies”

High-profile public executions were often attended by crowds of tens of thousands, and had a significant impact on London’s economy. The long wait at the gallows proved highly lucrative for street sellers of 'gallows literature' and refreshments. Long before national newspapers, accounts of crimes and executions were published in cheap pamphlets and broadsides. These were sold by patterers at the site of execution and, in the following days, throughout the country. A 'good murder' could sell up to 250,000 copies!

The hire of window views and grandstand seating to wealthier spectators benefited both individual householders and the authorities. The execution of the banker Henry Fauntleroy, who was condemned to death for appropriating funds by forging trustees’ signatures, was said to have been attended by a crowd of 100,000. Pickpockets profited from the crush, while the boisterous atmosphere benefited taverns, alehouses and mobile pie sellers. Critics argued that public execution days disrupted London’s economy and encouraged idleness and the loss of working hours.

King Charles I execution vest, the investigation continues

A miniature portrait of King Charles I, the likes of which were sold as memorial jewels at the time.

For contentious public executions, such as the beheading of King Charles I, crowds were highly controlled to prevent disruption to the proceedings. The king’s execution has captured public imagination for centuries. For some he was a martyr, and there is an eyewitness account claiming that, at the moment the King was beheaded, “there was such a groan by the thousands then present as I never heard before and desire I may never hear again”.

A silk vest that was allegedly worn by King Charles I during his execution.

The museum has several garments reputedly worn or carried by Charles at his execution. While there are conflicting accounts of what he wore on the day of the execution, the museum has a stained waistcoat whose material and style indicate it is of the correct date and quality to have been owned by the King. His attendant, Sir Thomas Herbert, reported that the King wore an extra shirt on the morning he was beheaded in order not to shiver in the cold January air. He didn’t want people to think he was afraid, declaring, “I fear not Death!”

Made from silk, this finely knitted undergarment (or ‘waistcoat’, as it was called at the time) was a warm, luxurious and expensive item, fit for a king. When the museum acquired the garment in 1924, the accompanying note claimed that “from the Scaffold [it] came into the Hands of Doctor Hobbs, his physician who attended him upon that Occasion”.

A 300-year-old bed sheet embroidered with a beloved’s hair

While many collected objects painted with King Charles I’s portrait as tokens, there were other mementos that were very personal, such as the bedsheet intricately decorated and painstakingly embroidered by Anna Maria Radclyffe in memory of her husband, the 26-year-old Jacobite rebel James Radclyffe, the Earl of Derwentwater.

Executed for treason in 1716, Anna, kept a bed sheet that he had used while a prisoner. She embroidered the sheet as a way of dealing with her grief and stitched the lettering using human hair. The wording reads: “The sheet off my dear, dear Lord’s bed in the wretched Tower of London, February 1716, Ann C of Derwent-Waters”.

The hair used may have been her own or her husband’s, or possibly from both of them, as analysis indicates both a fairer and darker hair being used (portraits indicate that her hair was much darker than his). Until January 1716, Anna Maria was allowed to share her husband’s quarters in the Tower and she may have cut locks.

This is just one of the “many personal stories associated with the impact of public execution on the lives of Londoners over centuries”. These objects from the museum’s collection tell a more complex and nuanced history of public executions in London – “a city that witnessed the brutal death of so many, from ordinary Londoners to some of history’s most high profile cases”.

Shruti Chakraborty is Digital Editor, Content at London Museum. This article contains edited excerpts from ‘Executions: 700 years of public executions in London’, written by Thomas Ardill, Meriel Jeater, Beverley Cook and edited by Jackie Keily. The objects mentioned here were on display during the 2022–2023 Executions exhibition at London Museum Docklands.

Explore the Executions online audio tour, which tells the fascinating stories behind some of the objects in our 2022–2023 exhibition. The tour is a story of the executed, the Londoners who witnessed their deaths and the impact of public executions on the capital’s landscape, economy and society.