15 October 2024 — By Harriet Sweet-Escott, Mariarosa Spanu

Lauderdale House: Witchcraft relics hidden in the wall

Imagine finding a 17th-century wicker basket of centuries-old secrets behind your wall. At Lauderdale House, that’s exactly what happened. Odd shoes, broken glass and desiccated chickens – was it a curse or a homeowner’s protection?

This page contains content some people may consider sensitive, or find offensive or disturbing. Understand more about how we manage sensitive content.

During reconstruction work after a fire in 1963, a wicker basket of peculiar objects was discovered at Lauderdale House in Highgate, London. Hidden behind a bricked-up wall, near the first-floor fireplace, the basket included two odd shoes, one of which has been dated to 1650, a strip of plaited rush, a broken ceramic candlestick, a broken tazza (a type of shallow cup), and the desiccated bodies of four chickens.

Now part of London Museum’s collection, we probe into the significance of these curious hidden objects, and what this can tell us about the individuals who placed them here.

A reproduction of how the objects were found inside the wall at Lauderdale House.

Witchcraft or counter-witchcraft?

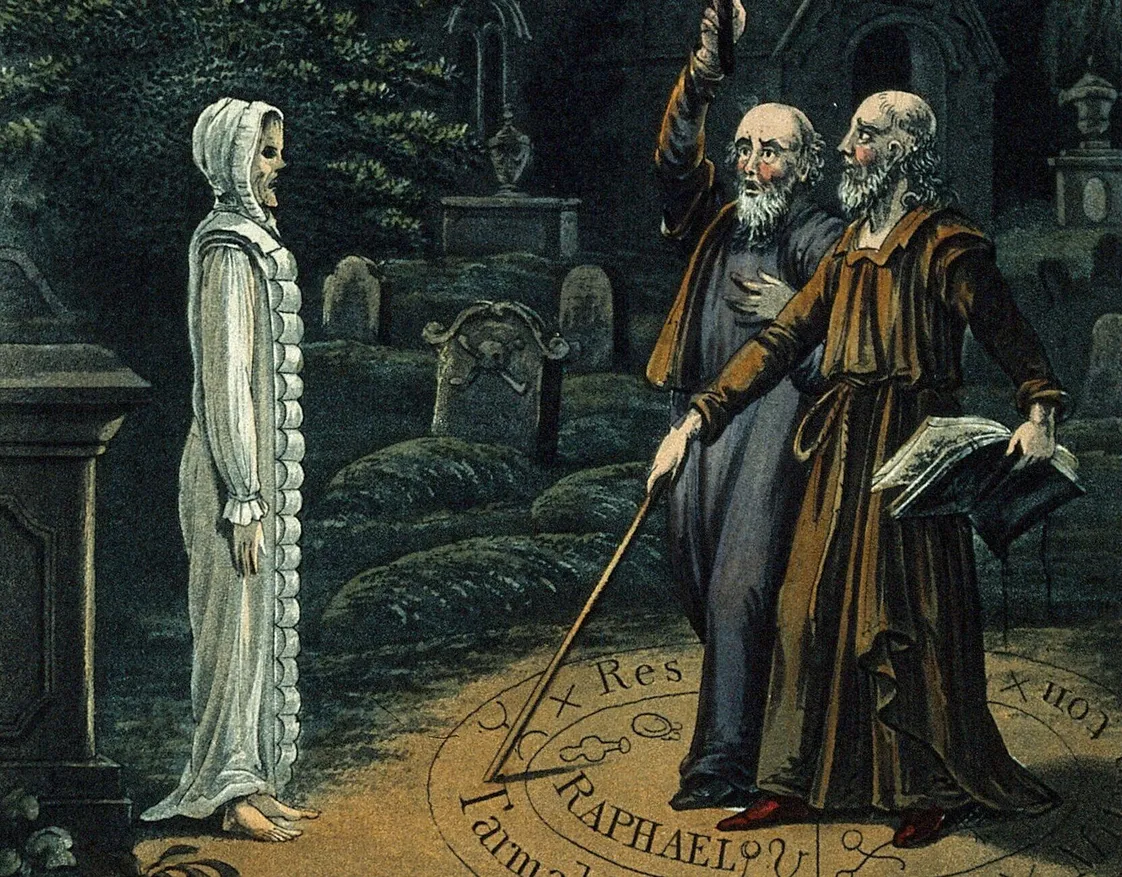

To examine these objects found at Lauderdale House, now an arts and education centre, it’s important to remember the cultural environment in post-medieval London. The objects were concealed at a time of widespread belief in magic, folklore and witchcraft.

“These objects testify to people’s acute fears towards witchcraft and other supernatural dangers. They are the actual counter-spells which were created in an everyday battle with perceived forces of evil which, it was believed, existed all around them,” writes researcher Brian Hoggard in Magical House Protection: The Archaeology of Counter-Witchcraft (2019).

Such a practice was also risky as the Church condemned them as sacrilegious, and we have evidence of people being prosecuted as wizards or witches.

The practice of hiding objects

Magical protection through hidden objects dates back to medieval times, peaking in Britain from the 17th century onwards. These ritual deposits were typically placed near fireplaces, walls, roofs, floors, and ‘openings’ like chimneys, windows or doors – areas believed vulnerable to negative forces. Evidence of this practice persisted into the 20th century.

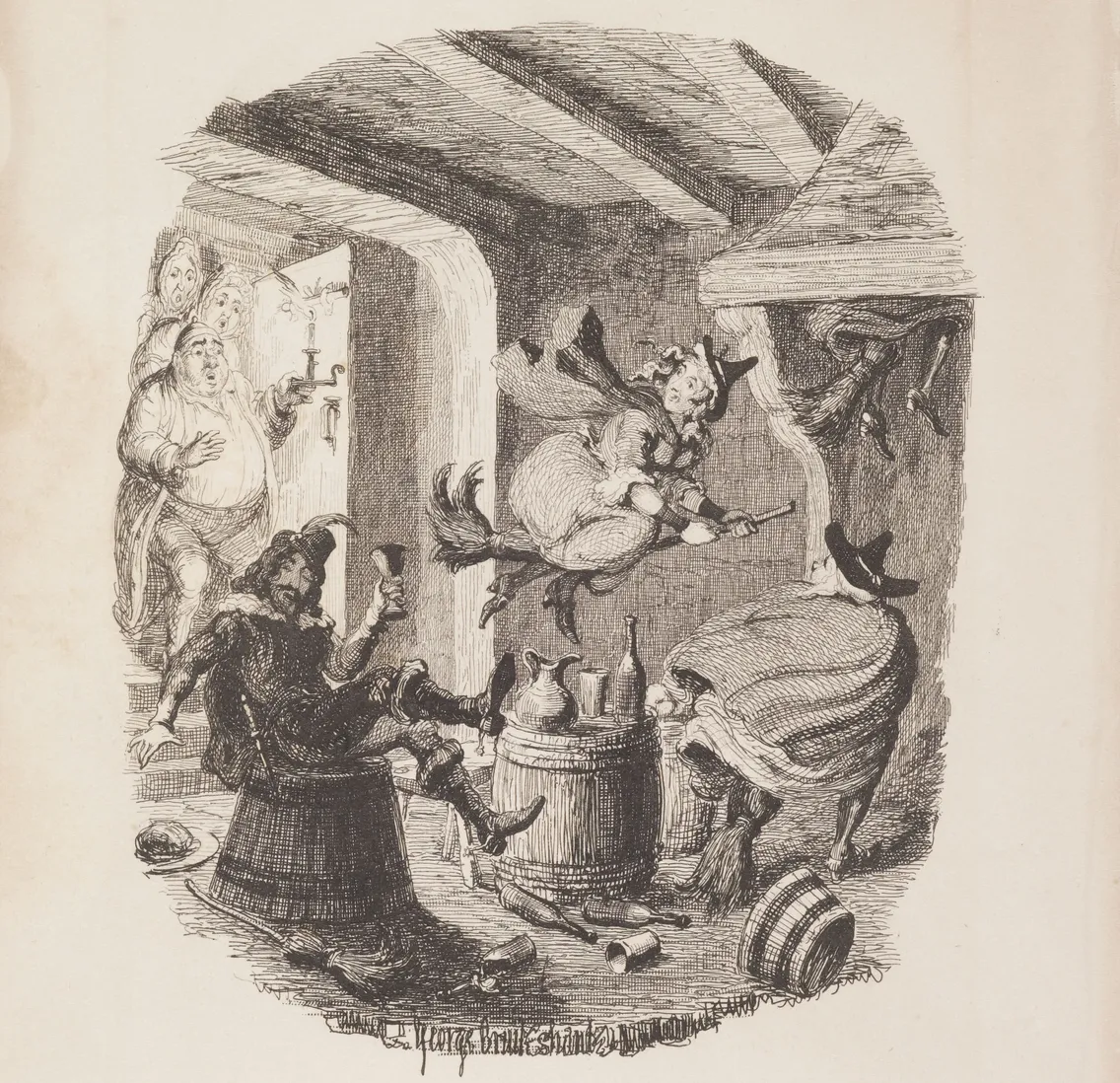

For instance, it was a widespread fear that witches would fly up or down chimneys on their broomsticks, casting malicious spells – inspiring many stories and symbolisms we come across even today, especially around Halloween.

The actual act of concealing objects could have been carried out by families and builders alike.

Hidden object rituals strengthened family bonds and house spirits, often coinciding with life events or property transfers. This practice, evidenced by the finds at Lauderdale House, was often aimed to repel, trap or confuse ‘evil’ entities like demons, spirits and witches.

Builders strategically placed objects during construction or renovations, and homeowners/occupants often seized the opportunity to add layers of protection. And some sought help from ‘cunning folks’ (as magic practitioners were sometimes called) for enhanced effectiveness.

Odd shoes found at Lauderdale House

So, what of the objects found at Lauderdale House? While seemingly unrelated, each could carry a specific meaning in terms of house protection and folk magic.

The first objects we look at are two single shoes. Often well-worn, these are the most common concealed objects – occasionally found in pairs – from post-medieval times. Their unique shape, moulded to the wearer’s foot, was thought to represent the individual intimately. Hoggard suggests these shoes acted as decoys, luring malevolent forces into a trap among other broken objects’ sharp edges.

Ralph Merrifield, archaeologist and former curator at London Museum, suggests this belief in trapping evil influences in shoes may have come from a folklore associated with John Schorn. One of England’s 14th-century unofficial folk saints, the legend of John Schorn famously capturing the devil in his boot became popular after he died in 1313. This even inspired a popular pilgrimage route until the 16th century. Our collection has a few surviving pilgrim badges that depict him trapping the devil in his boot.

A pilgrim badge from the shrine of John Schorn.

Merrifield also suggests a simpler reason for hiding shoes: bereaved relatives preserving a connection with the spirit of their departed loved ones. The theory seems plausible as most concealed shoes belonged to children, who faced high mortality rates. These hidden items may have served as spiritual links rather than protective charms.

Of concealed shoes and other objects

That shoes are a popular concealed object is further proven via the “Concealed Shoes Index” created by the Northampton Museum in the 1950s. This was based on finds that the community brought to the museum for assessment or donation. The oldest shoe in the index dates back to 1308 when the choir stalls of the Winchester Cathedral were built. The shoe was likely hidden there. Not limited to shoes, the ‘Concealed and Revealed’ project has a collaborative map of similar finds on Historypin.

Broken objects and ‘ritual killing’

Alongside the shoes, a few broken objects were also found behind the wall at Lauderdale House. This includes a broken ceramic candlestick and a broken glass tazza. While we can’t ascertain why these specific objects were concealed, perhaps the significance lies in the fact that they were broken.

As Hoggard suggests, it could have been believed that the sharp edges on broken objects would be harmful to dangerous entities, and could be used as a trap.

Maybe they were deliberately broken for this?

“The significance is not as much in the kind of object, as much as in them being ‘ritually killed’”

Their significance may not lie in the objects themselves, but in their deliberate ‘ritual killing’ and careful arrangement together. Breaking the items was believed to unlock their protective potential through a symbolic transition from a ‘whole’ state to another.

The plaited rush – knot magic or simple matting?

Evidence of ‘knot magic’?

Alongside the shoes and broken objects was a long strip of plaited rush. Author Della Farrant, who has researched this collection from Lauderdale House, writes that while initially appearing as common domestic magic, closer inspection suggests the plaited rush is an example of ritualistic magic, specifically “knot magic”. This is further emphasised by the dead chickens and “the apparent presence of a chalice”, ie, the glass tazza.

Knot magic is a form of witchcraft in which the type of knots can symbolise varying intentions and is often used in protection spells. Could our plaited rush piece be evidence of knot magic? Or, perhaps, simply the remains of a weaved rush matting for the chickens?

There were chickens, not cats

The most disturbing components of this collection from Lauderdale House are four desiccated chickens – two strangled to death, and two possibly walled in alive (a fact we could infer from the remains of an egg that was laid after the wall was sealed).

Interestingly, concealing chickens isn’t as common in Britain as in the rest of Europe. Desiccated cats, and we have a few in our collection, are commonly found in house foundations and inside walls as they were used to keep rodents at bay. But why chickens?

“What curious objects might still be concealed in walls?”

Chickens are considered protective in many cultures, with their claws used against the evil eye. In Spain, desiccated chickens have been found in public buildings like churches and city walls, some dating back to medieval times.

In central European folklore, roosters’ crow was believed to repel the devil. A possible reason for concealing chickens, maybe?

What remains hidden?

Hidden within buildings worldwide, material evidence of ritual and practical magic against supernatural dangers awaits discovery. These objects, including witch bottles, charms and curses (several examples of which exist in our collection), offer insights into Londoners’ fears and beliefs over centuries.

The subject's enduring intrigue makes us wonder: What curious objects might still be concealed in walls? If found, would you leave them be or add to it?

Harriet Sweet-Escott and Mariarosa Spanu are Project Assistants (New Museum) at London Museum.